In the early months of 2020, the Fed aggressively flooded the system with liquidity, meeting three times in March alone. That was the need of the hour. Now, it probably needs to act with a similar speed – only in the other direction. A 50-basis-point hike in March will provide a shock and awe and will telegraph to the markets that it is determined to prick the inflation bubble.

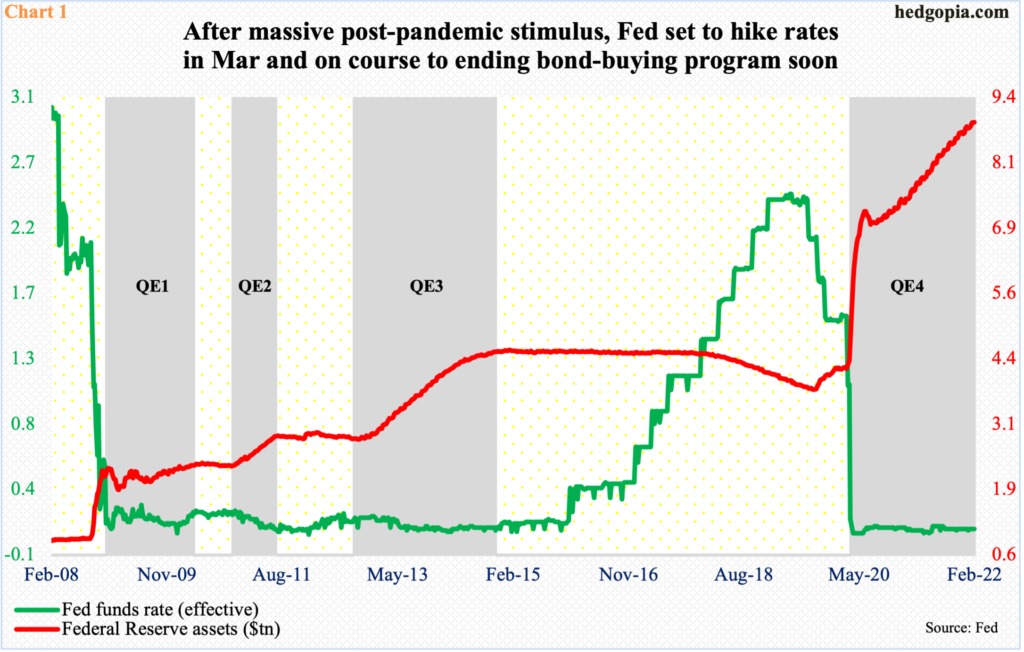

In March 2020, as Covid-19 began to swiftly disrupt the global economy, the Federal Reserve got into action. The fed funds rate, which beginning July 2019 was already being lowered from a range of 225 basis points to 250 basis points, was in a range of 150 basis points to 175 basis points when 2020 began, and the central bank held $4.15 trillion in assets.

The FOMC meets eight times a year, but can have unscheduled meetings, if warranted. In 2020, the first scheduled meeting was held on January 28-29. The second was on dock for March 17-18. By then, the virus was creating havoc. Sensing the immediacy of the situation, the Fed decided not to wait until the scheduled meeting.

On March 3, the fed funds rate was lowered by 50 basis points to a range of 100 basis points to 125 basis points, and by a full percentage point on the 15th to a range of zero to 25 basis points (Chart 1). The scheduled March 17-18 meeting was cancelled, but the Fed assembled again on the 23rd. Besides, there were two announcements in that month – relating to a temporary dollar liquidity arrangement with other central banks on the 19th and a temporary repurchase agreement facility for foreign and international monetary authorities on the 31st.

The March 23rd gathering was a special one, as it was in that meeting that the Fed essentially announced an open-ended quantitative easing (QE). The S&P 500 large cap index, which crashed 35.4 percent intraday in five weeks, bottomed on that very day at 2192. On January 4 (this year), it ticked 4819 before coming under pressure. Federal Reserve assets, in the meantime, have ballooned to $8.87 trillion.

In 2020, the Fed needed to show the urgency it showed and deserves kudos for that. Things globally were falling apart.

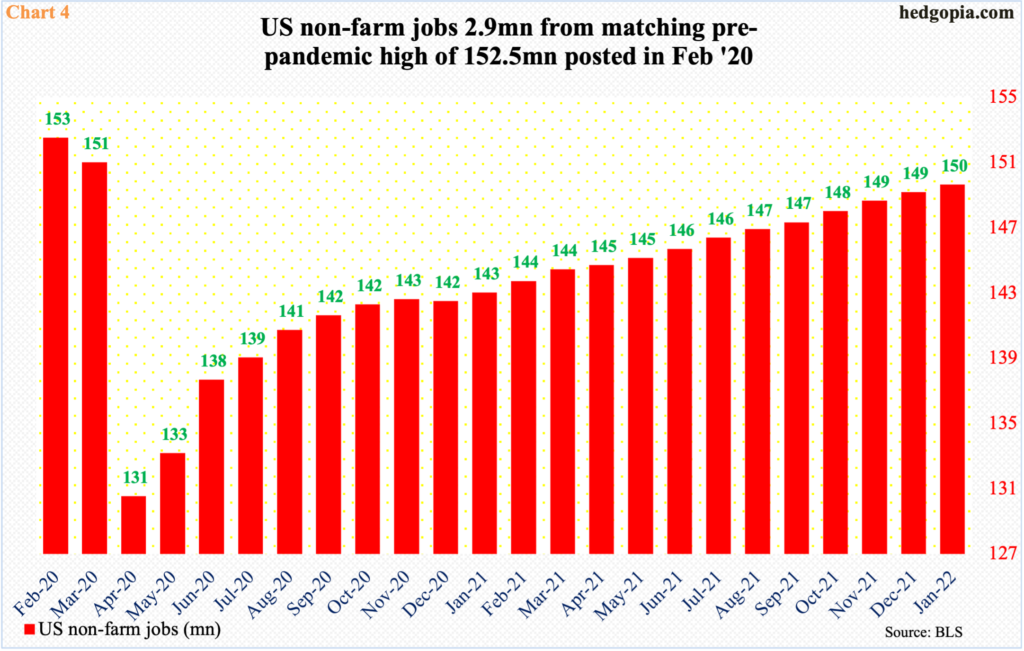

In the US, within a couple of months from February to April, non-farm jobs collapsed from 152.5 million to 130.5 million (Chart 4).

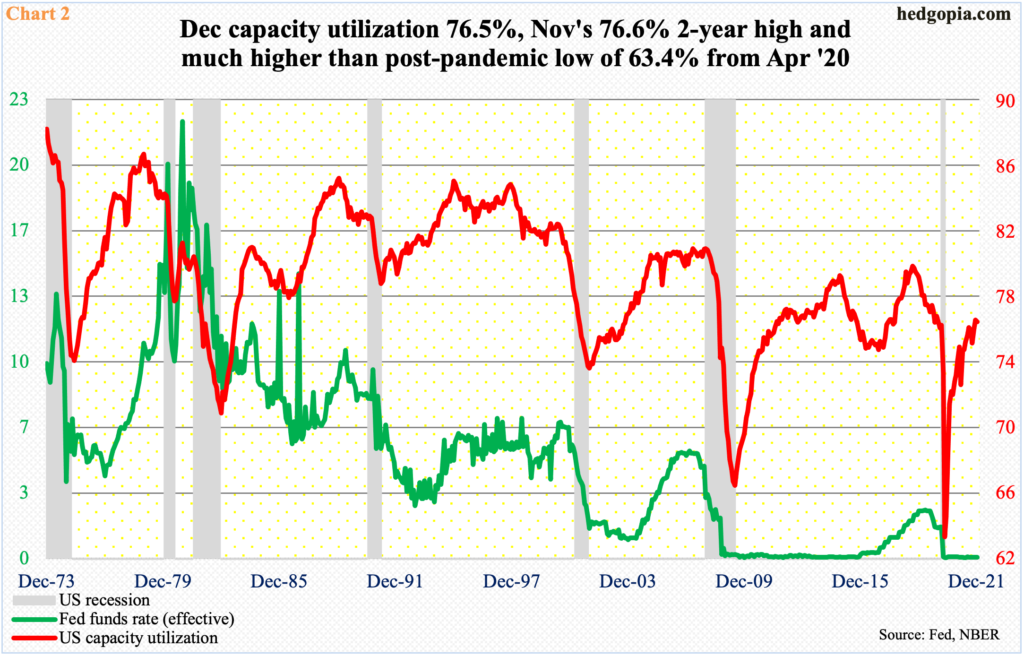

The US capacity utilization rate went from 76.3 percent to 63.4 percent between those two months. Incidentally, directionally at least, utilization and the benchmark interest rate tend to move together. That has not been the case in this cycle, or for over a decade for that matter (Chart 2).

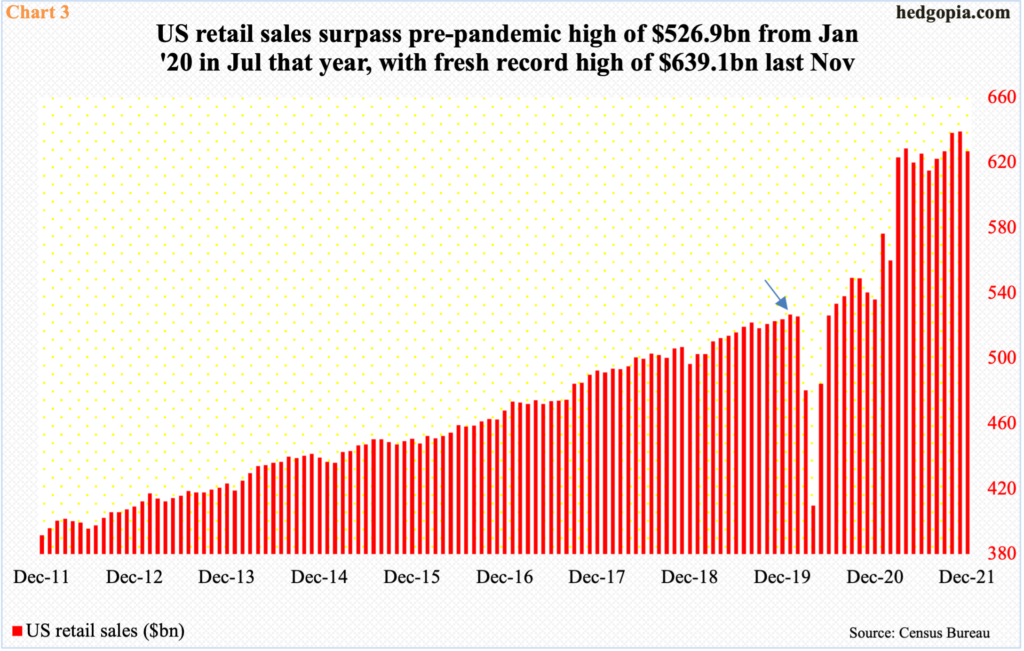

Along the same lines, US retail sales hit $526.9 billion in January 2020. By April that year, they were languishing at $409.8 billion.

Fast forward to now, things have turned around – substantially – with several data points surpassing the pre-pandemic highs.

Retail sales exceeded the January 2020 high (arrow in Chart 3) in July that year and never looked back. By last November, a new high of $639.1 billion was posted, with December down 1.9 percent month-over-month to $626.8 billion.

GDP similarly is at a new high. In 2Q20, nominal and real GDP dropped to $19.5 trillion and $17.3 trillion respectively. By 4Q21, they respectively hit $24 trillion and $19.8 trillion – both fresh records.

In spite of that, the monetary policy remains stimulative.

Until not too long ago, the Fed purchased $120 billion a month in mortgage-backed securities and treasury bonds. It is still buying but at a significantly reduced pace and is on pace to soon wind down the program. Concurrently, at the end of a two-day FOMC meeting on January 26 – the first this year – Chair Powell sent strong hints that a hike was imminent in March (15-16). This is still five weeks away.

Importantly, the shock-and-awe policy of March 2020 worked. But it is also possible to overstay one’s welcome. The system in all probability is at that point right now. Once again, a shock and awe is needed– only in the other direction.

The Fed operates under a dual mandate of maximum employment and price stability. For most of 2020 and 2021, it solely focused on its jobs mandate. From down 22 million from the February 2020 peak to only down 2.9 million now, non-farm payrolls have come a long way (Chart 4). The side effects of all this recovery/stimulus have been rampant inflation.

In the 12 months to December, on a core basis, the CPI (consumer price index) and PCE (personal consumption expenditures) respectively jumped 5.5 percent and 4.9 percent. This was the steepest price rise since February 1991 and September 1983, in that order. As recently as last February, the two were growing at a subdued 1.3 percent and 1.5 percent rate, before going parabolic (Chart 5).

Central bankers, as well as the markets, like to focus on core inflation, but consumers cannot similarly ignore the rise in food and energy prices, particularly if the pace of inflation is persisting, which is the case now. In the 12 months to December, headline CPI and PCE respectively surged seven percent and 5.8 percent, in that order. Once again, this was the highest price increase since June 1982.

There are early signs price inflation is beginning to seep into the system.

January’s jobs report was published last Friday; the economy produced much-better-than-expected 467,000 non-farm jobs, with December seeing a sharp upward revision. Alarmingly for central bankers, average hourly earnings in January jumped 5.7 percent year-over-year; last April, the metric edged up 0.6 percent.

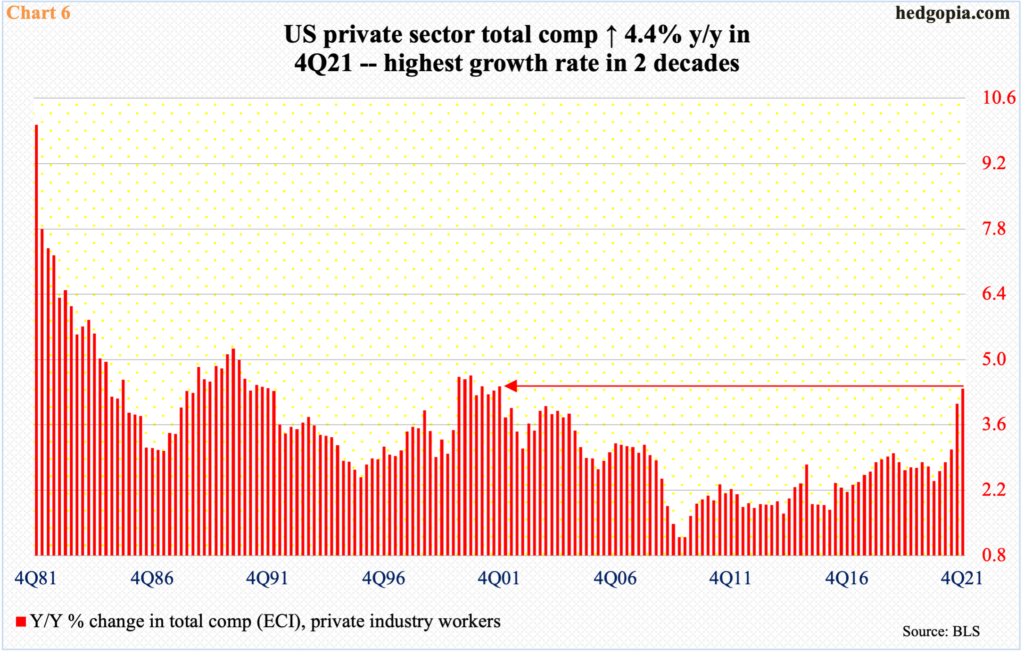

The employment cost index, which includes both benefits and wages & salaries, captures the trend even better. In 4Q21, private-sector total compensation increased 4.4 percent y/y. This was the highest growth rate in two decades (Chart 6).

Wage increases are being built into long-term contracts. Once this takes roots, it will be hard to control. Employees are demanding higher wages expecting price inflation to continue, and employers are obliging. The trend was let loose by the Fed and the sooner the genie is pushed back into the bottle the better. For that, both the employers and employees need to realize that the Fed is determined to prick the inflation bubble. Similar to the early months of 2020, a shock and awe is the need of the hour.

The Fed will have their intention known by either moving ahead of the scheduled March meeting or raise by 50 basis points in March. In the futures market, traders currently expect up to five 25-basis-point hikes this year, including one in the upcoming meeting in March; but the odds of a 50-basis-point hike in March are only 14 percent. This is an opportunity for the Fed to provide a shock and awe. A 50-basis-point hike can do that.

Thanks for reading!