- Government’s various measures of inflation continue to elude Fed’s 2% target

- U.S. banks’ excess reserves have followed QE higher, and are sitting idle

- By paying interest on reserves, Fed encourages banks to sit on them

The Federal Reserve wants inflation. It is focused on achieving its target of two percent, but not getting it. Despite six years of zero interest-rate policy and three iterations of QE, the government’s various inflation measures continue to show subdued inflation.

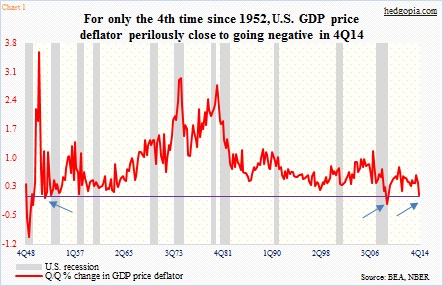

In 4Q14, the GDP deflator barely grew, up 0.04 percent sequentially, a hair’s breadth away from going negative (Chart 1). Since 1952, there have been only three occasions this series has achieved that feat – 1Q52 (-0.04 percent), 2Q09 (-0.17 percent) and 3Q09 (-0.02 percent). A drop into the minus column is quite rare.

Various other measures of inflation are not as suppressed, but they convey the same message – that there is not much inflationary pressure out there. Here is how they stacked up in the latest reporting period:

CPI (March): ↑ 0.2 percent m/m and ↓ 0.1 percent y/y

Core CPI (March): ↑ 0.2 percent m/m and ↑ 1.8 percent y/y

PCE deflator (February): ↑ 0.2 percent m/m and ↑ 0.3 percent y/y

Core PCE deflator (February): ↑ 0.1 percent and ↑ 1.4 percent y/y

PPI (March): ↑ 0.2 percent m/m and ↓ 0.8 percent y/y

Core PPI (March): ↑ 0.2 percent m/m and ↑ 0.9 percent y/y

Core CPI is growing a bit faster than core PCE deflator, but it is the latter the Fed cites in its communications, hence deserves the most attention. The last time core PCE deflator grew at two percent annually was April 2012. It has been a long time.

Inflation obviously is one of the constant themes that FOMC members talk about in speeches, hinting that if their forecast of inflation, and of course employment, fails to materialize, they will hold off on rate hiking plans.

But is the Fed doing all it can to stimulate inflation to its desired level?

Back in 2006, Congress authorized the Fed to begin paying interest on reserves held against certain types of deposit liabilities. The law was supposed to go into effect in October 2011. Then the financial crisis hit. That effective date was moved up. On October 6, 2008, the Fed announced it will begin to pay interest on depository institutions’ required and excess reserve balances. Since January 2009, it has been paying 0.25 percent at an annual rate on these reserves.

Before the Fed began QE1 in September 2008, U.S. banks’ excess reserves totaled $2.3 billion. Then they gradually marched from the lower left to the upper right (Chart 2). Now they total $2.7 trillion, and are sitting there, earning 25 bps.

Hence the dichotomy.

The Fed wants inflation, yet interest-on-reserves encourages banks to sit on them.

How would they respond if the Fed at least reduced the interest rate? We would not know until the Fed actually adopts such a policy. For reference, since the middle of last year the ECB has been charging banks to hold reserves.

There is no guarantee that U.S. banks will oblige and open the loan spigot. There probably is not enough demand out there to begin with. Even worse, the new funds may simply find their way into creating more asset inflation.

Nonetheless it is a tool that the Fed has at its disposal but remains untested.