Consumer credit is at a record high, including auto loans. Already stretched, consumers are now having to deal with higher rates. Evidently, consumer sentiment remains suppressed. This has the potential to seriously impact retail sales next year – negatively, of course.

Consumer credit hit a new high in October, up 3.1 percent from a year ago to a seasonally adjusted $4.99 trillion. This is made up of $1.3 trillion in revolving (credit cards, etc.) and $3.69 trillion in non-revolving (home mortgage, etc.) – up 9.3 percent and one percent year-over-year respectively.

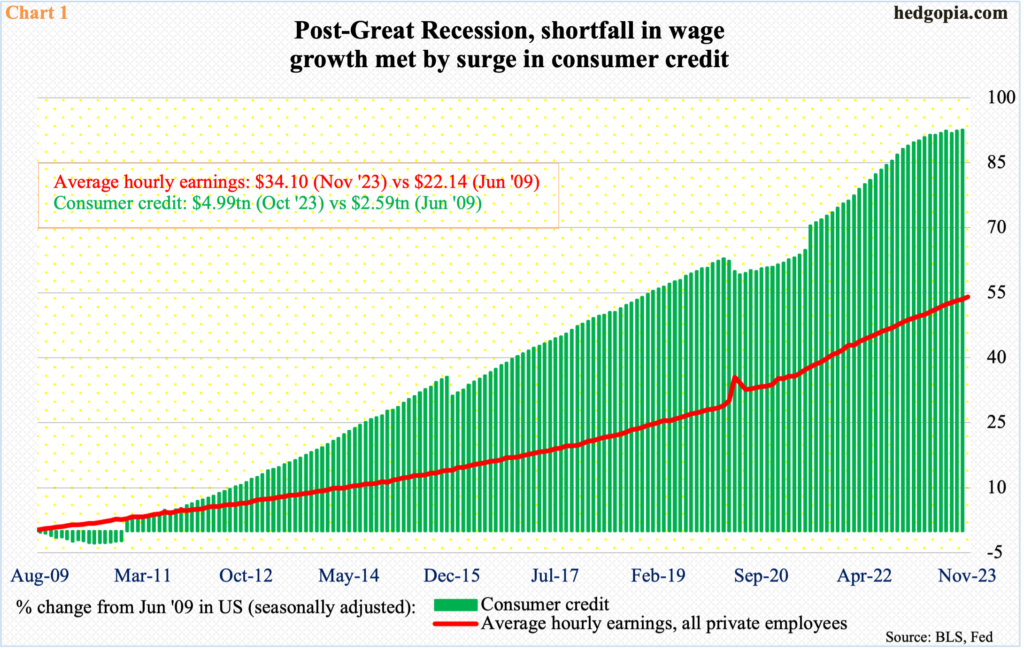

Americans’ fascination with credit goes back decades. This is being used to maintain living standards beyond which is allowed by wage growth. In the post-Great Recession era, for instance, non-farm average hourly earnings went from $22.14 in June 2009 to $34.10 in November this year, for cumulative growth of 54 percent; in the meantime, consumer credit jumped 92.6 percent from $2.59 trillion in June 2009 to October’s fresh record (Chart 1).

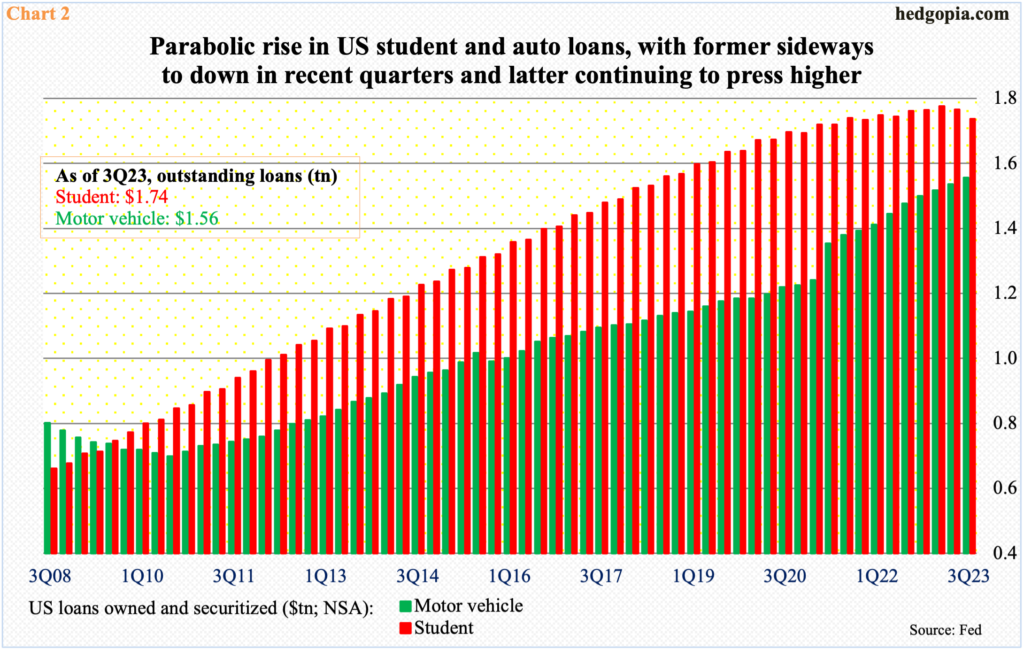

Auto and student loans make up a big chunk of this growth. As of 3Q23, they respectively stood at $1.56 trillion and $1.74 trillion. Over the years, student loans have grown much faster, as this category totaled $481 billion in 1Q06, versus $782 billion for auto loans.

In recent quarters, though, student loans are sideways to slightly down, having peaked at $1.77 trillion in 1Q23. Auto loans, however, continue to trend higher (Chart 2). This at a time when interest rates have meaningfully risen.

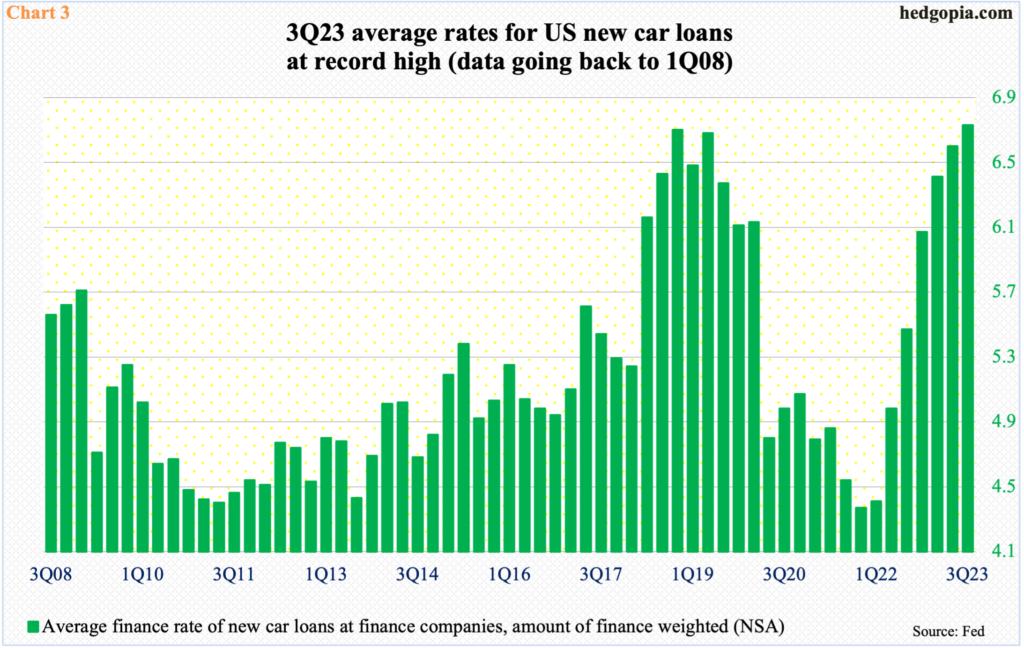

The fed funds rate currently stands at a range of 525 basis points to 550 basis points, up from zero to 25 basis points in March last year when the Federal Reserve began to tighten its monetary policy.

In 4Q21, just before the central bank began hiking, the average rate of new car loans was 4.4 percent; last quarter, this stood at 6.7 percent, which has not been this high since at least 1Q08 (Chart 3).

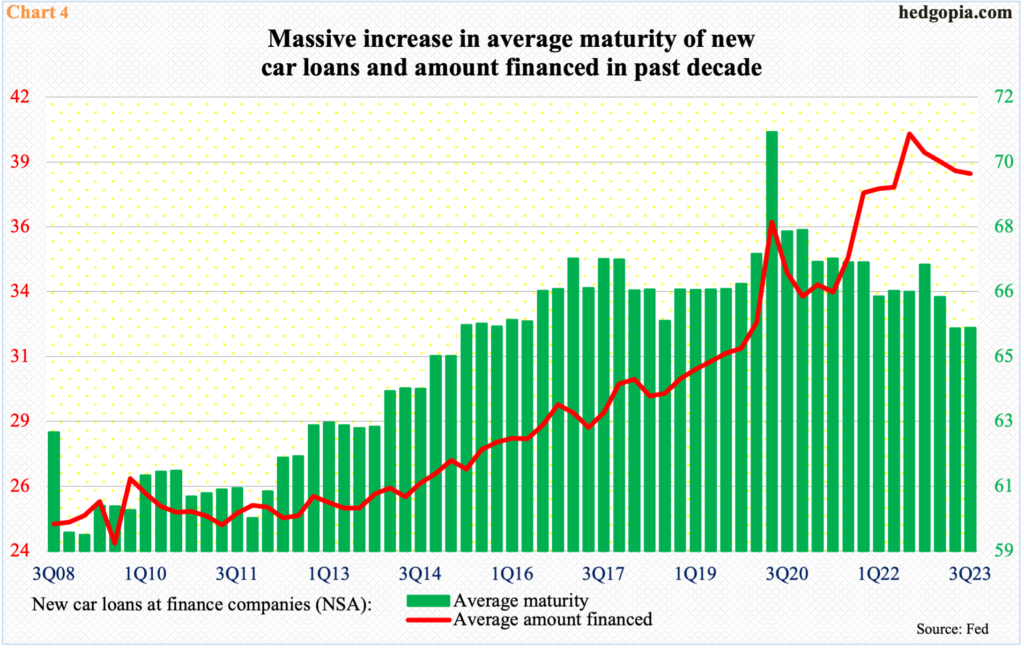

Even before the latest surge in finance rates, consumers were already forced to extend the average maturity of their loans. In 1Q09, a quarter before the end of Great Recession, the average maturity was 59.5 months. By 2Q20, as the economy was exiting the Covid-19 recession, this had shot up to 71. Last quarter, this came in at 65.4 – still much higher versus where things were a decade ago (Chart 4).

In the meantime, at $38,588, the average amount financed last quarter was slightly off the 3Q22 record of $40,156 but remains much higher than even a couple of years ago.

The bottom line is that the auto companies’ creativity is lessening the burden of monthly payment for consumers, but the fact remains that the latter is stretched – particularly so at a time when rates have risen a lot and consumer inflation, even though substantially off last year’s four-decade highs, remains elevated.

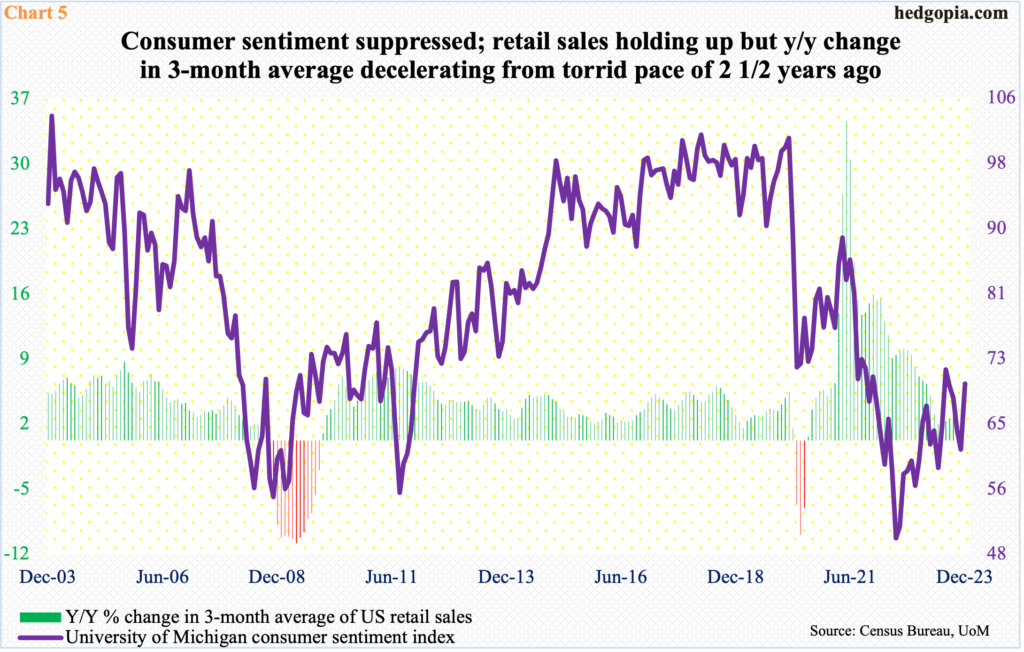

This helps suppress consumer sentiment – an oddity at a time when the overall economy is on pace to grow well north of two percent this year.

In June last year, the University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment index hit a rock bottom 50 and rose as high as 71.5 this July. Then in November it hit 61.3 before jumping 8.4 points this month to 69.7. The ongoing rally in stocks probably played a major role in uplifting the general mood. If so, sentiment is vulnerable as the exceedingly overbought equity indices begin a process of unwinding next year. Because at some point, this can get reflected in retail sales.

At an absolute level, retail sales rose to a record $705.7 billion in November. But the underlying growth is decelerating. Chart 5 calculates the y/y growth – or a lack of thereof – in three-month average of retail sales. In June, this hit as low as 1.6 percent before rising to 3.4 percent last month. This is respectable but much slower than the double-digit pace of 2021 and 2022, with growth as high as 34.9 percent in May 2021. This was clearly unsustainable, but with the current low-single-digit pace, it does not take much to push the metric into negative territory. That is the risk for next year, and the sentiment reflects that.

Thanks for reading!