As 2014 began, growth expectations were very high for the U.S. economy. In fact, every year since the recession ended mid-2009, economists’ GDP forecasts have been on the optimistic side, only to be progressively cut back as the year progresses. Interest-rate expectations are the same way. For the last several years, it has been a popular call to expect a treasury sell-off, though it has not quite panned out that way. Of course, the 10-year rose from just under 1.4 percent in July 2012 to a tad over three percent late last year, but the much-expected massive liquidation from bonds into stocks is yet to turn into a reality.

As 2014 began, growth expectations were very high for the U.S. economy. In fact, every year since the recession ended mid-2009, economists’ GDP forecasts have been on the optimistic side, only to be progressively cut back as the year progresses. Interest-rate expectations are the same way. For the last several years, it has been a popular call to expect a treasury sell-off, though it has not quite panned out that way. Of course, the 10-year rose from just under 1.4 percent in July 2012 to a tad over three percent late last year, but the much-expected massive liquidation from bonds into stocks is yet to turn into a reality.

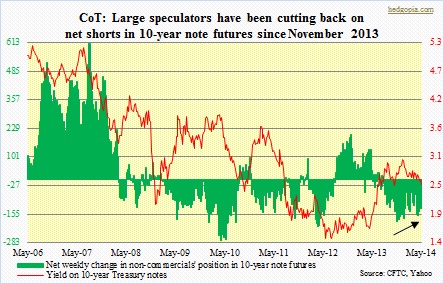

In this context, the recent breakdown in yield in the 10-year (and the 30-year) is noteworthy. Since the Fed started to taper early this year, the 10-year has dropped 50 basis points to 2.5 percent. The conventional wisdom would tell us that the taper would put downward pressure on treasuries. But it seems other buyers are showing up. We can throw all kinds of reasoning behind this – demographics being one, as an increasing number of retirees leads insurance and pension funds to go long duration.

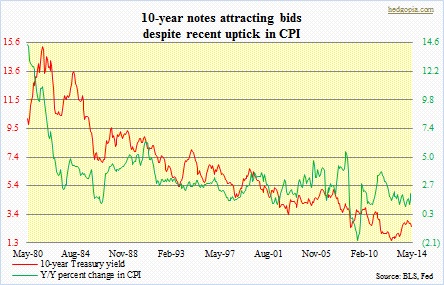

Inflation is another variable. In the big scheme of things, reported inflation is subdued, which has helped create a price floor for treasuries. Direction-wise, yields on the long end of the curve more or less follow inflation (chart on top). Recent monthly readings in the headline CPI have been picking up, and this has come at a time when treasuries are attracting bids. What gives? Does this represent a growth scare? Since the current recovery began mid-2009, annual growth has hovered around two percent, which falls well short of the historical average of 3.3 percent.

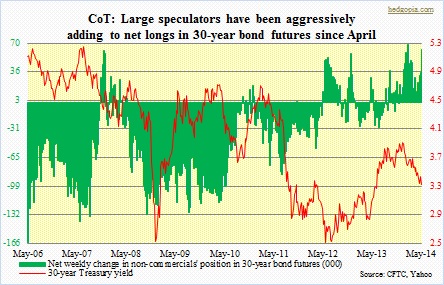

Since the publication early this month of 1Q14 advance estimate of the GDP – the 0.1 percent SAAR expansion shocked even the most pessimists – 2014 numbers have been cut back some, but the consensus expectation continues to be a vicious snap-back in 2Q14 as well as 2H14. Over at the CBOT, futures traders in 30-year bonds seem to be positioning for a different outcome. A vicious snap-back in the economy is not likely to go hand in hand with a rally in treasuries. These large speculators have been aggressively adding to net longs, with the latest reporting period representing both an increase in longs and a decrease in shorts; by the way, they have played the rally in 10-year notes since early this year perfectly.

Since the publication early this month of 1Q14 advance estimate of the GDP – the 0.1 percent SAAR expansion shocked even the most pessimists – 2014 numbers have been cut back some, but the consensus expectation continues to be a vicious snap-back in 2Q14 as well as 2H14. Over at the CBOT, futures traders in 30-year bonds seem to be positioning for a different outcome. A vicious snap-back in the economy is not likely to go hand in hand with a rally in treasuries. These large speculators have been aggressively adding to net longs, with the latest reporting period representing both an increase in longs and a decrease in shorts; by the way, they have played the rally in 10-year notes since early this year perfectly.

The message is not as clear in the 10-year. Nevertheless, these large speculators have been cutting back on their net short positions since mid-April. Technically, there has been some damage done lately in both the 10- and 30-year. Near-term, both are overbought (price), but the 10-year (yield) now faces resistance at 2.6 percent, and the 30-year is trapped in a five-month-long descending channel.