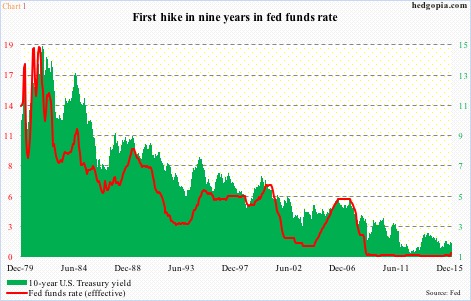

In the past couple of weeks, there have been three important developments on the central-banking front, including the first hike by the Fed in nine years (Chart 1).

It is too soon to say with conviction, but are major central banks subtly trying to convey to Mr. market that they are fast reaching the end of the stimulus rope?

Makes you wonder.

One thing we can say with conviction is that central bankers would not have it easy in the months and years to come.

In some ways, they have themselves to blame – at least the ones heading up the world’s major central banks.

Gone are the days when these bankers unassumingly went about carrying out their respective countries’ monetary policies. They have taken on rock-star status.

Ben Bernanke and his successor Janet Yellen (chair of the Federal Reserve), Mario Draghi (president of the European Central Bank), Haruhiko Kuroda (governor of the Bank of Japan), Mark Carney (governor of the Bank of England), Zhou Xiaochuan (governor of the People’s Bank of China), these have become household names.

How did they get here?

During the 2008/2009 crisis, the financial system was on the precipice of collapse. No exaggeration here. The system was fast running out of lubricants. And in a credit-based system, that is no good.

The likes of Mr. Bernanke, Mervyn King (BoE), Jean-Claude Trichet (ECB), Masaaki Shirakawa (BoJ), among others, stepped up to the plate.

In the U.S. in particular, Congress quickly passed TARP, a $800-billion bailout plan of 2008. This was further supplanted by Mr. Bernanke’s unconventional monetary policy.

Quantitative easing (QE) has since become a buzzword.

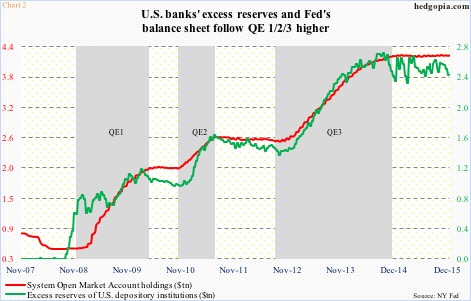

Simply put, central banks resort to QE when standard monetary policy has become ineffective. By December 2008, the fed funds rate was already pushed down to near zero. The economy needed further stimulus. The Fed began to massively expand its balance sheet to purchase mortgage-backed securities and Treasury securities.

The system did not fall apart.

This is the good side of it. The bad is that QE, to the delight of Wall Street, just kept coming – QE 1, 2 and 3 (in the U.S.). Markets had become addicted to it, and kept asking for more – and got. The Fed’s balance sheet grew from $850 billion prior to the 2008 crisis to $4.4 trillion. U.S. banks’ excess reserves grew along with it (Chart 2).

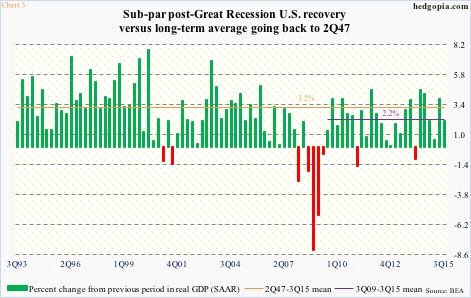

All along, the U.S. economy grew subpar, giving fodder to those questioning if QE was helping Main Street at all.

Post-Great Recession, real GDP has averaged growth of 2.2 percent, versus 3.2 percent going back to 2Q47 (Chart 3).

Central banks have mandates that they operate under. The Fed, for instance, has a dual mandate of maximum employment and price stability. Mr. Bernanke also liked to talk about the efficacy of the wealth effect, hence needed higher stock prices. QE helped.

Ditto with the BoJ, which not only printed money to buy Japanese government bonds but also exchange-traded stock funds. It currently owns a third of the JGB market, and half of the ETF market. As an exports powerhouse, a weak yen would not hurt. In the past four years, the yen has dropped 38 percent against the dollar.

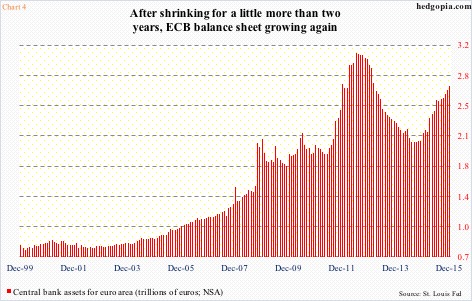

Since April 2008, the euro has lost 32 percent. The ECB says it does not target the exchange rate. They all say that. Besides gaining competitiveness, a lower euro can also help push up the region’s low inflation. Enter QE.

In November 2007, the ECB’s balance sheet stood at €1.3 trillion, peaking at €3.1 trillion in June 2012, before coming under pressure and bottoming at €2 trillion in September last year. Thanks to the ongoing QE in the Eurozone, the balance sheet has now gone up to €2.7 trillion (Chart 4).

What is the end game in all this?

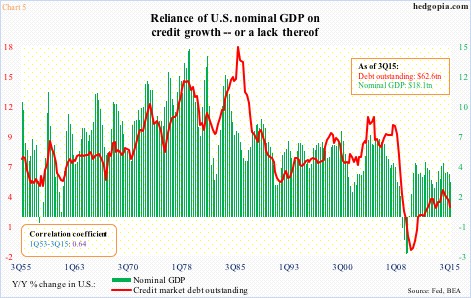

Seven years after the global crisis, it is dawning on many that central-bank activism is no panacea in and of itself. Everywhere we look, the debt pile, which was at the root of the financial crisis in the first place, has continued to go up, even as economic growth keeps coming up short. Chart 5 highlights the reliance of the U.S. economy on debt.

But are central bankers realizing this?

Three developments over the past couple of weeks are worth noticing.

In its December 3rd policy meeting, the ECB cut by minus 0.1 percent the interest rate it pays on commercial bank deposits to minus 0.3 percent and extended its €60-billion monthly bond-buying program by six months until March 2017. Markets wanted more. The euro rallied, and European stocks took it on the chin.

Last Friday, the BoJ left the overall target of annual asset purchases unchanged at around ¥80 trillion, lengthening the average maturity of the JGBs it purchases to seven to 12 years from seven to 10 years. Plus, it will buy another ¥300 billion of exchange-traded equity funds, which will be in addition to the ¥3 trillion in ETFs it has purchased annually since late 2014.

Markets were not expecting the BoJ move. Mr. Kuroda was probably trying to pull a surprise, but it worked the other way. Mr. Market gave its verdict: Not enough. The yen rallied, and the Nikkei sold off hard.

And on Wednesday last week, the Fed delivered its first rate hike in nine years, after staying zero-bound for seven long years. U.S. stocks rallied on Wednesday, but gave it all back, and then some, on Thursday and Friday.

More important, in the U.S., futures traders are pricing in two quarter-point hikes in 2016. The Fed expects four.

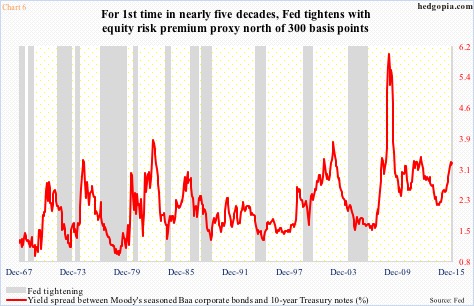

It is understandable for the Fed to be wanting to fill its monetary quiver with arrows. The U.S. economy is in its seventh year of recovery, and maturing. Hindsight is always 20/20, but the Fed had a much better window of opportunity to tighten early this year, or late last year. Now, it is having to raise in the face of equity risk premium proxy north of 300 basis points (Chart 6). This has never happened going back at least 12 tightening cycles.

This is probably why futures traders are essentially betting that in due course the Fed will be proven wrong, and that the U.S. economy is not strong enough to sustain four rate hikes next year.

Central-banking history is littered with such faux pas. In 1990, the BoJ hiked aiming to burst the equity bubble. In 2011, the ECB hiked fearing inflation that never showed up.

That said, stock markets’ addiction to monetary morphine keeps growing. At some point, it has got to stop. The question is, is it now or sometime down the line?

The Fed unwilling – or unable – to oblige markets is not a scenario stocks are currently priced for. Next year, the two are set to lock horns, with early rounds in all probability going to the latter.

The Fed, and other central banks, may be trying to keep markets on a shorter stimulus leash, but it is hard to imagine them try to break the addiction all at once.

Thanks for reading!