U.S. consumers are alive and well. There is both good and bad in this – good now but potentially bad down the road.

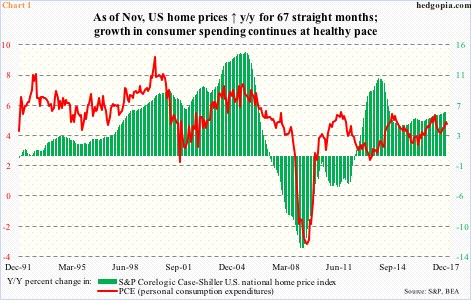

Consumer spending in December rose 0.4 percent month-over-month to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of $13.7 trillion. This followed upwardly revised 0.8-percent growth in November. Year-over-year, spending rose 4.6 percent, down from 4.7 percent in November, and has increased in the four-percent-or-higher range since September 2016.

Chart 1 pits y/y change in spending against y/y change in home prices. Nationally, the latter has risen for 67 straight months. Prices rose 6.2 percent in November – the highest since 6.3 percent in June 2014 and well ahead of inflation.

At least from the ‘wealth effect’ perspective, home-price appreciation has to be a tailwind for spending.

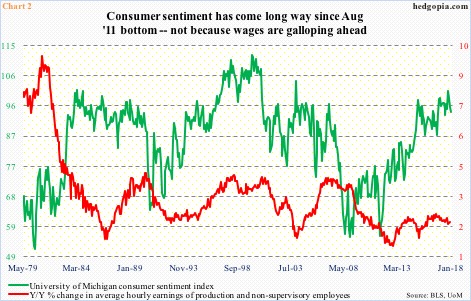

The University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment index in January fell 1.5 points m/m to 94.4, but last October’s 100.7 was the highest since 103.8 in January 2004 (Chart 2). If anything, wages are not the reason sentiment remains as elevated as it is.

Average hourly earnings of production and non-supervisory employees grew 2.3 percent y/y last December. When Great Recession ended in June 2009, they grew 2.9 percent. The red line in Chart 2 has been rising since bottoming at 1.3 percent in October 2012, but the last time it grew with a three handle was in May 2009.

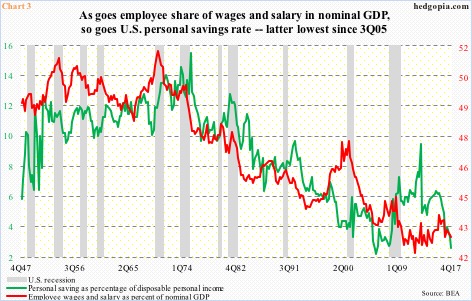

Consequently, employee wages and salary as a percentage of nominal GDP stood at a mere 42.8 percent in 4Q17. The red line in Chart 3 bottomed at 42.1 percent in 4Q11, but soon peaked at 43.9 percent in 4Q15.

To be fair, employees’ share in nominal GDP has been trending lower for nearly five decades now, as is the personal savings rate. They more or less move together, with the latter in particular very anemic.

In 4Q17, the savings rate fell seven-tenths of a percentage point quarter-over-quarter to 2.6 percent, which was the lowest since 2.2 percent in 3Q05 – in other words, back down to pre-crisis levels.

Drawing down savings to pay for growth is not a sustainable solution. Particularly if there is leverage in the system and when rates are on an upward trajectory, albeit from an artificially subdued level.

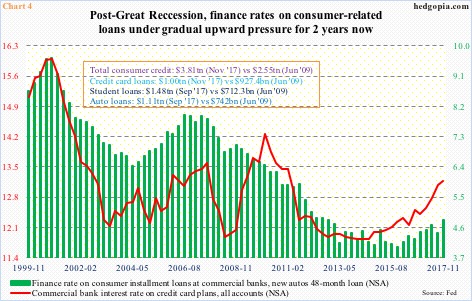

In the current recovery, consumer credit has gone up by $1.3 trillion to $3.8 trillion. Student loans are at $1.5 trillion, auto loans at $1.1 trillion, and credit-card loans at $1 trillion. And rates are on the rise.

In the past couple of years through November last year, interest rates on 48-month auto loans have risen from four percent to 4.8 percent, and credit-card loans from 12.2 percent to 13.2 percent (Chart 4).

This is all good when things are humming along. The real test is when the next downturn hits. For it increasingly feels like consumers are biting more than they can chew. This can help aggravate matters in the next recession – or even lead to one.

Thanks for reading!