- Draghi drops credible (?) hints Eurozone QE is coming

- QE no panacea for economy, only a vehicle for transfer of bond ownership

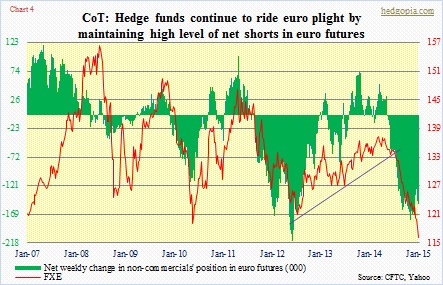

- Investor reaction post-announcement key, as net shorts in euro futures remain very high

“This may imply adjusting the size, pace and composition of the ECB’s measures. Such measures may entail the purchase of a variety of assets—one of which could be sovereign bonds.”

These were Mario Draghi’s comments in a letter dated January 6 to a European Parliament lawmaker.

There you have it. Though he has used the word ‘may’ not ‘will’, it seems QE is a sealed deal after all.

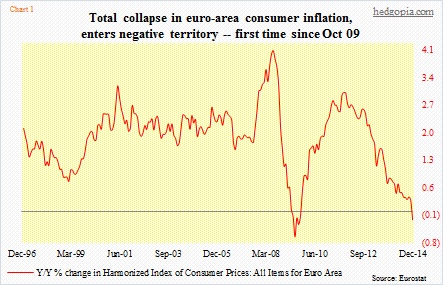

Come to think of it. Draghi had been laying the groundwork for some time. Or, one can argue he has painted himself into a corner. He has been consistently talking about the risks posed by low inflation. The ECB’s mandate is to maintain price stability within the Eurozone. (Which, by the way, is different from the Fed’s dual mandate of maximum employment and stable prices.) And this data series is not cooperating with Draghi. In a little over three years, Eurozone inflation has gone from three percent to the minus column (Chart 1). Inflation is expected to have dropped 0.2 percent in December.

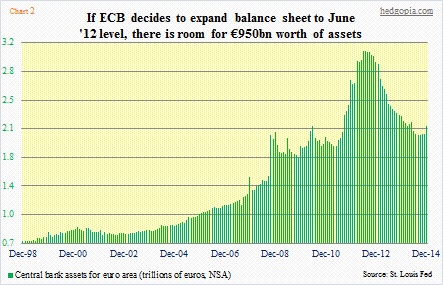

An imminent Eurozone QE on the one hand answers the ‘when’ part, on the other brings other unanswered questions into focus. How would the ECB go about doing it? How much QE is the next question obviously? For reference, ECB assets peaked in mid-2012 at €3.1tn, then began dropping, and had €2.15tn as of December last year (Chart 2). This is once again in contrast with the Fed’s balance sheet which has persistently gone from the lower left to the upper right since late 2008. There has been some talk of the ECB possibly expanding assets up to the previous peak. Should that happen, we are talking nearly €1tn.

Then the question arises, how would they go about achieving that goal? If they purchase sovereign bonds in proportion to member countries’ individual shares, then they will end up buying an inordinate amount of German bunds. Does Germany need that stimulus? Its 10-year already yields 0.51 percent. The unemployment rate, at a two-decade low, is twice that of Italy’s, where it is at a record high. The periphery is where help is needed the most. Incidentally, that is where most toxic debt lies.

QE is not a panacea. Looking at the Japan experience, as well as the U.S. to a lesser extent, QE’s efficacy in uplifting the economy as a whole is yet to be proven. Rates are already so low across the Eurozone. Yes, long-term rates have moved up in Greece, for instance, but nowhere near 2011/2012 levels (10-year currently yields 10 percent, versus in the mid-20s back then). Italy and Spain are below two percent. Imagine that. The U.S. is over two percent.

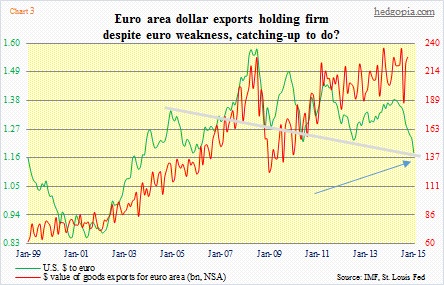

Secondly, in an environment in which end-demand is soft and the global economy tentative, currency increasingly is viewed as a tool one can fall back on. Since March, the euro has dropped 15 percent. In normal circumstances, that should have provided a huge tailwind for Eurozone exports. But there are bigger macro factors. On the one hand, China slowdown impacts German exports, on the other the likes of Italy, who are not as productive, would probably need/would like the euro to go lower still.

So far, Draghi’s jawboning has done the trick—pushing down both interest rates and the euro. Now, it is a show-me-the-money time. Eurozone bonds have attracted loads and loads of money essentially preempting the ECB move. A cynic would argue that that is what the ECB would end up achieving—a transfer of ownership of these bonds. This has been going on for a while. Greece is an example. The ECB itself owns some eight percent of Greek bonds.

From this perspective, assuming the ECB announces QE on the 22nd, the thing to watch is investor reaction. If Draghi disappoints—or is perceived to have disappointed, as a lot has already been priced in—reverberations will be felt in the currency market. Chart 4 shows the amount of net shorts built up by large speculators in euro futures. The currency has been taken to the cleaners. These traders have done a wonderful job of riding that trend. (The euro, by the way, started life on January 4, 1999 at 1.1747, pretty much where it is at currently.) These shorts potentially can be a source of reversal in the currency. Potentially is the key word here. The euro (1.1792) is at support currently (blue arrow in Chart 3). But no guarantees. Several times over the last several months, it has sliced through support zones like a knife through hot butter.