- Nice pickup in U.S. C&I loans in recent months, but…

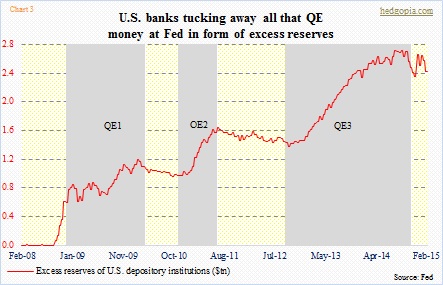

- From time QE started, banks’ excess reserves at Fed have quadrupled

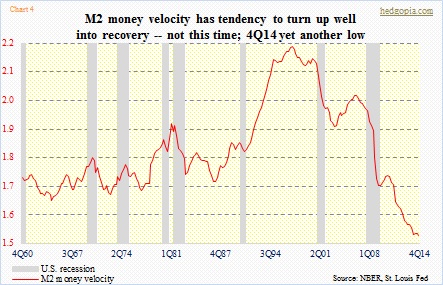

- Odds of these reserves making way into economy essentially nil as loan demand weak

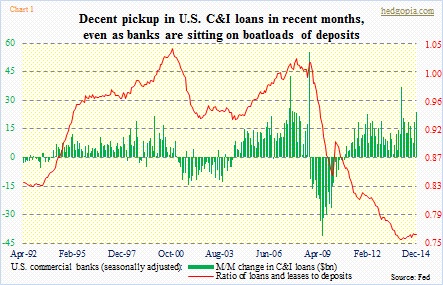

In recent months, there has been a nice pickup in U.S. commercial and industrial loans. The month-over-month change in these loans has stayed in the positive territory since November 2010, but the pace has picked up momentum over the past year or so (Chart 1). Of course this has taken place even as business inventories have swung higher, but that is another story. Just focusing on loans, the recent pickup is not only limited to C&I but overall loans, though the rate of growth is smaller in the latter.

It is also this increase in loans that has resulted in the red line in Chart 1 to begin to inch higher. That is the ratio of loans and leases to deposits. But look at the collapse since 2008 — means deposits are accumulating much faster than loans are being given out. In the big scheme of things, this is obviously not good, as, when it is all said and done, it points to one thing – there is a lack of demand for loans.

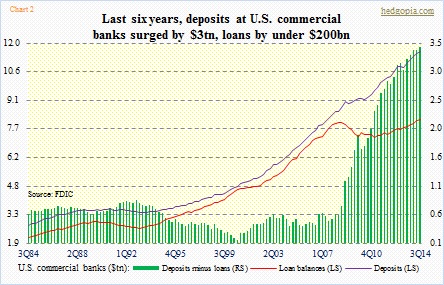

This point is driven home even better in Chart 2. Between 2Q08 and 3Q14, loan balances essentially remained flat – $8tn then and $8.2tn now. Deposits, in the meantime, expanded from $8.6tn to $11.6tn (also includes $1.4tn in foreign office deposits). Hence the parabolic rise in the green bars on the right side of Chart 2. All these deposits are sitting there earning pittance in interest. The same away banks’ excess reserves are sitting at Fed’s earning next to nothing.

The red line in Chart 3 tracks expansion in the Fed’s balance sheet. Since QE began in November 2008, System Open Market Account holdings went from under $500bn to $4.2tn when QE3 was wrapped up in October last year. Excess reserves, in the meantime, surged from around $600bn to $2.4tn now. They peaked at $2.7tn right before QE3 ended, and has been vacillating since. Nonetheless, they remain exceedingly high.

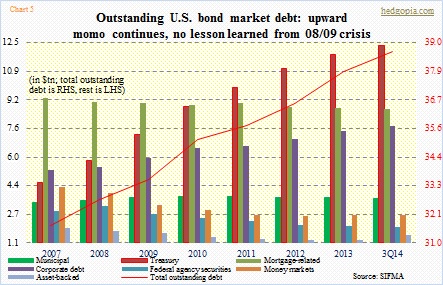

The question is, will these reserves make their way into the economy? If the answer is yes, then how would that change the inflation outlook? In some circles, it is only a matter of time before that happened. But Chart 4 presents a counterargument. The velocity of money cannot get going. In the past, after recovery gets entrenched, velocity has tended to turn up. Not this time around. Six years into recovery, we saw 4Q14 make yet another low. Therein lies the rub. The level of debt is too high in the economy. Despite all the deleveraging talk, the outstanding U.S. bond market is higher now vs. pre-Great Recession (Chart 5).

No wonder loan demand is lackluster. Sure, the recent increase in C&I loans is encouraging. But let us not get our hopes up very high.