President Trump’s tax plans could potentially impact U.S. corporate bond issuance once – and if – they become law.

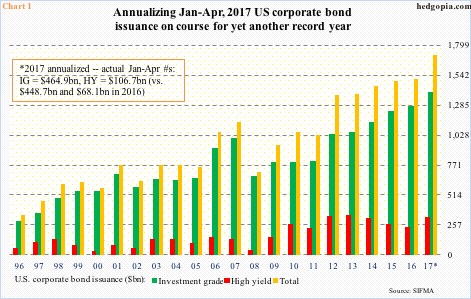

Annualizing the first four months, U.S. corporations are on pace to increasing bond issuance in double digits this year over 2016.

In 2016, issuance totaled $1.51 trillion, comprising of $1.27 trillion in investment-grade and $237 billion in high-yield. If the momentum seen in January-April holds up, issuance this year could total $1.71 trillion, made up of $1.39 trillion in investment-grade and $320 billion in high-yield.

When it is all said and done, issuance this year may or may not reach the annualized total, but, from the issuance point of view, 2017 likely is at a critical juncture.

Because of interest-rate deductibility, corporations favor debt over equity financing. Companies are allowed to deduct at least part of their interest payments against their income.

Both the Trump administration and Republicans in Congress want to cut tax rates. The latter would also like to get rid of interest-rate deductibility, even as the one-page tax plan released last week by the Administration was silent on the topic.

If deductibility is gotten rid of, that likely impacts corporate bond issuance. Even if this is left intact, a lower tax rate can reduce the attractiveness of deductions.

The Administration’s tax plan aims to cut the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 15 percent. House Republicans are gunning for 20 percent.

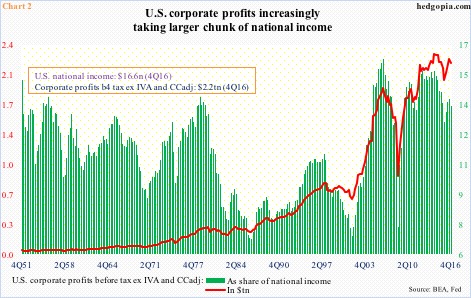

Never mind that since the turn of the century corporate profits’ share of national income has persistently risen (Chart 2). But that is a topic of another discussion.

In Chart 2, the $2.2 trillion in 4Q16 corporate profits before tax and before adjusting for inventory valuation and capital consumption is comprised of $1.28 trillion in domestic non-financial, $513.9 billion in domestic financial, and $406 billion in ‘rest of the world’.

The IRS credits a company’s U.S. tax bill for payments made overseas. Companies nonetheless have an incentive to sock away foreign profits in countries like Ireland where tax rates are much lower.

Hence the move to lower the rate. (In 1909, the top U.S. rate was one percent, which then rose all the way to 54 percent in the late ’60s, before settling at 35 percent since 1993.)

The statutory tax rate in the U.S. is 35 percent – one of the highest in the world – but the effective tax rate is much lower.

Chart 3 calculates an effective tax rate using federal taxes on corporate income as a share of corporate profits before tax and before adjusting for inventory valuation and capital consumption. The red line in the chart bottomed at 11.5 percent in 1Q09, rising to 23.9 percent in 4Q15, with 4Q16 at 21 percent.

Many U.S. multinationals pay a lower rate than the effective rate. Thus, under the new tax plan – should it become law – the tax rate needs to go a lot lower before corporations are incentivized to alter their behavior.

That said, in the event interest-rate deductibility is disallowed and bond issuance goes down, it could then reverberate through a whole host of things, not the least of which is corporate buybacks.

Thanks for reading!