Thanks to last year’s tax cuts, corporate taxes have seen a big drop, with a wide gap between what corporations make and what they pay in taxes. While this gives them more money to spend on dividends and buybacks, this also raises the risk the divergence in due course will reverberate through the economy.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 was signed into law on December 22 last year. Among other things, the US corporate tax rate was lowered from 35 percent to 21 percent. One-time repatriation of profits socked away overseas is taxed at eight percent, 15.5 percent for cash.

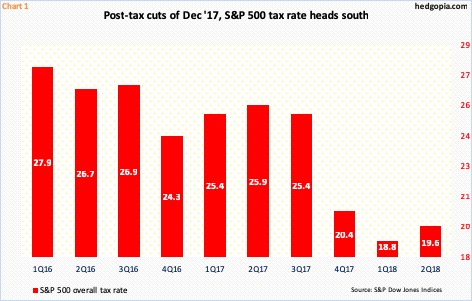

We are beginning to see the new law’s impact on corporate income statement. S&P Dow Jones Indices points out that the tax rates for S&P 500 companies in 1Q and 2Q this year are the lowest since at least 1993 (Chart 1), and that the average quarterly tax rate in 1993-2017 is 32.4 percent.

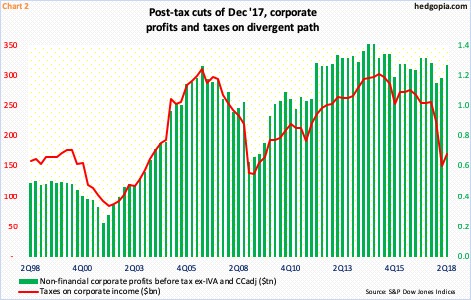

In the first half this year, the difference between what corporations earn and what they pay in taxes got much wider (Chart 2).

In 2Q, non-financial corporate profits before tax ex-IVA (inventory valuation adjustment) and CCadj (capital consumption adjustment) came in at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of $1.26 trillion. This measure of profits peaked at $1.44 trillion in 3Q14, but have been in the $1.2- to 1.3-trillion range for six years now. Corporate taxes on income, too, have been dropping since reaching a cycle high three years ago, but came under genuine pressure in 1Q and 2Q this year. The two have diverged – profits up, taxes down.

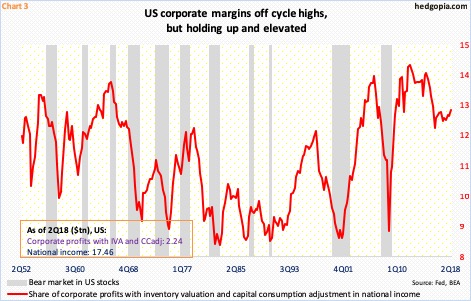

At the risk of stating the obvious, this should help drive up margins.

Chart 3 calculates the share of non-financial corporate profits adjusted for inventory valuation and capital consumption in national income. On an absolute basis, in 2Q18, they were respectively $2.24 trillion and $17.46 trillion – both new highs. In 2Q18, the margin proxy rose to 12.8 percent. This has risen since bottoming at 12.2 percent in 4Q15, with the all-time high of 14.5 percent in 1Q12. Conceivably, given the new tax regime, the red line in the chart can push higher.

For whatever it is worth, in the past, the more elevated the red line, the higher the risk of a bear market is US stocks.

Apart from capital expenditures, one of the ways corporations can part with this newfound income is by doling out more to employees. Of late, the trend in wage growth has been higher.

Average hourly earnings of private employees in October rose 3.1 percent year-over-year to $27.30. This was the first time since April 2009 that this metric grew with a three handle. That said, in the big scheme of things, wages are still suppressed, particularly considering the US economy is in its 10th year of recovery/expansion.

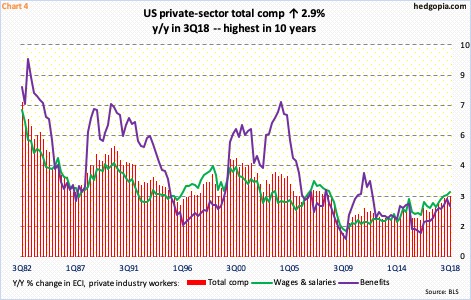

The employment cost index – another metric to measure compensation growth – shows the same trend. Total compensation – comprised of wages and salaries plus benefits – for private-industry workers bottomed at increase of 1.2 percent y/y in 4Q09. In 3Q18, it grew 2.9 percent – the fastest pace since 2Q08, but still sub-three percent (Chart 4).

Wage-push inflation is not a threat, and in all probability is not going to be anytime soon.

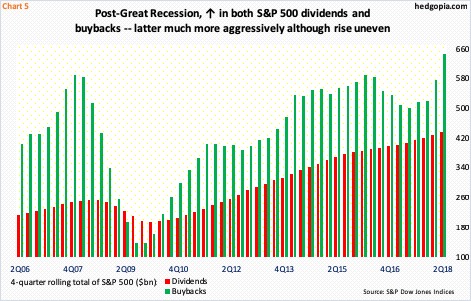

This gives corporations plenty of leeway to spend the majority of their tax windfall in dividends and buybacks. This is nothing new. S&P 500 companies have been very generous with both in the current recovery.

On a four-quarter rolling total basis, 2Q18 buybacks were $645.8 billion. On that same basis, dividends amounted to $435.7 billion – both new records.

As Chart 5 shows, there is a lot of variability in buybacks than dividends, with the latter steadily rising and the former rising but with lots of ups and downs. This is precisely what puts buybacks the most at risk. Between dividends and buybacks, corporations, if up against the wall, will choose the former. The new tax law has granted them extra flexibility, but markets anticipated this, hence the massive rally in 2017 in stocks. The struggle so far this year suggests either market participants last year had a lower corporate tax rate priced in or are doubting the sustainability of the current pace of spending. In due course, the mismatch between corporate profits and taxes can prove to be unsustainable.

Thanks for reading!