Two members of the Monetary Policy Committee, the Bank of England’s interest rate-setting committee, voted to raise interest rates by 25 basis points in August, the minutes released yesterday showed. Market participants were taken by surprise. They have been conditioned on continued flow of central-bank monetary morphine. Any news that could potentially shut off the liquidity tap is an out-of-left-field development. And so it was. Obviously the two BoE hawks are in the minority. There are seven other MPC members who have a different point of view. For now, at least. U.K. wage growth has been weak even in the midst of strong employment data, perhaps suggesting a slack in the economy. This is one of the reasons cited for keeping the rates low. Consumer inflation is well below the BoE’s two-percent target; June prices rose 1.6 percent, down from 1.9-percent increase month-over-month. Nevertheless, the hawks are ready to hike! On the surface, this is nonsensical. For five years now, U.K. interest rates have been stuck at 0.5 percent. Could it be that these hawks are beginning to worry about the harmful side effects of the extraordinarily accommodative monetary policy? The question is, will their ranks grow? Even better, should it grow?

Two members of the Monetary Policy Committee, the Bank of England’s interest rate-setting committee, voted to raise interest rates by 25 basis points in August, the minutes released yesterday showed. Market participants were taken by surprise. They have been conditioned on continued flow of central-bank monetary morphine. Any news that could potentially shut off the liquidity tap is an out-of-left-field development. And so it was. Obviously the two BoE hawks are in the minority. There are seven other MPC members who have a different point of view. For now, at least. U.K. wage growth has been weak even in the midst of strong employment data, perhaps suggesting a slack in the economy. This is one of the reasons cited for keeping the rates low. Consumer inflation is well below the BoE’s two-percent target; June prices rose 1.6 percent, down from 1.9-percent increase month-over-month. Nevertheless, the hawks are ready to hike! On the surface, this is nonsensical. For five years now, U.K. interest rates have been stuck at 0.5 percent. Could it be that these hawks are beginning to worry about the harmful side effects of the extraordinarily accommodative monetary policy? The question is, will their ranks grow? Even better, should it grow?

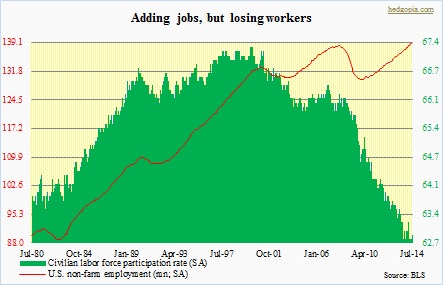

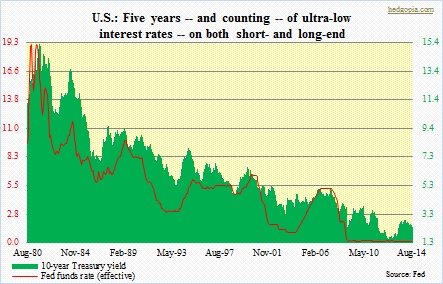

Across the Atlantic in the U.S., there are similarities. Inflation is well-behaved, wage growth is subdued, even as employment is firming (chart above). Minutes from the Fed’s late-July meeting were also released yesterday. There was just one dissenter (Philadelphia Fed President Charles Plosser). Nevertheless, Federal Open Market Committee members did discuss raising interest rates sooner, even though they continue to disagree on how much the labor market is improving. Both of these (BoE and Fed) are interesting developments. Since the financial crisis, major central banks have been in a massive accommodative mode. None has so far dared to tighten. The Fed has reduced QE from $85bn monthly to $25bn, but rates – both short- and long-term – are at/near all-time lows. Ditto with Japan. The ECB could very well be pressing on the easing accelerator, as ECB President Mario Draghi has talked about the possibility of asset purchases. The only problem is that German housing is on fire. German 10-year yields at one percent is simply too stimulative for that export powerhouse. An unintended consequence of unconventional monetary policy.

Across the Atlantic in the U.S., there are similarities. Inflation is well-behaved, wage growth is subdued, even as employment is firming (chart above). Minutes from the Fed’s late-July meeting were also released yesterday. There was just one dissenter (Philadelphia Fed President Charles Plosser). Nevertheless, Federal Open Market Committee members did discuss raising interest rates sooner, even though they continue to disagree on how much the labor market is improving. Both of these (BoE and Fed) are interesting developments. Since the financial crisis, major central banks have been in a massive accommodative mode. None has so far dared to tighten. The Fed has reduced QE from $85bn monthly to $25bn, but rates – both short- and long-term – are at/near all-time lows. Ditto with Japan. The ECB could very well be pressing on the easing accelerator, as ECB President Mario Draghi has talked about the possibility of asset purchases. The only problem is that German housing is on fire. German 10-year yields at one percent is simply too stimulative for that export powerhouse. An unintended consequence of unconventional monetary policy.

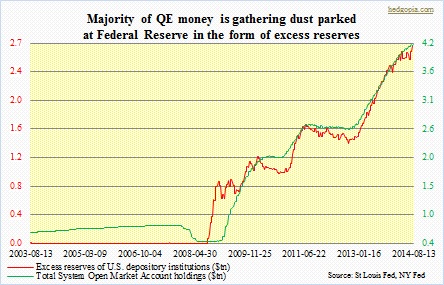

In this context, if the BoE and the Fed are preparing the markets for a rate hike, more power to them. It is wise to use the current firmness in data points – relatively speaking, of course – as an opportunity to add arrows to central-bank quivers. Currently, they are essentially empty. The sooner a return to normalcy is achieved, the better prepared these economies will be for the next downturn. And it is coming. Central banks may be adept at creating money out of thin air, but they certainly have not gotten rid of business cycles. Already, the fed funds rate may not be as straightforward a tool as in the past. Every major economy you look, liquidity is galore. There is $2.7tn in excess reserves at the Fed. U.S. banks probably will not need interbank loans as much as they did in the past. This is probably the reason why the Fed plans to use ‘interest rates on excess reserves’ as its main tool to set the fed funds rate. This relates to the rhetorical question toward the end of the first paragraph. The answer is, yes, their ranks should grow. The sooner, the better it is for the overall health of the financial system.

In this context, if the BoE and the Fed are preparing the markets for a rate hike, more power to them. It is wise to use the current firmness in data points – relatively speaking, of course – as an opportunity to add arrows to central-bank quivers. Currently, they are essentially empty. The sooner a return to normalcy is achieved, the better prepared these economies will be for the next downturn. And it is coming. Central banks may be adept at creating money out of thin air, but they certainly have not gotten rid of business cycles. Already, the fed funds rate may not be as straightforward a tool as in the past. Every major economy you look, liquidity is galore. There is $2.7tn in excess reserves at the Fed. U.S. banks probably will not need interbank loans as much as they did in the past. This is probably the reason why the Fed plans to use ‘interest rates on excess reserves’ as its main tool to set the fed funds rate. This relates to the rhetorical question toward the end of the first paragraph. The answer is, yes, their ranks should grow. The sooner, the better it is for the overall health of the financial system.