The S&P 500 closed 2020 with a new high. Momentum was very strong in November and December. In the past, more gains followed in the following year. For that, several things have to fall into place, including how flows, margin debt, foreigners and corporate buybacks behave.

The year 2020 began with a whimper and went out with a bang.

Last year, the S&P 500 opened January with a new high but only to reverse to end the month down slightly. This was then followed by a vicious February and March. By the time the large cap index bottomed at 2191.86 on March 23, it was down 32.2 percent for the year. In the next nine-plus months through the new intraday high of 3760.20 on December 31, it shot up 71.6 percent, closing at a new high of 3756.07. For the year, it was up 16.3 percent.

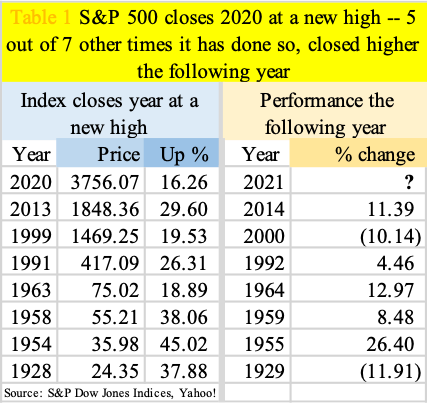

Historically, there have been seven other years in which the index closed at a new high (Table 1). In five of them, the S&P 500 went on to rally in the following year. In 1955, after a 45-percent jump in 1954, it rallied another 26.4 percent. The two down years were 2000 and 1929. Equity bulls do not obviously expect a repeat of these two years, but of how the other five ended.

Bulls should be heartened by how November and December fared, with the S&P 500 up 10.8 percent and 3.7 percent respectively. Momentum decisively shifted to a higher gear post-November 3 presidential election and particularly after Pfizer (PFE) and Moderna (MRNA) delivered positive vaccine news – on November 9 and 16 respectively.

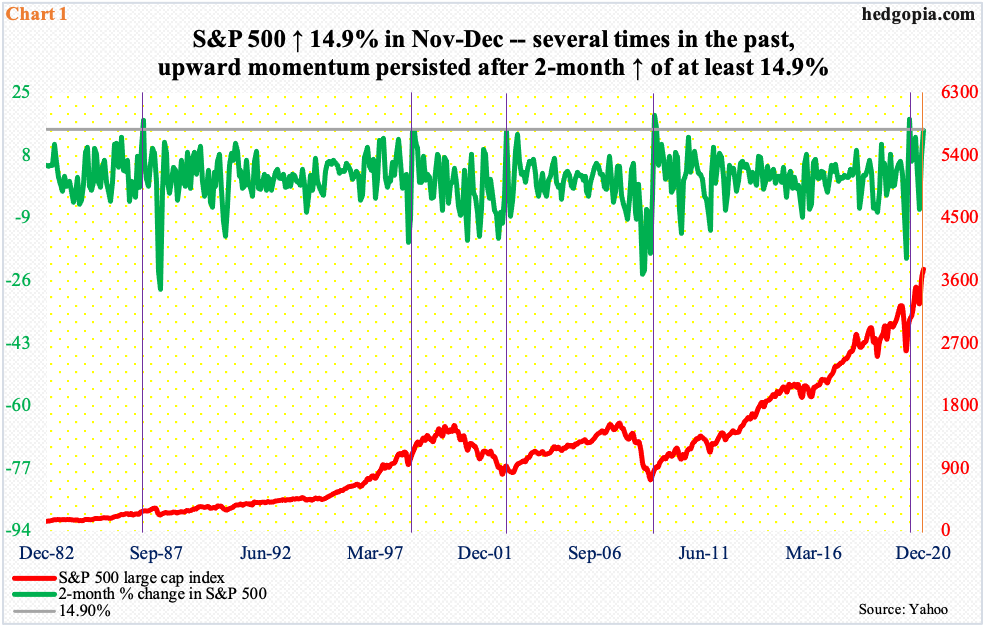

Chart 1 looks at how the S&P 500 fared after it rallied 14.9 percent over two months. Basically, the idea is to see if the two-month thrust higher carried enough momentum to push it still higher. Turns out, more often than not, momentum persists. Some of them came after major lows, including last March. As the orange vertical line shows, we just had another 14.9 percent move. So, the obvious question is, will history repeat itself?

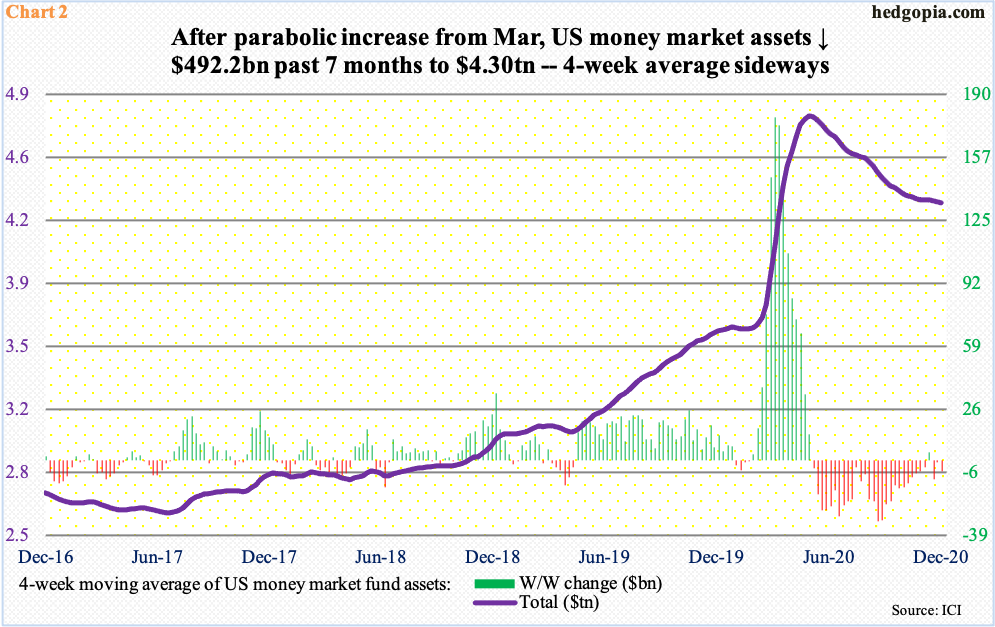

One of the things bulls are pinning high hopes on is the so-called cash-on-the-sidelines. Around the time stocks bottomed last March, US money-market assets stood at $3.9 trillion. Stocks put in a low, but these funds kept attracting money for another couple of months. By the week to May 20, there were $4.8 trillion parked in these funds. As of last Wednesday, this dropped to $4.3 trillion, down $492.2 billion from the high.

From equity bulls’ perspective, the trend is in the right direction, except for two reasons. (1) Money is moving out of these funds but are yet to meaningfully find a home in stocks. Lipper data show that from the week ended March 25 last year through last Wednesday, US-based equity funds suffered outflows of $115 billion, even as taxable bond funds, investment-grade corporate funds and high-yield funds respectively attracted $200.1 billion, $146.6 billion and $51.1 billion, among others. And (2) the seven-month trend of falling money-market assets is decelerating, which is evident in Chart 2, which uses a four-week moving average.

Bulls would prefer these assets continue their downward momentum and that stocks eventually get their fair share.

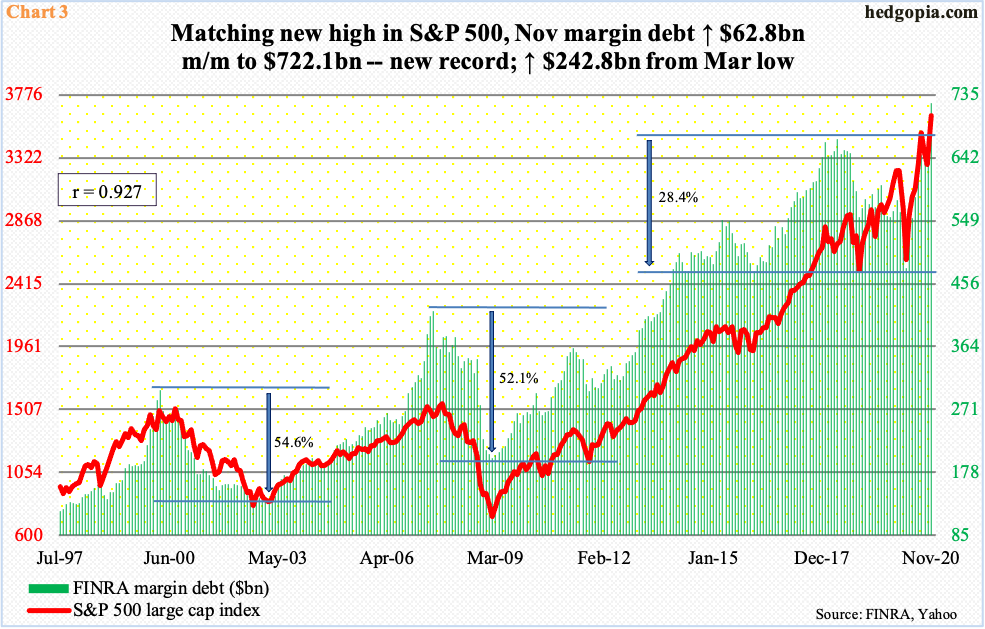

They would also like to see the prevailing momentum in margin debt continue, if not accelerate. In November, FINRA margin debt jumped 9.5 percent, or $62.8 billion, month-over-month to $722.1 billion, eclipsing the prior record of $668.9 billion from May 2018 (Chart 3). To reiterate, the S&P 500 surged 10.8 percent in that month and another 3.7 percent in December. Last month’s data is not out yet, but it is possible margin debt rose to a new high as well.

Since last March, when stocks bottomed, there has been a material rise in investor willingness to take on leverage. Margin debt, too, bottomed in that month, at $479.3 billion, meaning it has gone up 50.7 percent over an eight-month period.

This is where it gets interesting. Going back to September 1997, there have been three other months when margin debt grew north of 50 percent over eight months (chart here) – June 2007 (up 52.6 percent), February 2000 (up 51.4 percent) and March 2000 (up 58.3 percent). Both 2000 and 2007 marked the onset of a bear market – in March and October, in that order. We just had another jump of over 50 percent. Bulls obviously put low odds on the possibility of a repeat of 2000 and 2007.

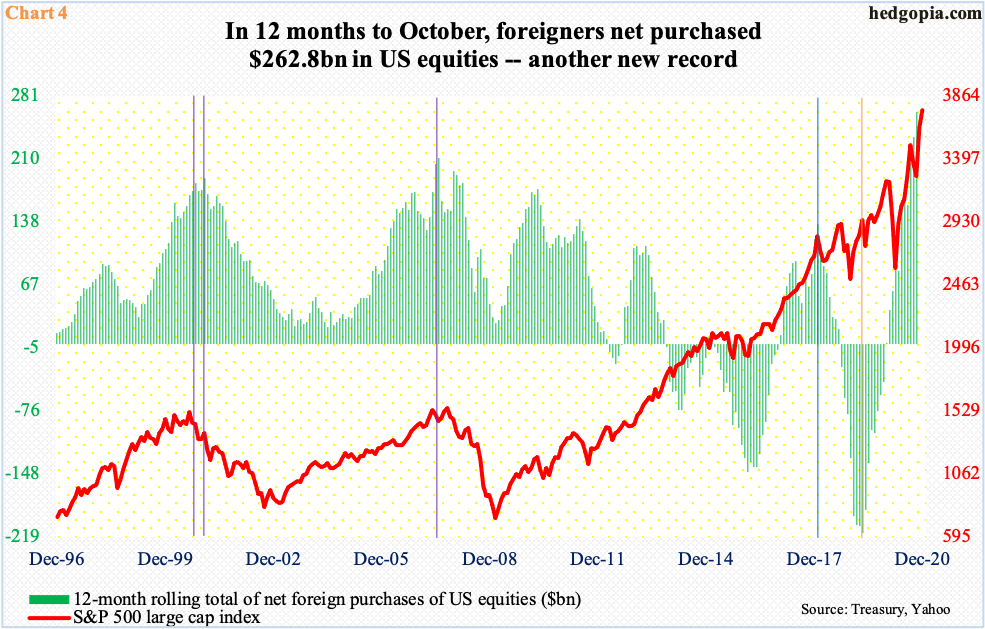

They would also not want foreigners to pull back their horns. Foreigners of late have been aggressively purchasing US equities. In the 12 months to last October, their net purchases equaled $262.8 billion – a record. November’s data will be out in less than two weeks, and given how US stocks fared in that month, in all probability they bought more.

Historically, foreigners’ purchases – or a lack thereof – and the S&P 500 tend to move hand in hand.

In January 2018, their 12-month purchases peaked at $135.6 billion (blue vertical line in Chart 4). The S&P 500 suffered down months in February and March that year, before stabilizing. But foreigners kept reducing exposure. By April 2019, they had net-sold $214.6 billion in 12 months – a record (orange vertical line); by December that year, they had turned into net purchasers, and kept buying even when others were massively liquidating in February and March last year. They were right to do so.

Bulls hope this aggression on the part of foreigners continues.

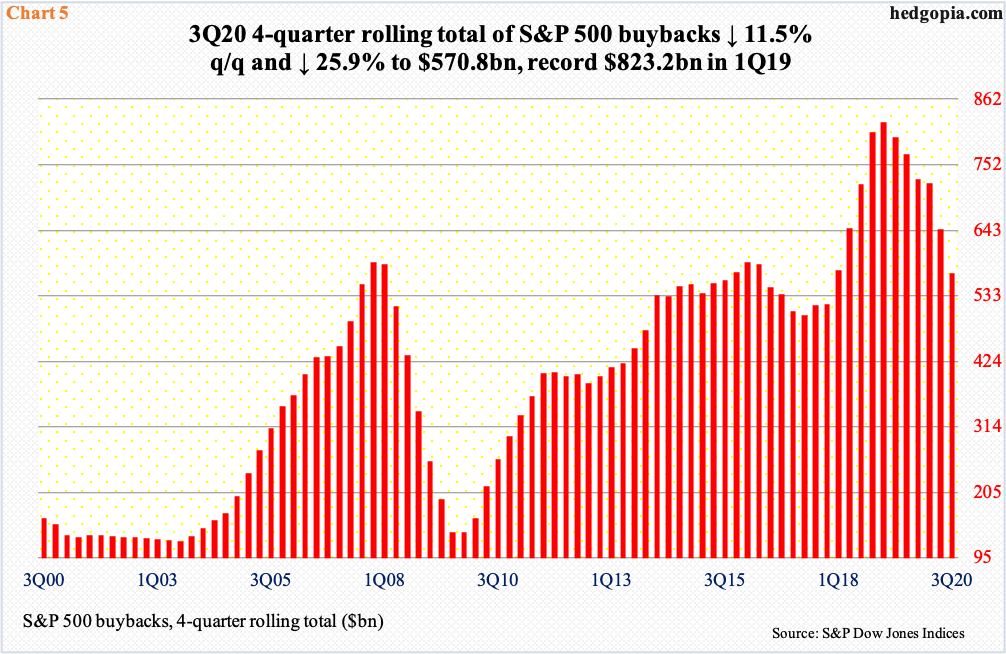

In fact, foreigners, along with margin debt, helped fill a large vacuum left by corporate buybacks.

In 4Q18, S&P 500 companies spent $223 billion in buybacks – a record. Along with $119.8 billion in dividends, the $293.8 billion in operating earnings in that quarter was easily outspent. The blistering pace was simply unsustainable. In 2Q20, buybacks were down to $88.7 billion – an eight-year low – with $101.8 billion in 3Q20. The four-quarter total of $570.8 billion in 3Q20 was an 11-quarter low. This compares with a record $823.2 billion spent in the four quarters through 1Q19 (Chart 5).

The point is, from a massive tailwind at one time, buybacks have turned into a headwind. It is hard to imagine them regaining their old glory anytime soon, but they can at least stabilize. As a matter of fact, if S&P 500 earnings come anywhere close to what they are expected to earn this year, the pace of buybacks likely picks up steam.

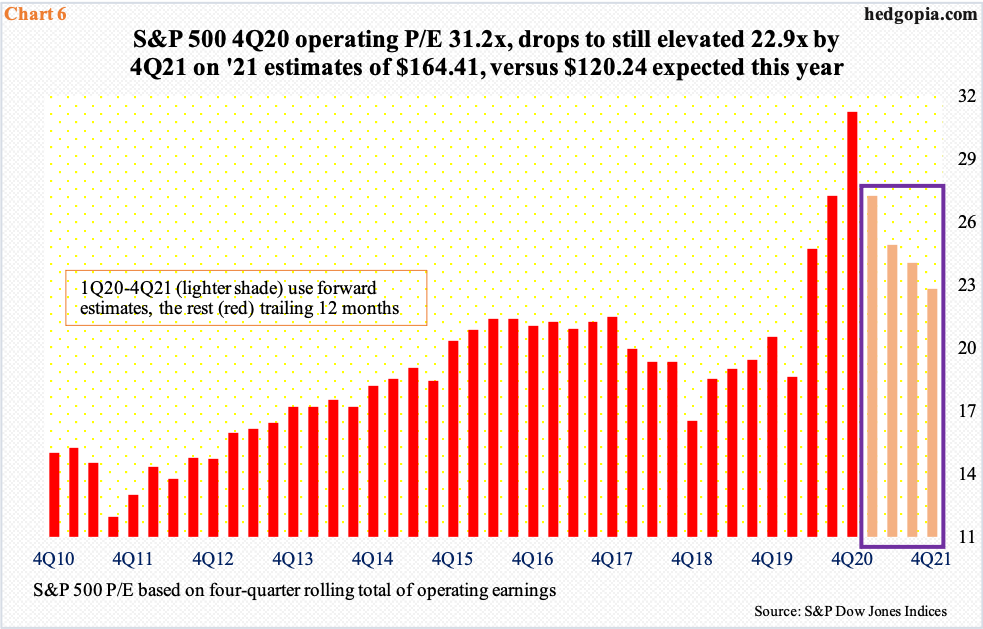

The sell-side has high expectations this year. Operating earnings for S&P 500 companies are expected to surge 36.7 percent from the consensus $120.25 in 2020.

Last March, this year’s estimates were as high as $183.37 before these analysts brought out their scissors. Estimates bottomed at $160.89 mid-July. The upward revision trend that followed peaked mid-December at $166.63, before ending the year at $164.40.

Equity bulls hope the latest downward revision does not turn into a trend. Although the fact remains that historically the sell-side tends to start out optimistic and then gradually lower the numbers as the year progresses. The other thing is that valuations already are at nosebleed territory.

Companies will start reporting their December quarter next week. Using the $36.05 expected to be earned in 4Q20, the S&P 500 traded at a towering 31.2x on trailing four-quarter earnings (Chart 6). Even if this year’s estimates come through, the forward P/E multiple drops to still-elevated 22.9X by 4Q.

The thing is, chasing winners, not worrying much about valuations, has worked thus far. These are obviously folks investing in ‘it is different this time’. A lot of things have to fall into place for them to pull through another solid year, including how flows behave, how margin debt behaves, how foreigners behave or how buybacks behave, for that matter.

A lot of this likely will be called into question should the S&P 500 lose two levels: 3640s, which is where the index peaked on the day the Pfizer news came out, and 3580s, which was the high hit on September 2. Until then, bulls hold the momentum card.

Thanks for reading!