Job openings are at record highs. If past is prelude, this leads to job creation. This time around, thanks to stimulus money, Americans do not seem desperate for jobs – unless wages rise enough to tempt them back into the labor force.

Job openings are going gangbusters.

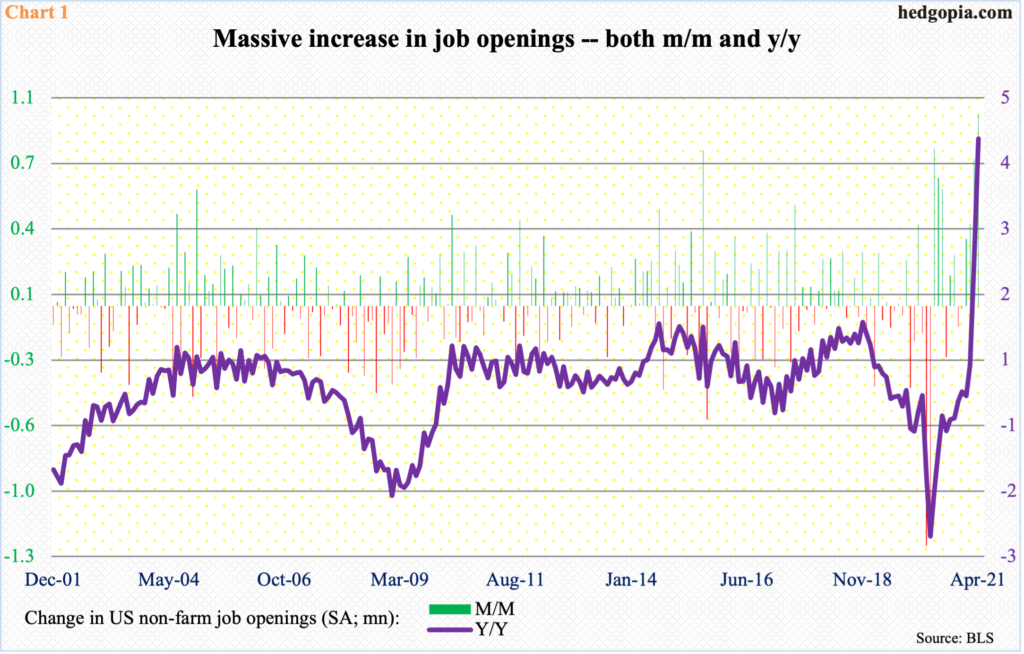

In April, non-farm openings shot up 998,000 month-over-month and 4.66 million year-over-year to 9.29 million – a new record. Both m/m and y/y growth has never been higher (Chart 1).

Post-pandemic, openings hit a low of 4.63 million in April last year. From that low, they have more than doubled. (The momentum in non-farm openings is corroborated by the NFIB job openings sub-index which in May rose four points m/m to 48 – also a fresh record.)

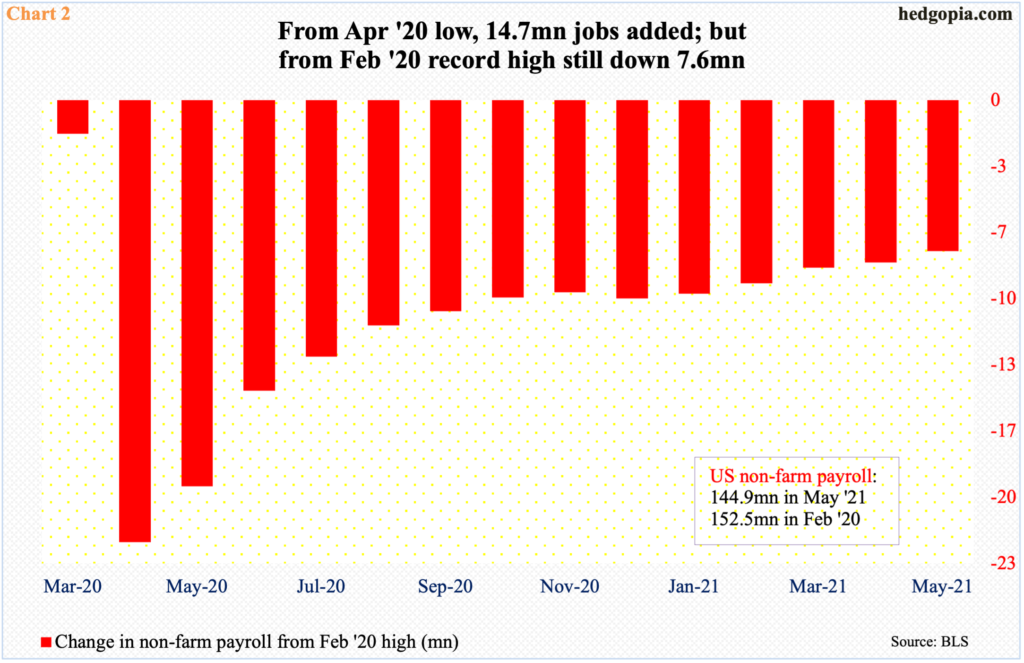

Historically, openings tend to lead employment. From the low of last year’s post-pandemic low, non-farm payroll has shown massive improvement but is yet to post a new high.

In February last year, there were 152.5 million jobs; by April, as the economy shut down, the count abruptly crashed to 130.2 million. From that low through May this year, 14.7 million jobs have been added, but this is still 7.6 million short of the record high from February last year (Chart 2).

If openings are sending the right signal, the gap likely gets filled in due course.

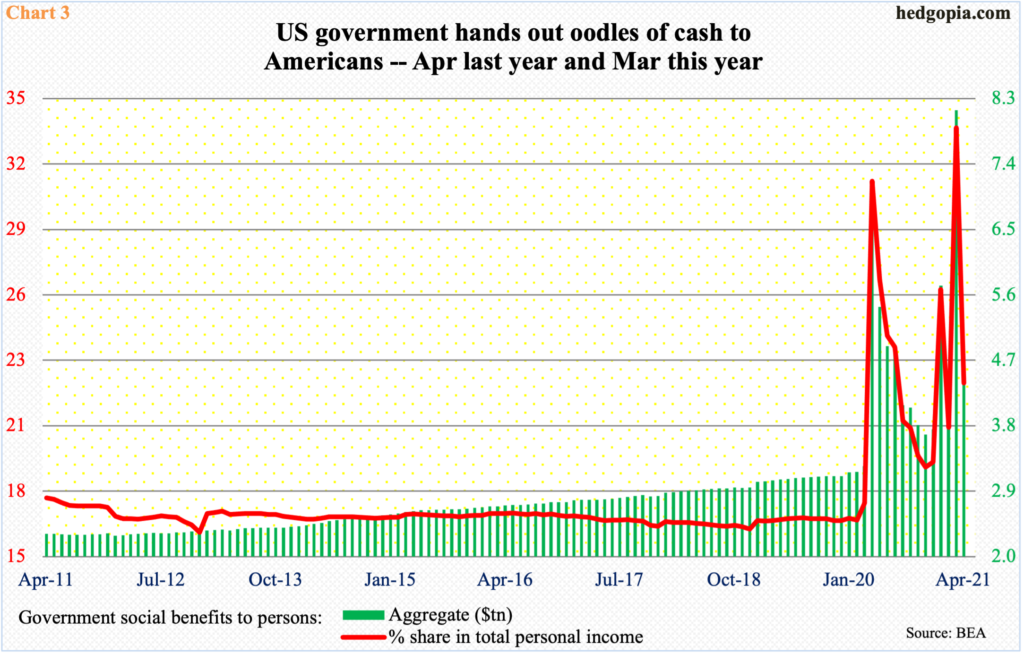

The surge in openings is coming at a time when huge amounts of money have been transferred from the government coffers to the public.

In April last year, as stimulus checks went out, the ‘government social benefits to persons’ line item in the personal income report jumped $3.3 trillion m/m, making up for 31.1 percent of personal income. Then, in March this year, another $4 trillion was handed out, making up for 33.3 percent of personal income (Chart 3).

This put billions in extra money in American’s hands and could be playing a role in why job openings are having a hard time getting snapped up.

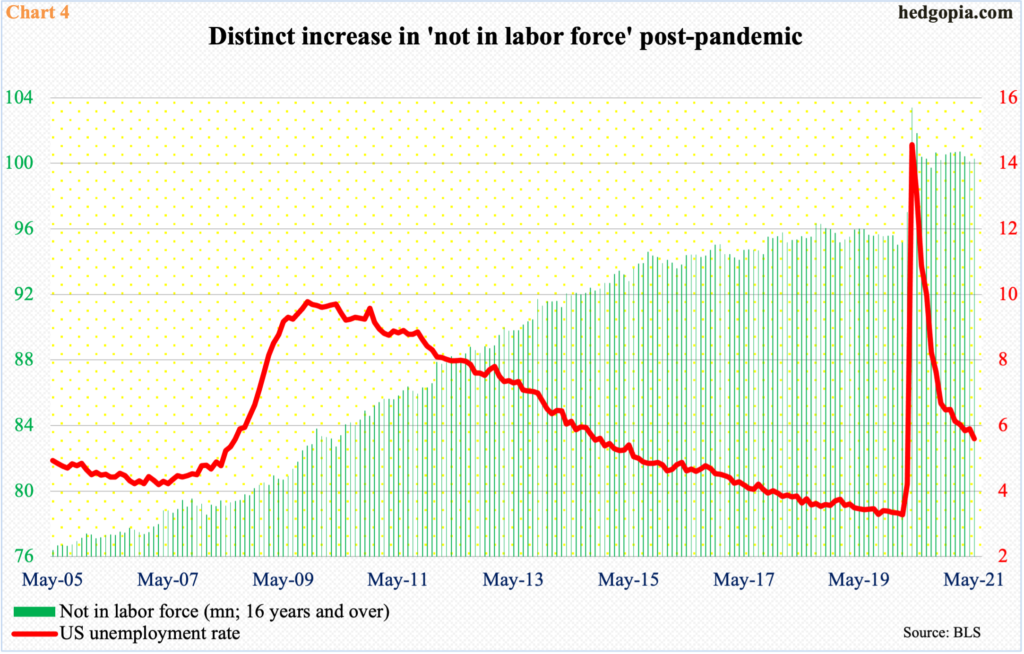

It is not like the labor pool is drained.

Last month, 100.3 million were categorized as ‘not in labor force’. In April last year, post-pandemic, this metric jumped to 103.4 million, and has since stubbornly gone sideways at an elevated level (Chart 4).

In the meantime, the unemployment rate in May was 5.8 percent, which represents substantial improvement from 14.8 percent recorded in April last year but is nowhere near the low of 3.5 percent from February last year.

These metrics will look a lot different if the vacancies out there get filled. In the past, job creation followed openings. This time around, the stimulus money may have thrown a spanner in the works. Job seekers are not desperate. They have cash to fall back on. This raises the possibility that they will not reenter the labor force for the current wages.

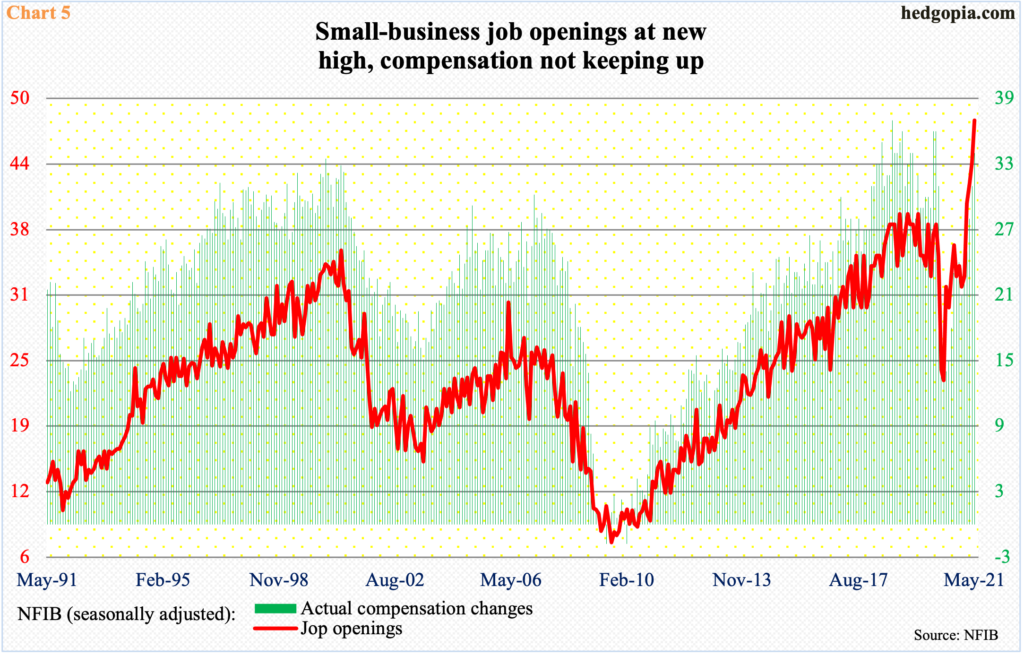

As mentioned earlier, small-business job openings hit a new record in May. In the same month, the ‘actual compensation changes’ sub-index was below the pre-pandemic high from February last year, not to mention the all-time high from September 2018 (Chart 5).

Compensation is not keeping up with the surge in openings. This opens up the possibility of companies needing to raise wages in the outer months in order to meet demand.

Thanks for reading!