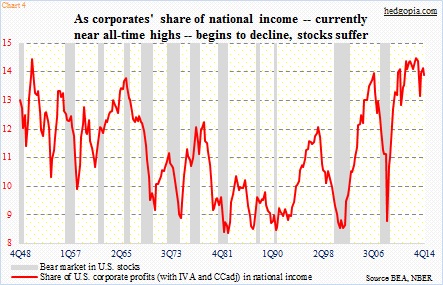

- Share of U.S. corporate profits in national income barely off all-time highs

- Share of software plus R&D in U.S. private fixed investment falling since 2009

- As good a hint as any for corporates to send current margins unsustainable long term?

The role of productivity cannot be stressed enough. It is crucial in raising the living standards of population.

Two components drive gross domestic product: population growth and labor productivity. In the U.S., going back to 1930, population growth has averaged 1.1 percent. For over a decade now, the growth rate has shifted down to sub-one percent, with an average of 0.9 percent between 2002 and 2014. Hence the even more important role of productivity.

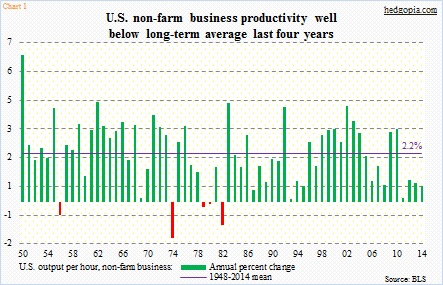

The trend in recent years has not been encouraging, with the average increase in non-farm output per hour the past four years of a mere 0.68 percent, versus the 66-year average of 2.2 percent (Chart 1).

Naturally a question arises as to if this is just a pause or a permanent downward shift in long-term trend.

It is a question every economist out there is probably trying to get his/her arms around, but there is no easy answer.

Nonetheless, there are places where we can look for hints.

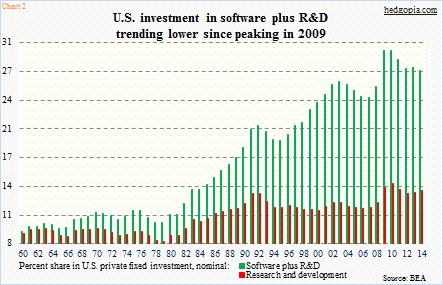

Chart 2 plots the share of software ($305 billion in 2014) plus research and development ($301 billion) in U.S. non-residential fixed investment ($2.2 trillion). The green bars combine software and R&D, and the red ones just R&D. (Software does not include embedded software in computers and other equipment, and R&D excludes expenditures for software development, which is included in ‘software’.)

Software investments started growing in the early ‘80s, overtaking R&D by 1999 ($157 billion versus $156 billion, respectively, in that year). Makes total sense given the increasing role of software in today’s world (think of GOOG, FB, TWTR, etc.). Combined, software and R&D are at a new high.

All good.

But here is a killjoy. As a share of non-residential fixed investment, the green bars peaked in 2009 and the red ones in 2010 (Chart 2). Once again, going back to Chart 1, not sure if there is correlation here, productivity fell off the cliff in 2011, followed by sub-par performance in 2012-2014.

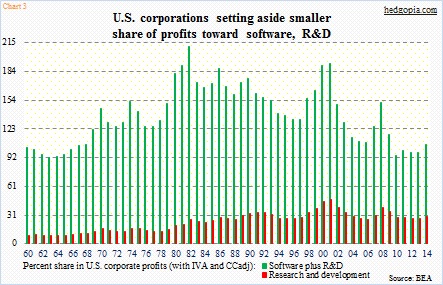

This was not taking place because corporations lacked the wherewithal. Corporate profits (with inventory valuation and capital consumption adjustments) in 2014 were $2.09 trillion, less than a percent off the record $2.11 trillion the year before. As a matter of fact, corporations since 2001 have been setting aside fewer profit dollars for software and R&D (Chart 3). The trend is decidedly down, although for the first time in five years it exceeded 100 percent last year.

But why are they penny-pinching when it comes to investments?

One routine rationalization is that corporations have been spending way too much on buybacks and dividends – $553 billion in buybacks and $350 billion in dividends spent by S&P 500 companies in 2014 (courtesy of S&P).

Here is a couple of other alternatives.

One, there is an ongoing shift from hardware to software. Given trends in cloud computing, software-defined networking, etc., software is increasingly taking over from hardware. It is much cheaper to run this blog off of a server somewhere in the cloud than if I were to have a server myself. This also applies to, let us say, running an HR app on WDAY cloud versus installing software on the premises. But if this is what is solely leading to lower software investments, the red bars in both Charts 1 and 2 should be trending higher, but they are not.

Two, corporations do not believe the present trend of profitability is sustainable. Operating margins for S&P 500 companies were nine percent in 4Q, down from 3Q’s 10.1 percent but very high historically. The share of U.S. corporate profits in national income is barely off its all-time highs (Chart 4). All the more reason for corporations to think this is not sustainable long-term. At least going back to the late ‘40s, the series has tended to mean-revert. Once it starts to drop, especially from as high a perch as it is now, it has brought bad news for stocks.

Whatever the reason, or a set of reasons, investments have not kept up with corporate profits. And that cannot be good news for productivity in outer years.