Debt can be both a boon and a bane.

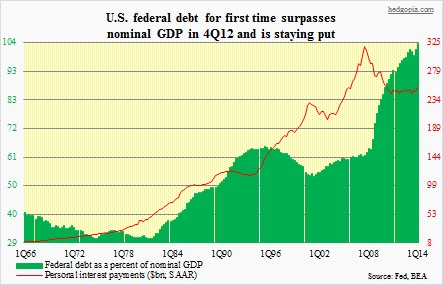

Used properly, it can be a very useful tool – be it to an individual, a business, or a government. Too much of it at the same time can unleash destructive forces. Within a company, for instance, a right mix between debt and equity can greatly enhance return on equity. On the other hand, history is littered with companies that overleveraged themselves into bankruptcy/oblivion. The trick is to figure out the right mix, and stay disciplined. The key word is discipline, and it is too easy to lose sight of it. Individuals, businesses as well as sovereigns are all prone to falling into this trap. Post-Great Recession, Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff, in their book This Time is Different, argued that debt-to-GDP ratios over 90 percent are associated with lower growth. In the accompanying chart, U.S. federal debt ($17.6tn by 1Q14) is calculated as a percent of nominal GDP ($17tn). It has now crossed 100 percent. Since the end of the Recession, real GDP growth has averaged less than two percent annually, well below what has been historically. In the first half this year, growth may very well be flat. The attempt here is not to vindicate Reinhart’s and Rogoff’s claim, or refute it for that matter, rather to show the pros and cons of debt.

Used properly, it can be a very useful tool – be it to an individual, a business, or a government. Too much of it at the same time can unleash destructive forces. Within a company, for instance, a right mix between debt and equity can greatly enhance return on equity. On the other hand, history is littered with companies that overleveraged themselves into bankruptcy/oblivion. The trick is to figure out the right mix, and stay disciplined. The key word is discipline, and it is too easy to lose sight of it. Individuals, businesses as well as sovereigns are all prone to falling into this trap. Post-Great Recession, Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff, in their book This Time is Different, argued that debt-to-GDP ratios over 90 percent are associated with lower growth. In the accompanying chart, U.S. federal debt ($17.6tn by 1Q14) is calculated as a percent of nominal GDP ($17tn). It has now crossed 100 percent. Since the end of the Recession, real GDP growth has averaged less than two percent annually, well below what has been historically. In the first half this year, growth may very well be flat. The attempt here is not to vindicate Reinhart’s and Rogoff’s claim, or refute it for that matter, rather to show the pros and cons of debt.

The debate is very topical these days as most of the developed nations are neck-deep already, and it is that part of the world that is also struggling to grow. IMF figures show that in 2013 the amount of public debt in Japan was 243 percent of GDP! Over in Europe, according to Eurostat, Germany stood at 78 percent, France 94 percent, the U.K. 90 percent and Italy 133 percent. In truth, there may or may not be a magic threshold of a debt-to-GDP ratio which, once hit, causes deceleration in growth. The ratio may even vary from one country to another, or even on who owns how much of debt. For instance, one-third of U.S. public debt is owned by foreign countries, versus less than five percent in Japan. More important discussion in this regard is perhaps if these over-indebted countries are working toward reducing their debt load. The short answer is no. Even China is worse off versus six or seven years ago. Stung by exports slowdown during the global financial crisis, that nation introduced aggressive fiscal stimulus packages, resulting in a swelling of local government debt. Abenomics in Japan is essentially seeking to treat the ills of excessive debt by taking on more debt – unsuccessfully, of course. The U.S. is not an exception in this regard. In six years, the Fed has increased its balance sheet by $3.5tn, to $4tn, buying up U.S. treasuries and mortgage-backed securities. In seven years, the debt load of the federal government has doubled.

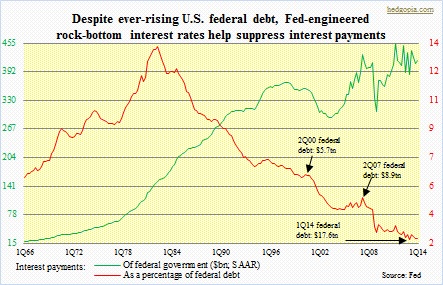

One of the reasons why an increasing debt load increasingly becomes a burden is through interest payments. Seven years ago, when U.S. federal debt was about half what it is today, interest payments were similar, give and take. Rates were much higher back then. Today, they are much lower – artificially lower. The prevailing interest rates are no longer determined in the markets, rather by the Fed, which feels obligated to keep them suppressed in order to spur growth. It is another discussion altogether as to if at this stage of the economic cycle what the Fed is doing is helping or hurting the economy. What we do know is that interest payments as a percent of federal debt are at all-time lows. If they are allowed to normalize and rates head higher, interest payments will begin to bite. This is true in the case of individuals, corporations as well as governments. As the first chart shows, personal interest payments, which peaked at $318bn SAAR in 3Q07, are $65bn lower now. Yes, household liabilities have come down from $14.6tn in 3Q08 to $13.8tn in 1Q14, but (1) they have also doubled since 1Q00, and (2) most of the decline in interest payments is due to lower interest rates. Leverage has also gone up among corporations, thanks to share buybacks and increased dividend payments.

One of the reasons why an increasing debt load increasingly becomes a burden is through interest payments. Seven years ago, when U.S. federal debt was about half what it is today, interest payments were similar, give and take. Rates were much higher back then. Today, they are much lower – artificially lower. The prevailing interest rates are no longer determined in the markets, rather by the Fed, which feels obligated to keep them suppressed in order to spur growth. It is another discussion altogether as to if at this stage of the economic cycle what the Fed is doing is helping or hurting the economy. What we do know is that interest payments as a percent of federal debt are at all-time lows. If they are allowed to normalize and rates head higher, interest payments will begin to bite. This is true in the case of individuals, corporations as well as governments. As the first chart shows, personal interest payments, which peaked at $318bn SAAR in 3Q07, are $65bn lower now. Yes, household liabilities have come down from $14.6tn in 3Q08 to $13.8tn in 1Q14, but (1) they have also doubled since 1Q00, and (2) most of the decline in interest payments is due to lower interest rates. Leverage has also gone up among corporations, thanks to share buybacks and increased dividend payments.

So what are the long-term repercussions? First, the Fed will need to keep rates suppressed for a very long time, as leverage has pervaded the entire economy. Second, GDP growth is bound to remain subdued. Assuming a scenario in which growth begins to stabilize, thereby also causing stability in interest rates – which probably means higher rates, hence higher interest payments – that in and of itself will act as a built-in brake. In 1Q14, interest payments as a percent of federal debt were 2.37 percent. Simplistically, let us assume this rises by a mere 50 basis points (was 2.86 percent in 1Q11), at the current debt level we are talking $503bn in interest payments, $86bn more than what was paid out in 1Q14. That additional money has to come from somewhere – either government spending gets cut, or spending remains the same and taxes are raised, or the status quo continues – meaning deficit spending continues and debt continues to pile on.