The 10-year treasury yield more than doubled in five months, completing a measured-move target of an inverse-head-and-shoulders breakout in early January. This is coming at a time when the Fed has signaled it will use both conventional and unconventional tools to tighten to aggressively fight inflation. This in all probability will impact growth. These securities could begin to attract buying interest.

The 10-year treasury yield has been running hard the past five months and could be in the process of taking a breather, or reverse outright. In early December last year, rates hit 1.34 percent; on April 21, they tagged 2.95 percent, which was the highest print since December 2018.

On the daily, the 10-year in the right circumstances for bond bears can still add to gains should 2.93 percent gets decisively taken out. Even in this scenario, odds of a peak have grown.

In early January, rates broke out of an inverse-head-and-shoulders pattern. A measured-move target of this breakout comes to high-1.9s, which has been nearly hit (Chart 1). On the weekly, some stalling action is evident in the last three weeks.

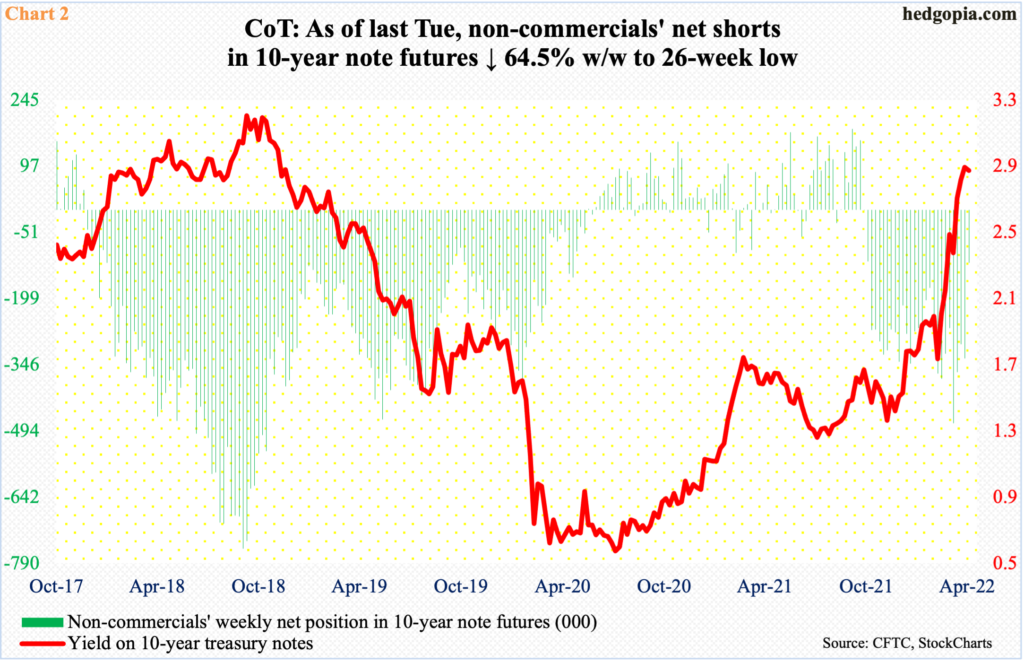

At least in the futures market, non-commercials are acting as if 10-year notes have reached an attractive buying point.

As recently as the week to March 29, these traders were sitting on 476,557 net shorts in 10-year note futures – the highest since November 2018. In the week to last Tuesday, they cut them down to a 26-week low of 117,817 contracts (Chart 2).

They are still net short but could very well be on a path to going net long.

There is no shortage of arguments to go short long bonds. Inflation is running amok. Consumer inflation is at multi-decade highs.

In the 12 months to March, headline and core PCE (personal consumption expenditures) – the Federal Reserve’s favorite measure of consumer inflation – jumped 6.6 percent and 5.2 percent respectively, with the former the steepest since January 1982; February’s 5.3 percent was the fastest rate of core PCE since April 1983. This came out last Friday.

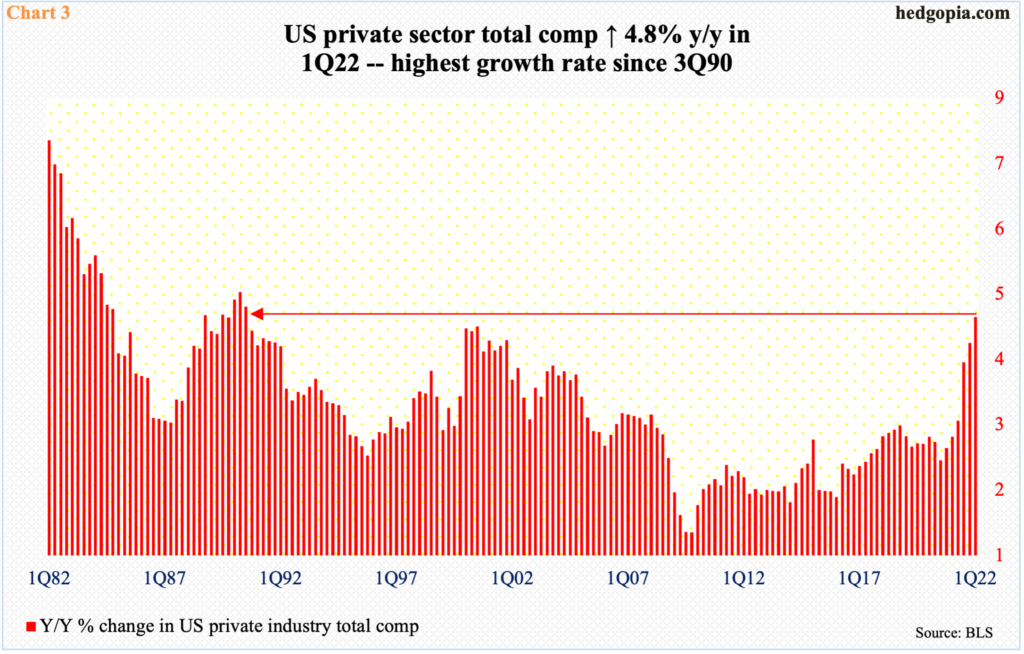

Also on Friday, the employment cost index for the first quarter was published and it was clear the rise in inflation is being institutionalized.

In 3Q20, private-sector total compensation was growing at a rate of 2.4 percent year-over-year, before trending higher on a sustained basis. In the last quarter, the metric grew 4.8 percent. This was the highest growth rate since 3Q90 (Chart 3).

Having to deal with a jump in both consumer prices and wages – not to mention home prices – the Fed increasingly is in a no-win situation. Until not too long ago, it was adamant inflation was transitory. Not anymore.

In late March, Jerome Powell, Fed chair, said that the central bank, if necessary, would be open to raising rates by a half-point at multiple FOMC meetings, adding that it could get “restrictive” to slow economic growth and possibly raise the unemployment rate to tame high inflation. Since that meeting, Powell, and other members, have sounded even more hawkish.

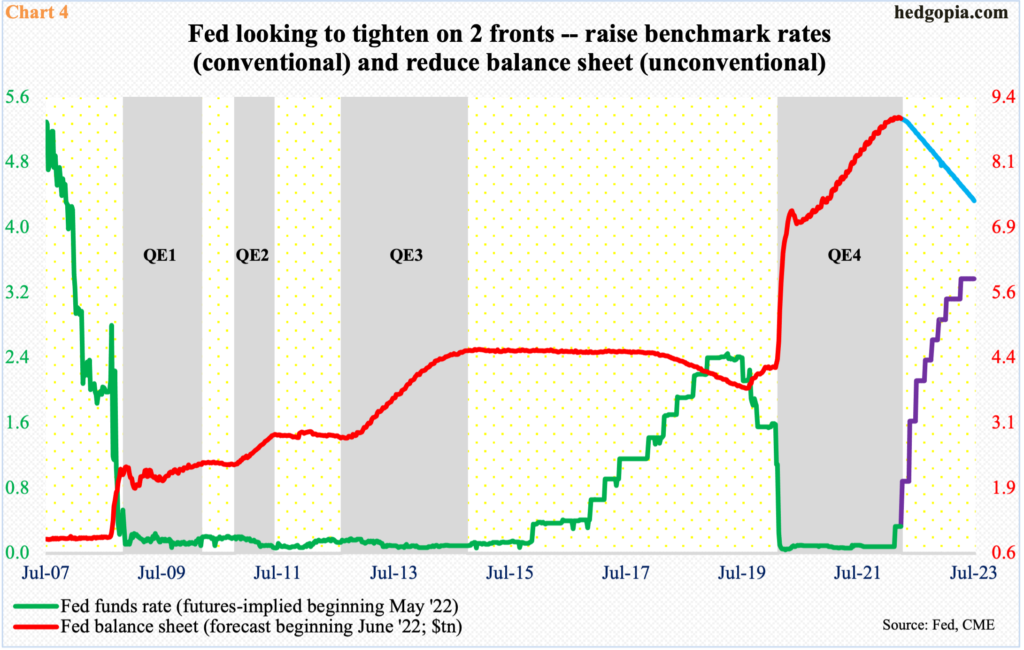

Concurrently, it also wants to reduce its balance sheet, which went from $4.24 trillion in early March 2020 to $8.97 trillion two weeks ago; last week (as of Wednesday), it ended at $8.94 trillion. Minutes of the March 15-16 meeting showed officials generally agreed to cut up to $95 billion a month from the bank’s asset holdings. At this pace, the balance sheet could reach $7.4 trillion by July next year (Chart 4).

At the same time, the Fed is pushing up its benchmark rates. For the first time since December 2018, the fed funds rate was raised by 25 basis points in the March meeting to a range of 25 basis points to 50 basis points. In the meeting this week, a 50-basis-point move is priced in. In the futures market, traders are betting rates will reach 325 basis points to 350 basis points by July next year.

The Fed is using both conventional (rates) and unconventional (balance sheet) tools to tighten. If the aggression persists, repercussions will be felt.

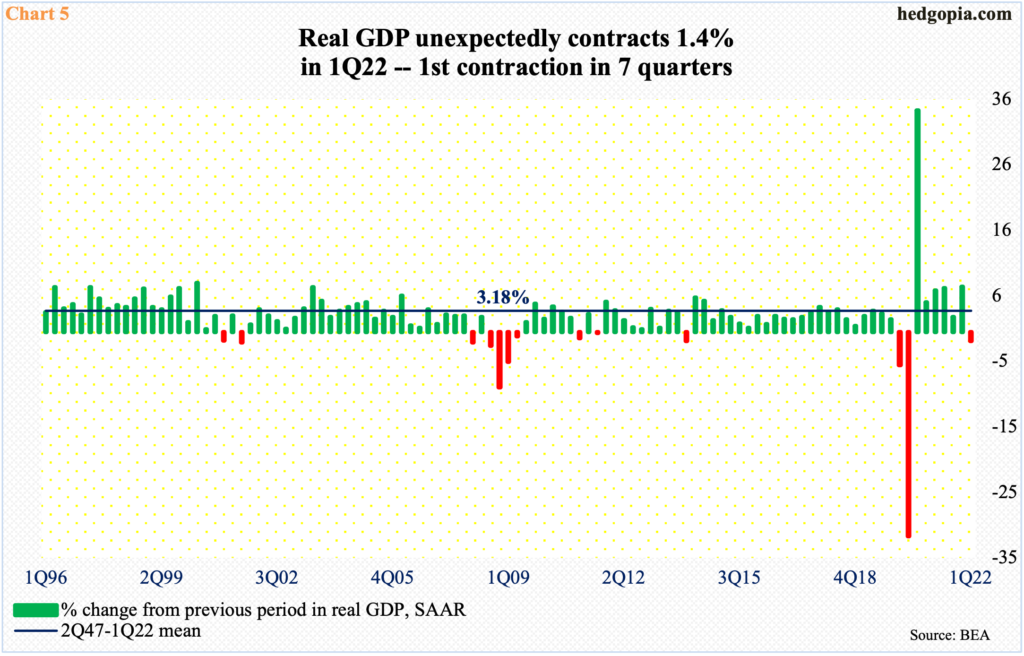

Growth will decelerate in the best case and even contract in the worst. Not to overemphasize but real GDP in the last quarter unexpectedly dropped 1.4 percent (Chart 5). The first contraction in seven quarters was primarily due to a deceleration in private inventory investment and rising imports; consumer spending held up well.

But the fact remains that the red hot, post-pandemic pace was bound to soften. The question is of magnitude of this softening. A tighter interest rate environment – although from ultra-loose conditions – will not help.

These new dynamics can begin to attract interest in these securities, which have taken a big hit as rates surged. Currently, the 10-year has priced in elevated inflation and the Fed’s imminent response to it, but not growth deceleration/contraction. Rates will begin a new trend – this time downward – as more and more fixed-income investors buy into this thesis.

Thanks for reading!