One valuation tool equity bulls consistently use to justify current stock valuations – as well as to argue for further multiple expansion – is by comparing bond yield to earnings yield. There is a metric known as ‘bond equity earnings yield ratio’, which measures the relationship between these two yields. The numerator, for instance, could be the 10-year Treasury yield, and the denominator the earnings yield of the S&P 500. Earnings yield is simply the inverse of P/E.

So theoretically, a ratio of one would simply indicate that investors perceive an equal amount of risk in bonds and stocks. But it is not that black and white.

The 10-year closed Thursday yielding 2.5 percent. Reported earnings the last 12 months for S&P 500 companies were just under $111, so based on this the current P/E is 16.9 percent, resulting in an earnings yield of 5.9 percent. Perma-bulls nevertheless like to use either the expected earnings for FY14 ($114, hence an earnings yield of 6.1 percent) or for the next 12 months ($124 for an earnings yield of 6.6 percent!). So depending on which earnings we use as a base, the ‘bond equity earnings yield ratio’ is 0.42 or 0.41 or 0.38. If we use the 30-year bond (yield of 3.3 percent), then the ratio rises to 0.56, 0.54, or 0.50.

The 10-year closed Thursday yielding 2.5 percent. Reported earnings the last 12 months for S&P 500 companies were just under $111, so based on this the current P/E is 16.9 percent, resulting in an earnings yield of 5.9 percent. Perma-bulls nevertheless like to use either the expected earnings for FY14 ($114, hence an earnings yield of 6.1 percent) or for the next 12 months ($124 for an earnings yield of 6.6 percent!). So depending on which earnings we use as a base, the ‘bond equity earnings yield ratio’ is 0.42 or 0.41 or 0.38. If we use the 30-year bond (yield of 3.3 percent), then the ratio rises to 0.56, 0.54, or 0.50.

Based on this, stocks are a great bargain. But is it? Or is the metric a proper tool at all in the current environment?

First and foremost, back in the bubbly late-1990s, stocks sold for a P/E of 60, for an earnings yield of 1.7 percent; the 10-year was yielding in the six percent range, and the 30-year a tad above that. Using this as an investing tool, that was a great time to unload stocks and load up on bonds. So there is nothing wrong with the tool per se. It is just that in the present circumstances this is a lousy metric to rely on.

Here is why.

As part of QE, the Fed has been buying a substantial portion of Treasury issuance. A lack thereof in all probability would put upward pressure on the belly and long-end of the yield curve. If we follow this logic, then it follows that a higher yield would be problematic for the economy, which continues to be very tentative, and this in turn would create a problem for corporate earnings. Under this scenario, the $100 reported for 2013, and $111 for the last 12 months, would probably not be achieved. It is all artificially propped up.

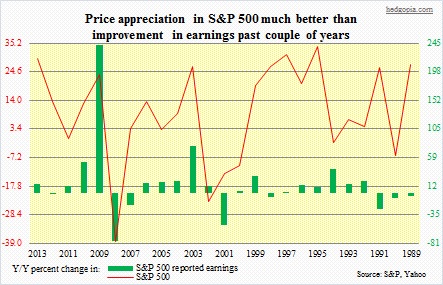

Secondly, over the long term, corporate earnings closely track nominal GDP. Post-WWII, growth in both have averaged a little over seven percent. But here is the thing. In 2013, 2012 and 2011, nominal GDP grew 3.4 percent, 4.6 percent and 3.8 percent, respectively. Reported earnings for S&P 500 companies in the meantime grew 15.8 percent, flat, and 12.4 percent, in that order. Fed-engineered low interest rates have helped both corporate balance sheet (debt refinancing) and income statement (lower interest payments). Cash flow is healthy, and share buybacks have helped the bottom line. Plus, of course, corporations have been cautious on the investment front – both capital and labor. Margins are already at all-time highs. S&P estimates S&P 500 1Q14 operating margins at 9.79 percent, a potential record. Sustainable? Nope.

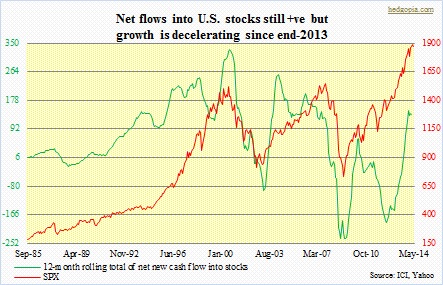

Thirdly, a bond gets bid up – hence lower yield – as it attracts new capital. Availability of capital is not infinite. Any penny that goes into bonds could have alternatively gone into stocks. So unless we assume that money leaves bonds – not a base case scenario here – and into stocks, the gulf between bond yield and earnings yield will probably stay that way. As the accompanying chart shows, stocks have been attracting money since early last year, with some deceleration in recent months. For multiple expansion to occur, stocks need to attract new capital, and that cannot occur as capital is also flowing into bonds.

Thirdly, a bond gets bid up – hence lower yield – as it attracts new capital. Availability of capital is not infinite. Any penny that goes into bonds could have alternatively gone into stocks. So unless we assume that money leaves bonds – not a base case scenario here – and into stocks, the gulf between bond yield and earnings yield will probably stay that way. As the accompanying chart shows, stocks have been attracting money since early last year, with some deceleration in recent months. For multiple expansion to occur, stocks need to attract new capital, and that cannot occur as capital is also flowing into bonds.

Finally, when demand for bonds rises, investors obviously do not have high hopes for the economy – or at least do not expect acceleration anytime soon. By default, this would suggest corporate earnings that could come under pressure, which sooner or later would get reflected into stocks. But this is precisely when the ‘bond equity earnings yield ratio’ is tempting us – wrongly at that – to get into stocks.