Next Wednesday, the Fed will have eased. Besides being a first cut in nearly 11 years, the move has the potential to also impact the bank’s balance sheet and commercial bank earnings.

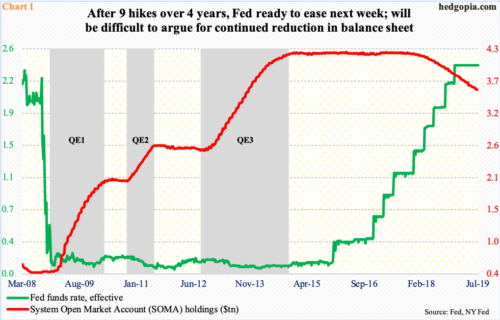

The Fed is all set to reduce its policy rate next week. After nine hikes over four years through last December, the Fed funds rate currently stands at 225 to 250 basis points. A 25-basis-point cut next Wednesday is baked in. Fed funds futures have priced in another cut in September, and possibly – not probably – another in December.

Besides marking as a reversal in the Fed’s tightening bias, this has the potential to also have an impact on at least two other fronts.

Post-financial crisis, the central bank’s balance sheet grew, as it began to purchase Treasury and mortgage-backed securities. System Open Market Account (SOMA) holdings went from $500 billion in December 2008 to a peak of $4.24 trillion in April 2017 (Chart 1). The bank began to run them down in October that year. It continues to reduce its balance sheet, but since May this year the pace of reduction has tapered off. As of Wednesday last week, SOMA holdings were $3.60 trillion, down $641 billion from the April 2017 peak. In March this year, the Fed announced that the balance-sheet normalization program would end in September.

Therein lies the rub.

If the Fed acquiesces to current market demands, by year-end the fed funds rate will at least range between 175 and 200 basis points. When it is easing on the conventional front, it likely becomes awfully difficult to continue to tighten using an unconventional tool like balance sheet. This can have implications for all kinds of assets, not the least of which are equities and the long end of the Treasury yield curve.

Then, there is the issue of interest on excess reserves (IOER).

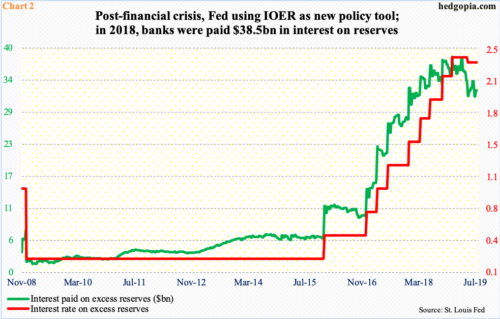

Commercial banks are required to hold a certain portion of their deposits as cash in a Fed account. These are known as required reserves. Should they choose, these banks can hold more than they are required. These are called excess reserves. As, post-financial crisis, the fed expanded its balance sheet, excess reserves grew, from a negligible amount pre-crisis to $2.72 trillion in September 2014. Last week, it stood at $1.38 trillion.

Here is the thing.

Ordinarily, excess reserves do not earn a profit. Banks would rather lend these funds and earn an interest. Post-crisis, however, the Fed started paying interest on them, and, by doing so, effectively came up with a new policy tool to influence banks’ lending behavior. Currently, IOER stands at 2.35 percent. It moves together with the fed funds rate. If IOER is higher than the fed funds rate, banks would be more than happy to deposit their excess reserves at the Fed rather than lend them to other banks at the fed funds rate.

A lower fed funds rate, therefore, will mean lower interest income for these banks. Chart 2 plots both IOER and interest payment thereof to banks. The latter has been in decline since March this year but remains massive. In 2018, the Fed paid banks $38.5 billion in interest on reserves. This is no chump change, and will increasingly be at risk the more the Fed eases.

Thanks for reading!