Foreigners in the aggregate have been dumping Treasury notes and bonds. The Fed has been buying these securities, but less and less so. Given the soaring budget deficit and the need to issue new debt, the status quo cannot continue. Else, the 10-year rate, currently rangebound, will jump. A leveraged economy cannot tolerate higher rates.

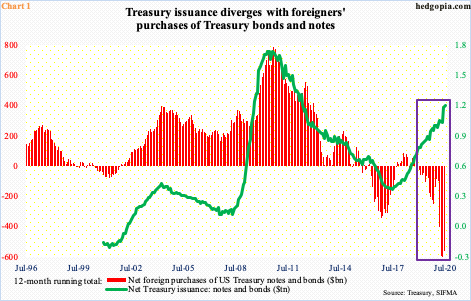

Foreigners purchased $28.9 billion in Treasury notes and bonds in June. This is quite a U-turn from March when they sold $310.8 billion worth. However, the overriding trend for a while now has been that of selling.

In the 12 months to June, foreigners dumped $561.3 billion in these instruments, down slightly from record selling of $600.1 billion in May (Chart 1). On a 12-month basis, their net purchases went negative in January last year and have stayed there since.

Foreigners’ exodus is in clear divergence with the Treasury’s issuance of notes and bonds.

Ordinarily, this is no bond friendly. Less demand for 10-year notes translates to upward pressure on the yield.

On March 9, however, the 10-year yield (0.67 percent) touched an all-time low of 0.40 percent. Before this, rates peaked at 3.25 percent in October 2018, before progressively heading lower. This was about the time foreigners began to dump Treasury securities. If they were the only variable, this should have put upward pressure on the 10-year rate, but apparently that is not the case.

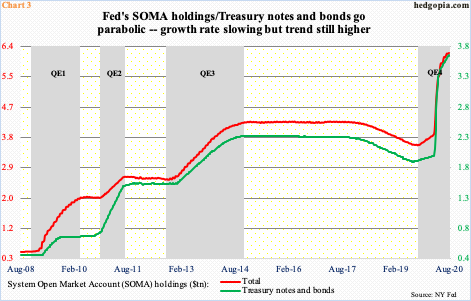

Mid-August last year, the Federal Reserve’s holdings of Treasury notes and bonds bottomed at $1.93 trillion. A few weeks later, in September, SOMA (System Open Market Account) holdings bottomed at $3.55 trillion. They began rising, but it was not until March this year both took off (Chart 3).

From early March to last Wednesday, holdings of notes and bonds went from $2.03 trillion to $3.67 trillion. This pretty much took care of the lack of demand for treasury securities elsewhere.

The 10-year rate the past five months has pretty much gone sideways – between 0.74 percent and 0.57 percent (Chart 2). Last Thursday, the upper end was just about tested with an intraday high of 0.73 percent. Rates have come under pressure since. The 50-day moving average at 0.64 percent is nearby. The 10-day is beginning to rise, and the 20-day is flattish to slightly up. Should these averages hold and rates rise, that would mean the supply-demand dynamics are beginning to favor bond bears (on price).

Foreigners have been net sellers for a while now. The Fed has been buying, although the pace of buying has slowed down, with purchases of $11.3 billion last week versus $335.7 billion in the week to April 1. Should this trend continue, it is only a matter of time before a range breakout occurs on the 10-year rate (Chart 2).

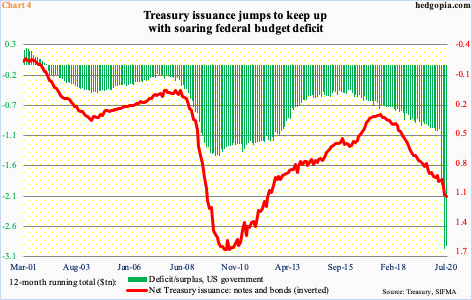

There is a bigger issue at hand, which is that of a widening gap between the government’s receipts and outlays.

In the 12 months to July, the budget deficit amounted to $2.92 trillion, just slightly below $2.98 trillion in the prior month. One year ago, the red ink totaled $961.8 billion. To meet this shortfall, Treasury issuance has gone up as well, with the 12-month total through July of $1.17 trillion.

In the current economic environment, the deficit, if anything, is headed higher, which means Treasury issuance will have to rise as well. This suggests the status quo, in which foreigners have been selling and the Fed has been buying less and less, cannot continue. Else, rates will increase, maybe even meaningfully. A leveraged economy will not be able to take this.

Thanks for reading!