“The assessment will take into account a wide range of information, including measures of labor market conditions, indicators of inflation pressures and inflation expectations, and readings on financial and international developments.”

The above is from the October 28th FOMC statement – essentially telling us what the Fed will be watching before deciding if to raise the fed funds rate at the December meeting.

Despite signs of deceleration in recent months, the U.S. jobs market is hanging in there, having averaged 198,000/month non-farm jobs year-to-September.

Global market jitters in August and September that followed China’s August devaluation of yuan have quieted down, with strong rallies in equities.

It is the inflation – and expectations thereof – that is not falling in line.

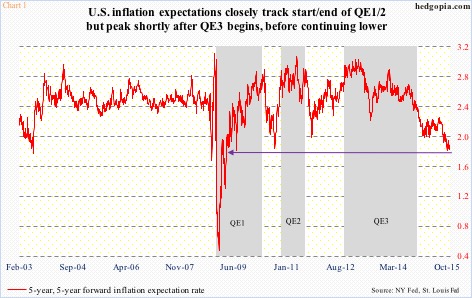

As the FOMC statement makes it clear, the Fed watches inflation expectations, both market- and survey-based.

As far as markets are concerned, inflation is expected to remain subdued as far as the eye can see. The red line in Chart 1 is five-year inflation expectation five years from now. The oodles of QE money that got thrown at the system have been unable to ignite inflation expectations. The red line peaked over two years ago, and made a six-plus-year low of 1.75 percent in late September. It has inched higher in the past month, but nothing to write home about.

Since the FOMC statement last Wednesday, there have been three new releases on inflation/wage pressure – or a lack thereof – and they are all mellow. More ammo for FOMC doves!

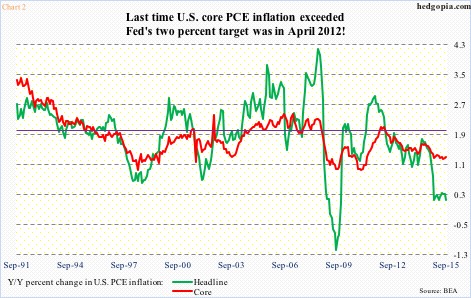

Chart 2 plots the year-over-year increase in the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index – both headline and core. This is the Fed’s favorite measure of consumer inflation.

In September, core PCE grew at a mere 1.31 percent. July’s 1.25 percent was the lowest since March 2011. The last time this measure of inflation grew at the Fed’s desired target of two percent was back in April 2012; even back then, it stayed north of two percent for only four months before coming under renewed pressure.

Incidentally, the consumer price index is running a lot higher, with core CPI rising at 1.9 percent in the 12 months through September – the largest increase since July last year. And it is the CPI that is used for cost-of-living adjustments (COLA) for social security, etc. But the Fed prefers to focus on core PCE… which has a long way to go before it hits the two-percent target.

The GDP price deflator portrays the same trend. In the third quarter, it increased at 0.3 percent quarter-over-quarter, near decade lows (Chart 3). In fact, the red line in the chart came very close to going negative in 4Q14, which was only up 0.2 percent. This would be the first time since 1Q52 (arrow) that the deflator would have dipped into negative territory in non-recessionary times. That was averted in 4Q14, but the fact remains that there is not much upward pressure.

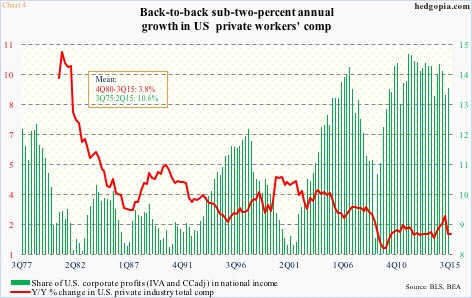

Ditto with wages.

Economists were waiting with abated breath the employment cost index for the third quarter. Earlier in 1Q15, private-sector compensation increased at 2.8 percent annually. This was better than the slightly above two percent pace that average hourly earnings have been growing on a monthly basis. Optimists were hoping the 1Q15 reading was a harbinger of things to come. Apparently not. Total comp (both wages and salaries, and benefits) decelerated to 1.9-percent growth in the second quarter, with the third quarter unchanged – for back-to-back sub-two-percent growth (Chart 4).

Prospects for wage push inflation are non-existent in the U.S. economy. In a business versus labor duel, the former is winning hands down, and this dynamic is unlikely to change anytime soon.

With this as a background, if the Fed puts equal emphasis on its dual mandate – as laid out in the opening sentence – it will be awfully hard for it to move in December.

Thanks for reading!