Job openings are at record highs. Of its dual mandate of maximum employment and price stability, the Fed is singlehandedly focused on the former, being oblivious to rising consumer prices. If these openings get gradually filled, resulting in continued upward pressure on wages, the central bank will have to take notice.

Job openings keep breaking records.

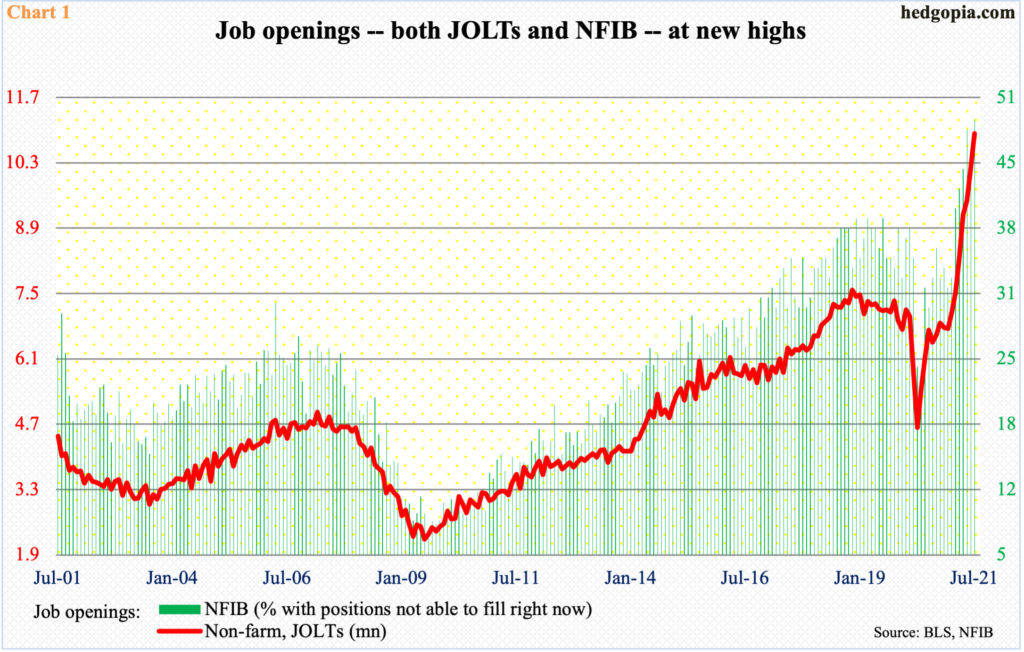

In July, non-farm openings jumped 749,000 month-over-month to 10.9 million, having come on the heels of a 702,000 increase in June. July’s was the fourth straight monthly record. From the post-pandemic low of 4.6 million in April last year, openings have gone vertical.

The JOLTs survey is in line with the trend evident among small businesses. The NFIB (National Federation of Independent Business) sub-index of job openings rose three points m/m in July to 49 – a new record (Chart 1). In May last year, the metric languished at 23.

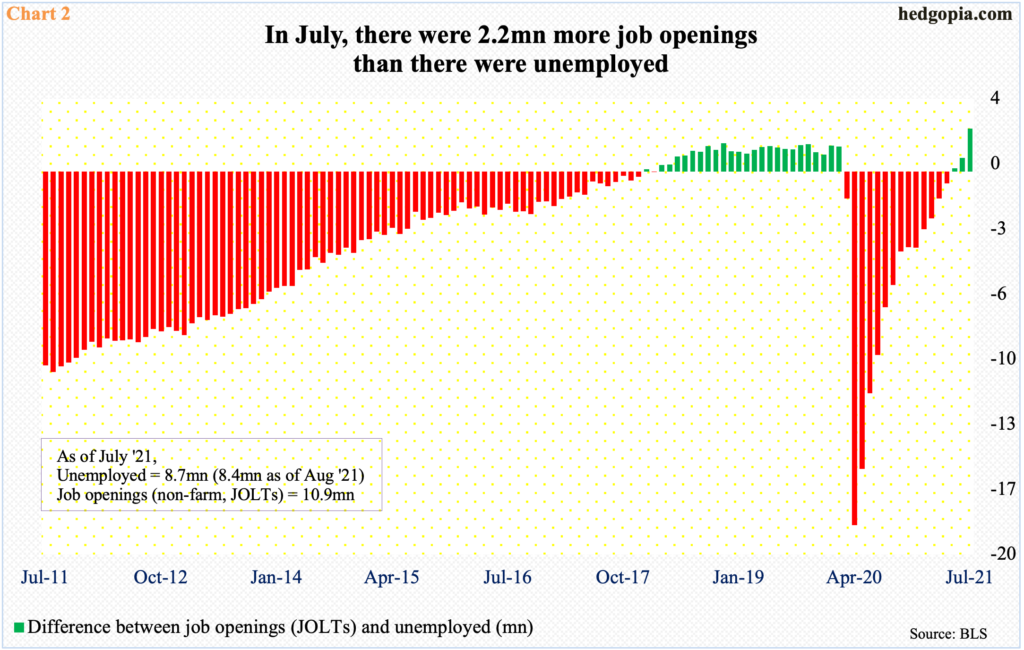

So strong is the openings trend that in July they exceeded the unemployed count by 2.2 million (Chart 2). There were 8.7 million unemployed in that month, versus the previously mentioned 10.9 million openings. (In August, the number of unemployed people fell further to 8.4 million.)

January 2018 was the first time when non-farm openings surpassed the unemployed. This persisted until Covid-19 hit. From March last year to April this year, there were more unemployed than there were jobs available. Come May through July, once again the trend reversed.

The importance of jobs cannot be overstated.

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell has consistently said that there needs to be sufficient progress on the jobs front before reducing bond purchases, let alone hiking rates.

As of August, there were still 5.3 million fewer non-farm jobs than the February 2020 record high of 152.5 million. With that said, from the April 2020 low of 130.2 million, 17 million new jobs have been created, including August’s much-weaker-than-expected 235,000.

At the annual Jackson Hole symposium in late August – that is, before the month’s jobs report was published – Powell indicated that the central bank is getting ready to taper its bond purchases by the end of the year.

The Fed buys up to $80 billion in treasury notes and bonds and $40 billion in mortgage-backed securities every month. It is sitting on $8.3 trillion in assets, nearly twice what it held in March last year.

The FOMC meets on 21-22 this month. It is now entirely possible that, given August was weak, members would like to see September’s jobs report before they decide on a timetable for tapering. The doves in particular have absolutely disregarded the prevailing trend in consumer inflation and that should continue.

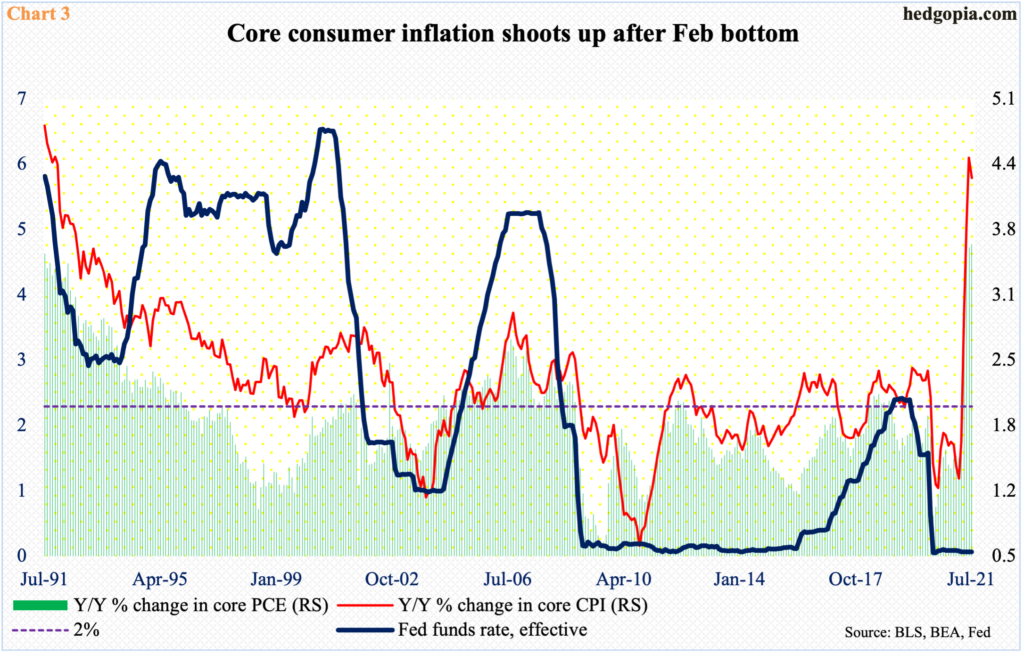

Of late, inflation has perked up. In July, core PCE jumped 3.6 percent year-over-year – the steepest rise since May 1991 – while core CPI surged 4.3 percent y/y, with June’s 4.5 percent highest since November 1991 (Chart 3).

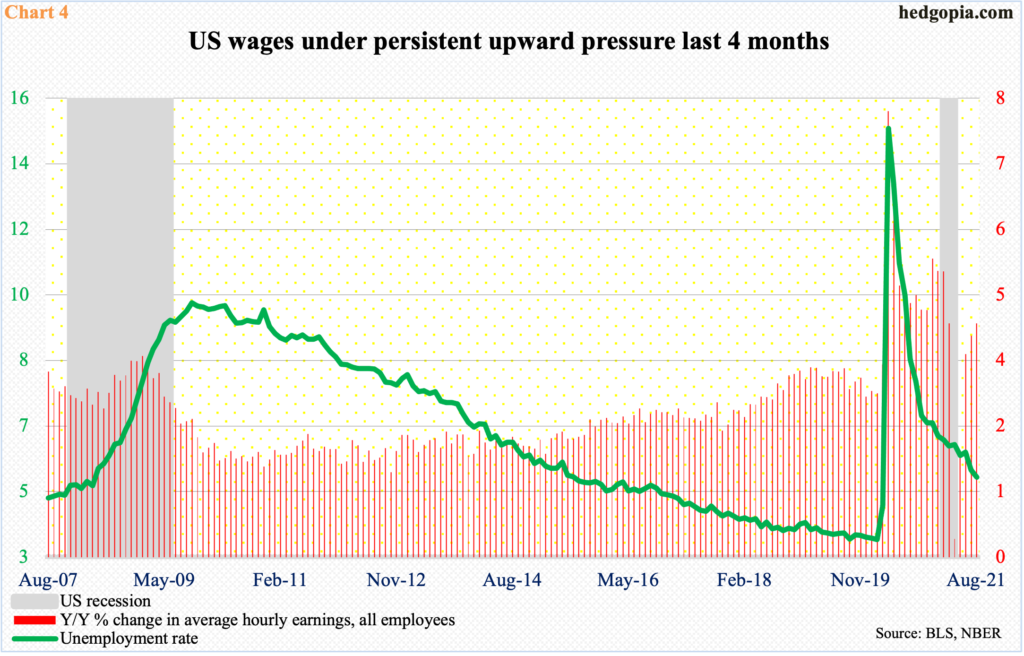

The other dynamic in this jobs-versus-inflation debate is wage growth, which in all probability should increasingly begin to get more attention.

In August, the average hourly earnings of US employees grew at a rate of 4.3 percent y/y. This is steep, although it looks less so because of an anomaly in the second quarter last year when the metric shot up thanks to government stimulus. The pace of wage growth has accelerated in the past four months.

Here is the thing. If the unemployment rate continues lower – toward the pre-pandemic low of 3.48 percent in February last year – there are decent odds the red bars in Chart 4 continue higher. Wage growth is sticky. It is hard to roll back a pay raise. Not particularly when there are nearly 11 million unfilled jobs and the bargaining power has swung from business to labor.

Thanks for reading!