The US is a credit-reliant economy. Many Americans tap credit cards to even cover essential living expenses. In June, revolving credit shot up 11.2 percent year-over-year to $1.26 trillion – barely under May’s record high. Interest rates on credit cards, in the meantime, have gone up 600 basis points in the last five quarters to 20.7 percent. This is a wrong combination.

In June, total consumer credit hit a new high. At just under $5 trillion, it grew 5.7 percent y/y. In April last year, it grew as high as 10 percent, so this represents deceleration from that pace.

That said, on an absolute basis, June added $271 billion from a year ago. And that is a lot, considering nominal GDP increased by $1.6 trillion in the June quarter from the corresponding period last year. Consumers are doing the heavy lifting.

Within consumer credit, revolving is growing much faster than non-revolving. Revolving credit is a committed loan facility allowing a borrower to borrow up to a limit; credit cards and personal lines of credit are the best examples. In non-revolving, on the other hand, once a line of credit is paid down, the account is closed; student and auto loans, and home mortgage are examples of non-revolving credit.

In June, revolving jumped 11.2 percent y/y to $1.26 trillion, while non-revolving grew four percent y/y to $3.73 trillion. In January last year, they both had similar growth rates – 9.4 percent and 8.6 percent respectively. Then they diverged, with revolving sharply shifting up and non-revolving shifting down (Chart 1).

Revolving began to pick up steam even as the Federal Reserve was entering a tightening mode. In March, it began to raise the fed funds rate, which had been left languishing between zero and 25 basis points for two years. In July, the central bank raised the benchmark interest rates by 25 basis points to a range of 525 basis points to 550 basis points. It is possible they raise one more time before leaving the rates at a higher plateau longer than currently priced in.

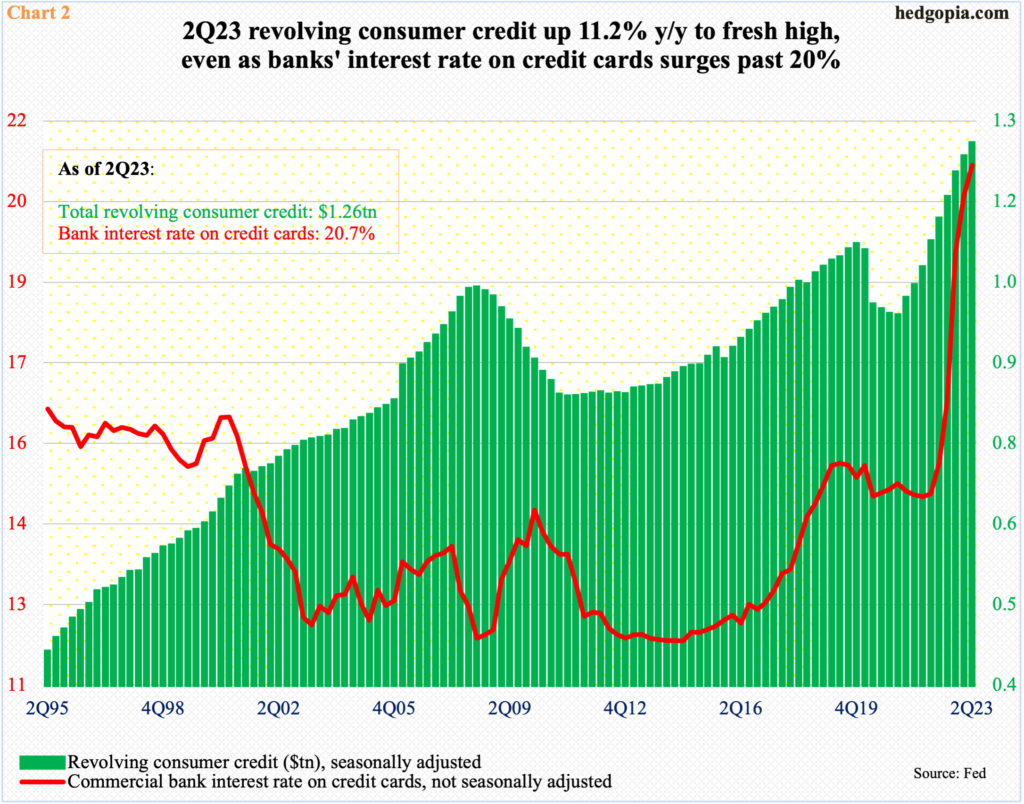

The Fed’s aggressive tightening posture is reflected in the rates consumers pay on their credit cards. In 2Q23, commercial banks’ interest rate on credit cards stood at 20.7 percent, which is the highest it has ever been going back to 1994.

The red line in Chart 2 has gone parabolic in the last five quarters, as the Fed’s tightening campaign took off and as credit card issuers passed along the higher rates. In 1Q22, these borrowers were paying 14.6 percent. It is hardly a right combination – rising debt at a time of rising rates. This has to come back to haunt consumer spending in the quarters ahead.

Thanks for reading!