Negative interest rates have been in the headlines for a while now. Since Janet Yellen’s, Fed chair, Congressional testimony last week, it has been doing so with increasing frequency.

Does the Fed even have the legal authority to use negative rates? Ms. Yellen told Congress she was not aware of any law that prevented the bank from doing so, but at the same time hedged by saying they have not completely researched whether that would be legal.

Post-financial crisis, major central banks tried zero interest-rate policy (ZIRP). Then they tried quantitative easing (QE). With a dubious progress report, some have now waded into negative interest rate policy (NIRP).

The idea is of course to weaken the currency, ignite inflation, force companies and individuals to get on the risk curve, and consume.

Despite NIRP, the Swiss franc remains relatively strong. In Denmark, however, inflows did stop, enabling that nation to maintain its peg to the euro. The ECB instituted its in 2014, and has not had much success in pushing up inflation, but the euro is weaker by nearly 20 percent. Japan just introduced its in January.

Here in the U.S., after three iterations of QE and nearly seven years of ZIRP, economic growth continues to be sub-par. Post-Great Recession, real GDP has averaged growth of 2.1 percent, versus 3.2 percent going all the way back to 2Q47.

Outside the U.S., the ECB and Japan having to move to negative deposit rates is perhaps tacit admission on their part that QE has limitations. Although it did prove to be an effective tool in generating asset inflation. Notice how well the S&P 500 index tracked U.S. QE (Chart 1).

Regardless, when the next downturn hits, for a central bank that is essentially sitting with an empty monetary tool box, negative interest rates – legality aside – is likely one of the tools the Fed will consider.

There is nearly $2.4 trillion in excess reserves banks have stashed at the Fed earning 0.5 percent interest. In Chart 2, the red line simply followed the green line higher. If these banks are forced to pay interest on these reserves, they would be tempted into loaning out these funds. Consumption and investment go up, and things will be all back to normal. A nirvana! That is the theory.

But how likely is this scenario? Of course there is no precedent. Even outside the U.S., there is only a brief history of negative rates. So here is another way to look at this.

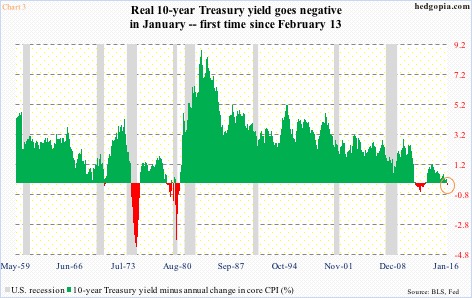

The 10-year Treasury yield just went negative in January. In Chart 3, annual change in core CPI is used. In January, the 10-year yielded 2.09 percent and core CPI rose 2.21 percent year-over-year. The 10-year yield has since dropped to 1.74 percent, so on a real basis it has gone deeper into negative territory.

A couple of observations on this.

First, going back nearly five decades, covering eight recessions, real negative yields are a rare phenomenon. Second, more often than not, they have accompanied contraction in the economy. But what is the impact on consumption/investment?

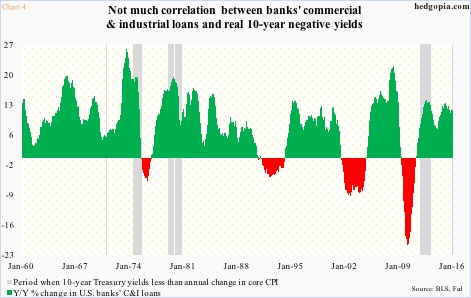

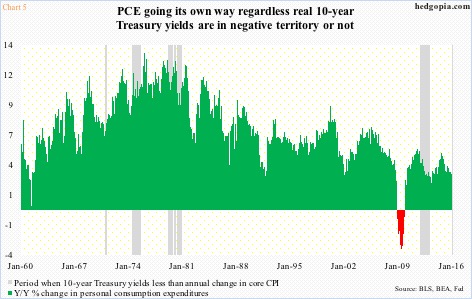

In Charts 4 and 5, the gray bars represent periods in which core CPI is higher than the 10-year Treasury yield. Against this is plotted year-over-year percent change in U.S. banks’ commercial & industrial loans in Chart 4, and y/y percent change in personal consumption expenditures in Chart 5.

There is not much correlation.

In Chart 4, in 1979 and 2011-2012, loan growth accelerated during periods of negative real yields. Not so in the other four occasions. In fact, in 1975, the gray bar was succeeded by contraction in loan growth.

The impact of negative real yields on consumption is even less evident (Chart 5). Contraction in PCE is rare to begin with. In the chart, the only time PCE contracted was during Great Recession. But the bigger takeaway is PCE going its own way regardless real yields are negative or not.

Stanley Fischer, Fed vice chair, probably has a point when he said the other day the Fed is looking at negative rates but has no plans to use them.

Thanks for reading!