- U.S. oil-related layoffs so far subdued

- Not surprising given ~80% rise in crude production past five-plus years

- Current production level problematic given inventory spike and downward pressure on crude price

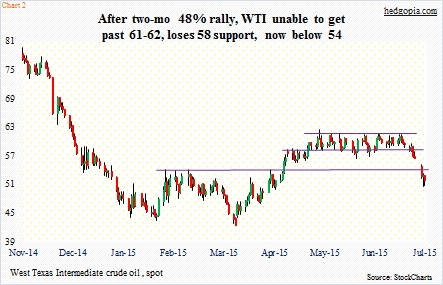

The spot West Texas Intermediate crude has gone through a lot in the past four months. After suffering a 61-percent collapse between June last year and March this year, it shot up 48 percent from that low in the next seven weeks. The sharp recovery in price has probably impacted oil companies’ decision to lay off employees – or a lack thereof. In recent sessions, the WTI has once again come under pressure. The question is, how might this impact oil jobs going forward?

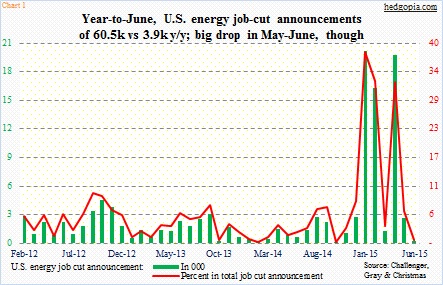

As oil peaked a year ago, oil companies initially held off on laying off employees. Energy job cuts only spiked in January (Chart 1). Between January and April, the sector announced 57,600 job cuts. Year-to-June, job cuts have amounted to 60,500, versus 3,900 in the corresponding period last year. This is a big jump, although the pace substantially softened in May and June. Only 2,944 jobs were cut in the past two months. Stability in the price of crude probably played a role in this.

As stated previously, the WTI bottomed in the middle of March, and shot up 48 percent by early May. It then moved sideways for a month and a half – between 58 and 62. A break to the upside would probably set the crude up for another sustained move higher. But it broke down. Not only has it lost support at 58 but bulls were also not able to defend 54. The latter is where the WTI broke out of in the middle of April (Chart 2). The breakdown has potential to be important.

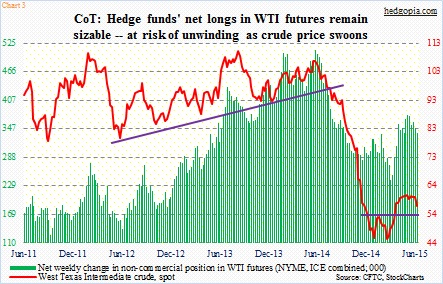

Late March, non-commercials were net long 241,000 contracts in WTI futures; in the next couple of months, this rose to 376,000 (Chart 3). These traders rode the crude rally in near perfection. Since the May high, they have reduced exposure by 10 percent, but holdings remain sizable. (In the chart, WTI price is as of last week.) For reference, around the time oil peaked last year, non-commercials were net long 510,000 contracts, which then dropped all the way to the March low. Once again, they timed it well. Now that the crude has broken support, these holdings are probably vulnerable. In a worse-case scenario, it can act as a self-fulfilling prophecy – unwinding of net longs forcing more unwinding. Technically, on a weekly basis, spot WTI has room to go lower.

Are oil jobs at risk then?

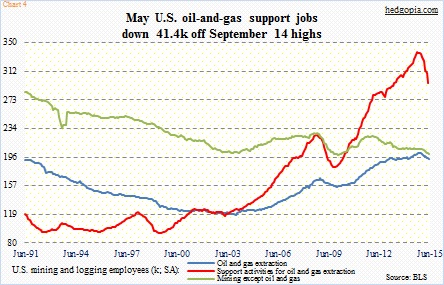

Chart 4 puts into perspective the number of jobs lost since the peak in price last year.

In October 2009, oil-and-gas support jobs bottomed at 182,200 and by last September had surged 85 percent to 337,600. Since that peak until May, there are 41,400 fewer jobs. Similarly, since the high last October, oil-and-gas-extraction jobs have shrunk by 8,300. Job losses have been subdued – considering how steep the red line has been the last five-plus years. This, however, in and of itself may not necessarily mean more layoffs are on the horizon.

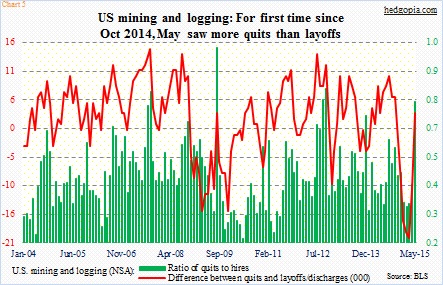

As is the case with job-cut announcements, improvement can be noticed elsewhere. Chart 5 uses the Department of Labor’s JOLTS survey in mining and logging. In May, the ratio of quits to hires was the highest since October 2012. Plus, the red line, which calculates the difference between quits and layoffs/discharges went positive for the first time since last October. People are willing to quit – a sign of confidence.

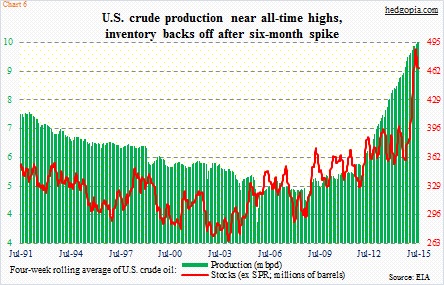

The reason? There is no letup in production. Back in October 2009, the U.S. produced 5.4 million barrels per day in crude oil. During the July 3rd week, this stood at 9.6 mbpd, near the all-time high of 9.61 mbpd a month ago (Chart 6). There is a reason for the spike in the red line on the right side of Chart 4.

These jobs are probably not at risk at present time. Risk will rise if production declines. In this regard, both inventory and oil price are data points worth paying attention to. As seen in Chart 6, toward the end of September last year, crude inventory was 357 million barrels. In the latest week, this stood at 466 million barrels! The longer production maintains the status quo, the higher the odds that inventory rises. This will then end up putting downward pressure on the price. And the longer price stays low, the higher the incentive for companies to cut back on production – a perfect scenario in which jobs will be at risk.

Thanks for reading!