Market participants have no clue how to read Wednesday’s FOMC minutes. The latter failed to settle the debate as to whether or not the Federal Reserve will move in September. Treasury bonds are acting as if the message was dovish – meaning September is off table. But equities – particularly emerging markets – do not concur.

Overall, the message probably leans dovish, but when it is all said and done, a rate-hike decision probably depends on what the Fed decides to focus on.

The Fed has a dual mandate: employment and price stability.

If it decides to focus on jobs, it is easy to rationalize a rate hike. GDP growth is subdued but probably not low enough to deserve a zero interest-rate policy. At the same time, with the benefit of hindsight, the Fed was in a much better position to move early this year. In the last three months of 2014, non-farm payroll averaged 324,000, and capacity utilization 78.8 percent. The last three months through July, job growth has weakened to a monthly average of 235,000, and utilization 77.8.

With that said, if the Fed is looking for a reason to fill its monetary quiver with arrows, then a focus on jobs provides the best excuse. Stagnant wages and inflation do not.

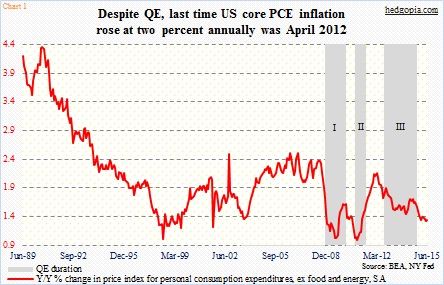

The month before QE1 began in December 2008, the price index for core personal consumption expenditures rose at an annual rate of 1.68 percent. After three iterations of QE, the last time this measure of inflation managed to rise at two percent annually was April 2012. In June, it increased at 1.29 percent (Chart 1).

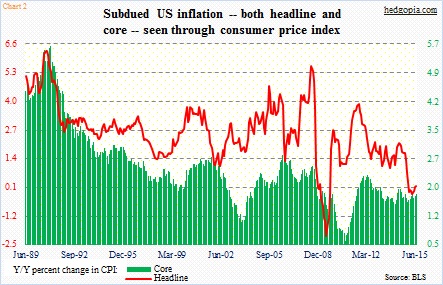

The consumer price index is running a little hotter, but even there the story is the same – it is running below the Fed’s desired rate of two percent (Chart 2). In July, core CPI rose 1.8 percent annually – a sub-two percent reading for 14 consecutive months. Due to the collapse in oil, headline CPI only grew 0.2 percent in July and 0.1 percent in June, after five straight negative readings before that.

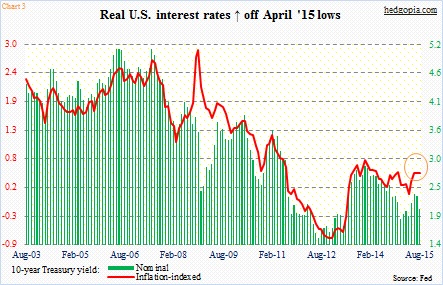

This only complicates things. Since inflation, as well as inflation expectations, are low, real interest rates are itching up. This is easier to see in Chart 3. In it, the 10-year Treasury yield has been pitted against its inflation-indexed cousin.

Treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPS) are paid a real interest rate. They earn a fixed rate of interest, like other Treasury bonds; in addition, the principal value is adjusted for inflation. In April this year, the 10-year yield on TIPS fell to as low as 0.08 percent, and has since risen to 0.5 percent – for a slight divergence (circle in Chart 3).

Viewed another way, on a real basis, the market is already tighter.

The Fed is in a box. If it moves come September, it would have completely tuned out what is transpiring on the inflation front, and the outlook thereof. Forget the fact that emerging-market currencies are already suffering side-effects of last week’s renminbi devaluation. And forget the fact that U.S. real interest rates have already tightened.

Thanks for reading!