- Debtors prefer inflation; the more the better

- Fed, ECB and BoJ yearning for higher inflation, but latter is no-show

- Low inflation gives Fed more flexibility when to hike rates, which has investment implications

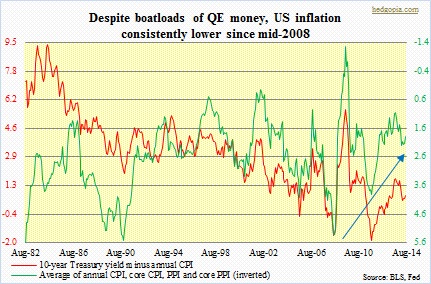

There is no shortage of issues that can potentially keep central bankers like Janet Yellen, Mario Draghi and Haruhiko Kuroda up at night. In chairwoman Yellen’s case they probably range from impact of QE unwinding on the markets/economy, how/when to eventually unwind the Fed’s bloated balance sheet, formation of asset bubbles because of the Fed policy of perpetual cheap financing, market reaction to first hike of the fed funds rate, etc. Right here and now, though, there is one that probably trumps them all, and it is one that is equally cherished/feared by all three. And that is the inflation-deflation dynamics. What if inflation is a no-show? The Fed, ECB and BoJ all are aiming for inflation in the two-percent range, but not getting it. As can be seen in the adjacent chart, since mid-2008, inflation in the U.S. has been trending lower. The chart shows an average of the CPI, core CPI, PPI and core PPI. But whether we look at the CPI, the PCE price index, or the GDP deflator, the picture is the same. The trend is down. One can argue if these indices correctly reflect the level of inflation out there. But we can only play the hand we are dealt. Here is the irony: the trillions of dollars these bankers (planners?) have created over the years have so far been unable to fan the flames of inflation.

There is no shortage of issues that can potentially keep central bankers like Janet Yellen, Mario Draghi and Haruhiko Kuroda up at night. In chairwoman Yellen’s case they probably range from impact of QE unwinding on the markets/economy, how/when to eventually unwind the Fed’s bloated balance sheet, formation of asset bubbles because of the Fed policy of perpetual cheap financing, market reaction to first hike of the fed funds rate, etc. Right here and now, though, there is one that probably trumps them all, and it is one that is equally cherished/feared by all three. And that is the inflation-deflation dynamics. What if inflation is a no-show? The Fed, ECB and BoJ all are aiming for inflation in the two-percent range, but not getting it. As can be seen in the adjacent chart, since mid-2008, inflation in the U.S. has been trending lower. The chart shows an average of the CPI, core CPI, PPI and core PPI. But whether we look at the CPI, the PCE price index, or the GDP deflator, the picture is the same. The trend is down. One can argue if these indices correctly reflect the level of inflation out there. But we can only play the hand we are dealt. Here is the irony: the trillions of dollars these bankers (planners?) have created over the years have so far been unable to fan the flames of inflation.

Come to think of it. Why would a central banker want inflation? To be fair, they are not pining for runaway inflation. A two-percent goal falls within their price stability mandate. Two points merit attention. Firstly, they have dropped plenty of hints that in the present circumstances they would be comfortable with higher than their stated goal of two percent. Secondly, history time and again has taught us that once the inflation genie is out of the bottle, forcing it back in comes with cost. Back in 1981 Paul Volcker had to raise the fed funds rate all the way up to 20 percent (no, not a typo) to bring the prevailing stagflation under control (CPI peaked at a tad under 15 percent in March of 1980). This is not to say that there currently are ingredients in place to ignite that kind of inflation. But the fact that these bankers are yearning for more is symptomatic of a problem shared by all three. DEBT. In Japan, central government debt as a percent of GDP is over 200 percent. In the U.S., federal debt as a percent of GDP is over 100 percent. In the euro zone, comprised of 18 sovereigns, this ratio varies from one country to another, but the problem is more acute in the southern region. The sovereign debt crisis has been affecting the euro zone since early 2009.

Come to think of it. Why would a central banker want inflation? To be fair, they are not pining for runaway inflation. A two-percent goal falls within their price stability mandate. Two points merit attention. Firstly, they have dropped plenty of hints that in the present circumstances they would be comfortable with higher than their stated goal of two percent. Secondly, history time and again has taught us that once the inflation genie is out of the bottle, forcing it back in comes with cost. Back in 1981 Paul Volcker had to raise the fed funds rate all the way up to 20 percent (no, not a typo) to bring the prevailing stagflation under control (CPI peaked at a tad under 15 percent in March of 1980). This is not to say that there currently are ingredients in place to ignite that kind of inflation. But the fact that these bankers are yearning for more is symptomatic of a problem shared by all three. DEBT. In Japan, central government debt as a percent of GDP is over 200 percent. In the U.S., federal debt as a percent of GDP is over 100 percent. In the euro zone, comprised of 18 sovereigns, this ratio varies from one country to another, but the problem is more acute in the southern region. The sovereign debt crisis has been affecting the euro zone since early 2009.

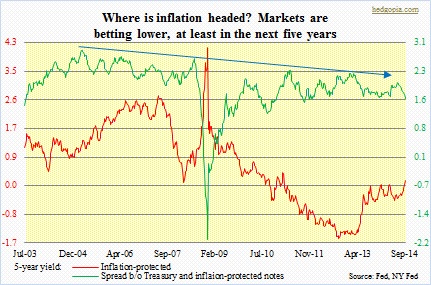

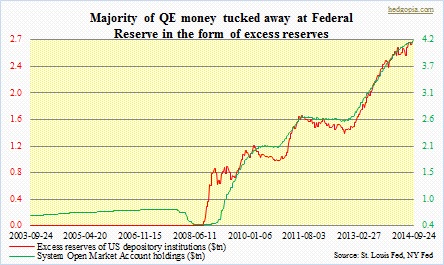

Hence the prevailing strategy adopted by these central banks – push nominal interest rates down toward zero so debt-service is eased, and try to ignite inflation so that debt is gradually inflated away. In a higher inflation environment, debtors benefit. Debt is worth less as the day goes by. By default, deflation ends up raising real interest rates, which is fine from a creditor’s perspective, but not a debtor. The U.S. is a debtor nation – up to its gills – and we need inflation. So does Japan. So does the euro zone. In due course, China would start wishing for the same. From the U.S.’s perspective, the chart on top (first chart) is not welcome. Even more worrying is the chart above. The green line seeks to decipher where inflation is headed – or at least how the markets think where it is headed. A breakeven rate is calculated by subtracting five-year TIPS from five-year Treasury notes. It is a rough approximation of how bond vigilantes are pricing in five-year inflation. For nearly 10 years now, the trend has been decidedly lower, and has particularly weakened since mid-July. Not what these bankers would like to see.

This will have investment implications. Low inflation raises the odds that the Fed will have the luxury of staying accommodative longer. Lack of pricing power is also a sign of the times in that this points to demand constraints – probably means banks’ excess reserves at the Fed stay put. If there is not much inflation, long bonds will have their share of bids. And financials rallying on hopes of a steep yield curve will have their share of disappointment. Last but not the least, the U.S. dollar is in the midst of a furious rally in expectation of higher interest rates – hence higher spreads vis a vis other currencies – putting downward pressure on imported goods. Once again, low, or lower, inflation gives the Fed more flexibility on when to start hiking rates. Thus the potential for disappointment as regards to investment themes betting on higher interest rates sooner than later.