Intra-meeting Tuesday, the Fed delivered a 50-basis-point reduction in the fed funds rate. Stocks yawned, gold rallied and the 10-year T-yield fell to a new low. What gives?

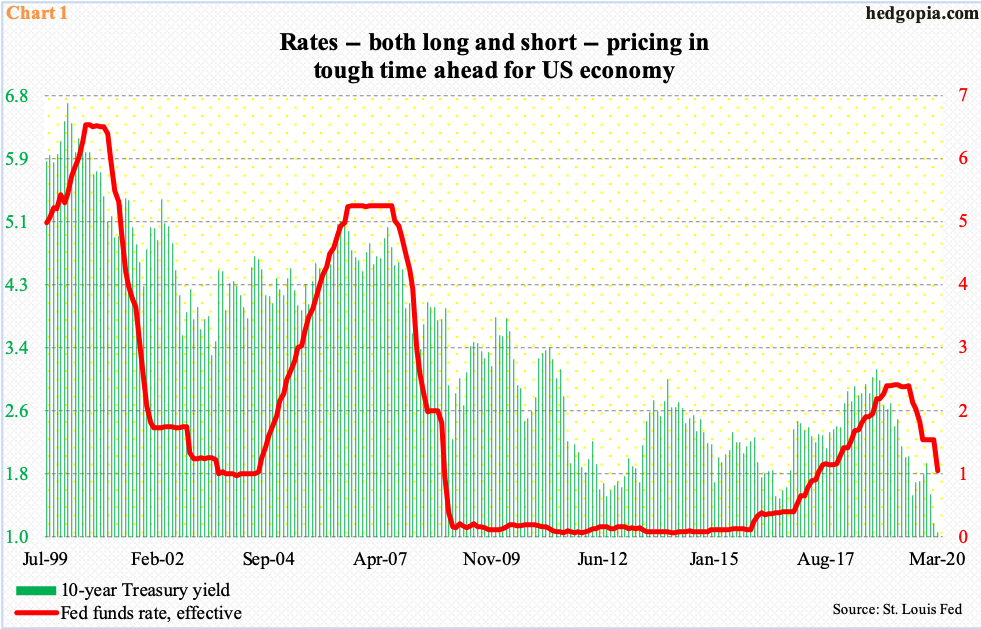

Emergency cuts are rare. As are 50-basis-point cuts. Intra-meeting Tuesday, the Fed engineered one, lowering the fed funds rate to a range of 100 to 125 basis points (Chart 1).

Prior to this, the last 50-basis-point cut took place in October 2008 – in the midst of the severest financial crisis since Great Depression. Back then, this was followed by another cut of the same magnitude later that month, to one percent; by mid-December, rates were pushed to a range of zero to 25 basis points. This time around, markets are betting there will be one more 25-basis-point cut by the end of this year. At this pace, it would not be long before the Fed runs out of this conventional ammunition.

It would not be an exaggeration to state that the Fed is held hostage by the financial markets. This has pretty much been the case since Alan Greenspan took the helm of the central bank in 1987. His successors – Ben Bernanke, Janet Yellen and now Jerome Powell – have followed on his footsteps. Hence the so-called Fed put. Every now and then, stocks throw a temper tantrum, and the Fed is forced to hand out monetary morphine.

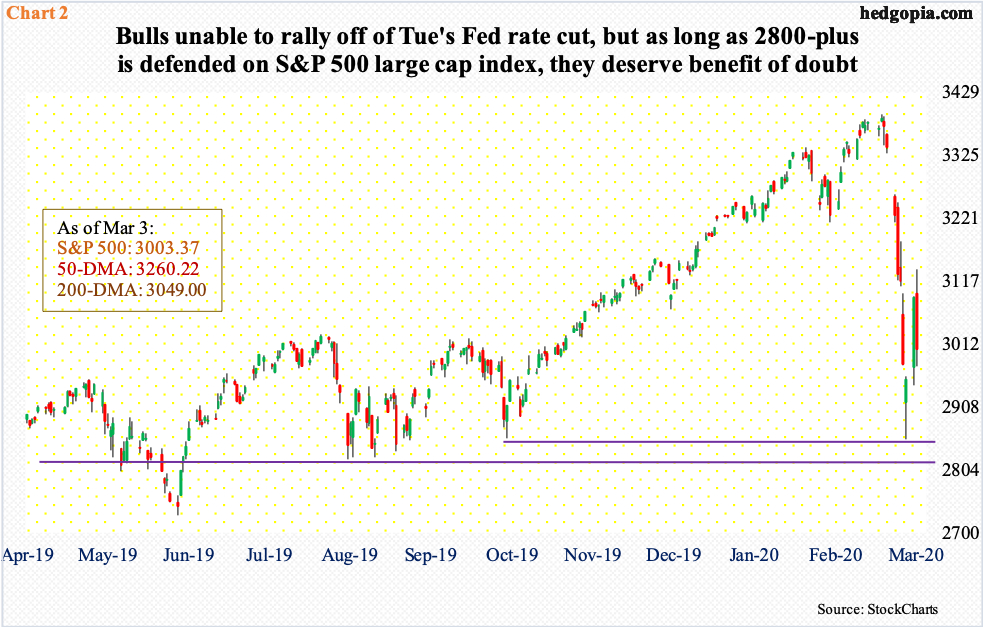

In December 2018, the Fed hiked the policy rate by one-quarter point – its fourth that year – and said it expects to raise two more times in 2019. Stocks, already under pressure, were clearly not happy, beginning another leg lower. Soon, the Fed’s message shifted from hawkish to dovish. Come 2019, it ended up lowering the benchmark rate by 75 basis points, and the S&P 500 large cap index shot up nearly 29 percent (Chart 2).

Tuesday, stocks’ reaction function was different. In a volatile session, the S&P 500 gave back 2.8 percent. Gold rallied 3.1 percent. The 10-year Treasury yield made a new record low of 0.91 percent intraday before ending the session down eight basis points to 1.01 percent (Chart 1). This is clearly not the kind of reaction the Fed wanted to see out of these assets.

There are a few possibilities why things may have unfolded this way.

(1) Stocks are essentially saying this time it is different. A rate cut is unlikely to properly address the problems stemming from the Covid-19. Arguably, by moving intra-meeting, the Fed injected a little bit of panic into the markets. In other words, just as the Fed is lending a helping hand, it is also laying bare of a toolbox that is running empty. (2) After last week’s rout, major US equity indices managed to defend important support, but they need more time to repair the damage that is already done. As long as 2800-plus is not breached, bulls deserve the benefit of the doubt (Chart 2). (3) Now that the Fed caved in, stocks want more on the fiscal side. (4) They are not sure how all this will end up impacting earnings.

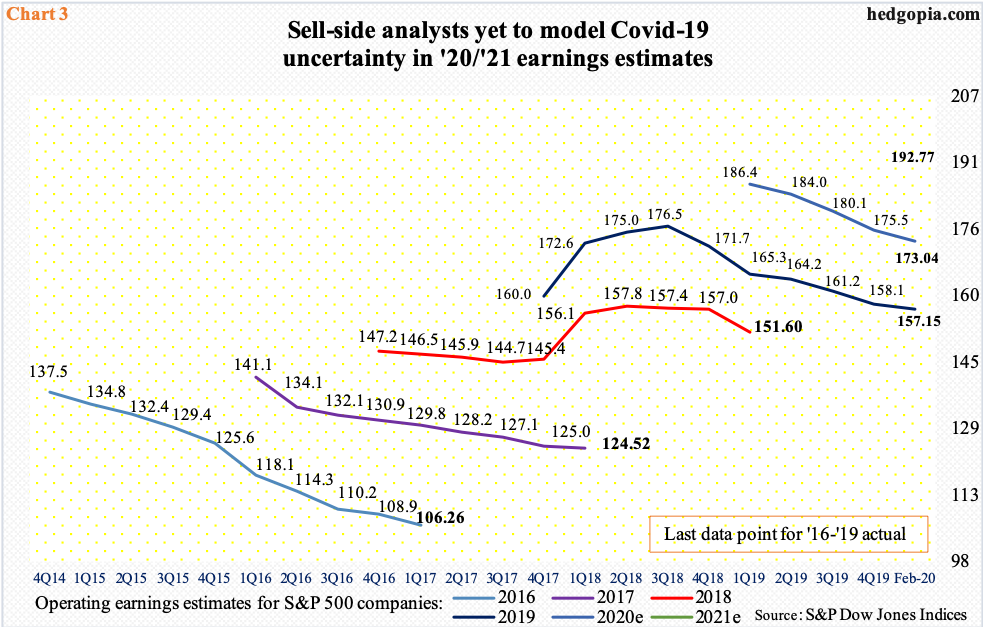

As relates to earnings, the new coronavirus was first encountered in Wuhan, China, last December. Shortly afterwards, commodities such as copper and crude oil peaked, as did the 10-year T-yield. Stocks, on the other hand, kept rising, until last week’s reversal. The sell-side has not even begun to model in an all-but-certain hit to S&P 500 operating earnings due to coronavirus-related dislocations in the global economy.

As of February 28, these analysts expected $173.04 this year, up 10.1 percent from last year. Next year, they expect $192.77, up another 11.4 percent. This reflects pie-in-the-sky optimism, and stocks, realizing that, could very well be rerating themselves. Or, (2) and (3) above could be at play. What major central banks globally – the Fed in particular – would not want is (1), as this would usher in a totally uncharted territory.

Thanks for reading!