- Market expectations for rate hike next year runs risk of disappointment

- With monetary quiver nearly empty, Fed very much focused on wealth effect

- Job even more difficult, given adverse effects of cheap money beginning to loom

Markets are sending mixed messages.

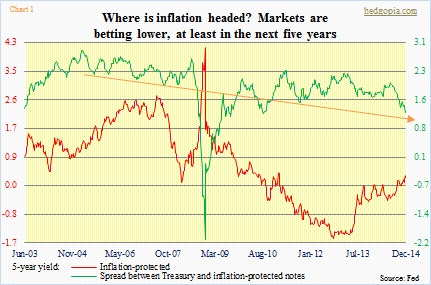

On the one hand, they have priced in a rate hike (by the Fed) next year, on the other have pushed five-year inflation expectations to the lowest since September 2010 (Chart 1). That green line has been on a downward slope for some time now, and cannot seem to catch a break. Some 75-percent of the economists surveyed expect the Fed to remove the phrase “considerable period” from the FOMC minutes later today. As if that really matters.

Let us hypothesize that the Fed does indeed remove the phrase or replaces it with something else, does that in and of itself indicate that they are ready to move come next year? “Considerable period” may stay or go. Not a big deal. The Fed may as well oblige the markets. Or, they may not. Who knows? But the odds of them obliging to markets’ demand for higher rates next year are low. Even if “considerable period” is done away with, rate hike next year is not a slam dunk.

The argument goes like this. U.S. economic data have gotten better. Which they have, by the way, versus other major economies. And if ever there was an opportunity for the Fed to begin tightening, this is it. Well, not quite. Here are two counterarguments.

First, strength in the data today does not guarantee a repeat tomorrow. This is not a normal cycle we are dealing with. There is a reason why central banks are in panic mode. Ex-U.S., things are slowing down globally. Oil is in crash mode, and may very well be pointing to a global slowdown next year.

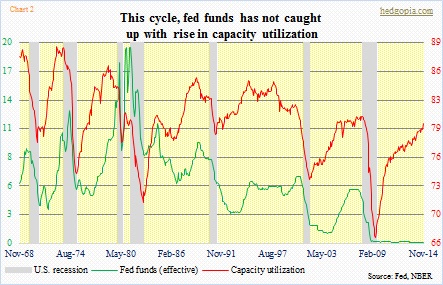

Secondly, if the Fed solely focused on data, they probably would have already begun a process of tightening, however tentative. Their quiver is running out of arrows. They know it. And it would make sense to replenish when the going is good. The Fed funds rate has been zero-bound for over five years now, even as the capacity utilization has risen from nearly 67 to 80. Chart 2 shows the unusual divergence between the green and red lines in the current cycle.

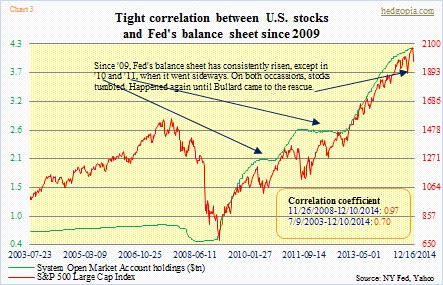

Simply put, their hands are tied. Former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke made no bones about seeking to tap into the benefits of wealth effect after QE was introduced. Post-financial crisis, when the economy was trying to pull itself up by its bootstraps, this was indeed a good strategy. But sticking with it all through was not. Each time markets reacted negatively to the end of QE1/2, the Fed responded with more stimulus (Chart 3). Back in May last year in the wake of Bernanke’s taper talk, the S&P 500 quickly shed 7.5 percent. When asked during her inaugural press conference in March this year, Chair Janet Yellen suggested rates might begin to rise six months after the end of QE3. That was followed by a quick 4.5-percent drop in the S&P 500. By now, markets know how to influence the Fed.

The point is, the Fed has painted itself in a corner. Things are particularly difficult now that the adverse side effects of years of cheap money are just about beginning to come into sight. Currency, bonds, you name it, dislocation and contagion risks are there to see.

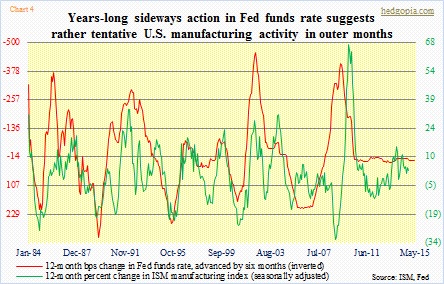

So, yes, the Fed stays put. Here is the thing. The longer the zero-bound continues, the lesser its effect. If rates fall from, let us say, three percent to two percent, borrowers are incentivized to act. In most cases, anyway. If it is 10 basis points today and 10 basis points tomorrow, where is the incentive? And that is what Chart 4 is suggesting. The Fed funds rate has gone sideways for so long there is not much incentive for that green line to move up.

Let us hope the Fed knows how to get out of this and has a plan in place. A rate rise next year is probably not what it has in mind.