In late 2014/early 2015, U.S. economic data began to either stall or decelerate.

Take capacity utilization, for instance. It peaked at 78.9 percent in November 2014, peaking before tagging 80 percent (Chart 1). The Fed funds rate was still near zero, but that was no help. Utilization was merely 75 percent this November, and has now declined for 21 consecutive months.

Here are other examples.

Real GDP jumped at an annual rate of five percent in 3Q14; this was the highest quarterly growth rate in 11 years. Corporate profits adjusted for inventory and depreciation peaked at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of $2.22 trillion in 4Q14; 3Q16 was $2.15 trillion. The NFIB small business optimism index reached a cycle high 100.3 in December 2014; November this year was 98.4.

And some more.

The University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment index reached an 11-year high 98.1 in January 2015; the latest reading (December, preliminary) is 98. Orders for non-defense capital goods ex-aircraft – proxy for business capital expenditures – reached an all-time high $70.7 billion (SAAR) in September 2014, and were $62.9 billion this October. In 2014, the economy added a monthly average of 251,000 non-farm jobs. This decelerated to 228,000 in 2015, and to 180,000 year-to-date. And on and on.

The Fed at the time obviously believed that the data was only going to get stronger, and decided to wait to begin to tighten.

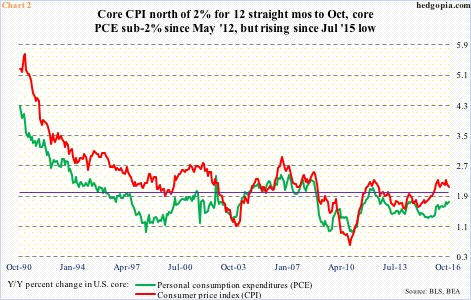

To be fair, inflation was subdued.

Annual core PCE (personal consumption expenditures) began to drop after rising at 2.03 percent in April 2012. This is the Fed’s favorite measure of consumer inflation, and has remained sub-two percent since. Likewise, between March 2013 and October 2015, core CPI (consumer price index) remained under two percent (Chart 2).

Other than this, hindsight is always 20/20, but it turns out 2014 offered a big window of opportunity, during which the Fed could have squeezed in a couple of hikes.

On Wednesday, the Fed funds target rate was raised by a quarter percent to a range of 0.5 percent to 0.75 percent. But should the Fed have gone for a 50-basis-point hike? Probably. Here is why.

December last year was the first time in more than nine years that the Fed hiked (Chart 1). At the beginning of this year, the dot plot planned on four more hikes this year. The stock market immediately went hysterical. In 15 sessions between December 29 and January 20, the S&P 500 large cap index collapsed 13 percent (Chart 3). For a Fed that believed in the virtues of wealth effect, the message was clear.

Instead of four, the Fed ended up raising just once this year. (For whatever it is worth, the dot plot is planning on three hikes next year.)

In fact, in markets versus the Fed, the former have been winning for a while. Leading up to the first iteration of quantitative easing in November 2008, U.S. stocks had been under pressure for more than a year. Since then until QE3 ended in October 2014, stocks and QE pretty much moved in tandem (Chart 4).

Taper tantrum in 2013 was another example. When in May that year, Ben Bernanke, then-Fed chief, floated the idea of gradually reducing the purchase of bonds, yields shot up, and stocks had a mini panic. Once again, the Fed backed off. QE continued.

This time around, leading up to this week’s FOMC meeting, a 25-basis-point hike was baked in, yet U.S. equity indices were hovering near all-time high.

Post-election, markets’ focus has shifted to a monetary-to-fiscal handover. President-elect Donald Trump’s emphasis on cutting taxes, pruning regulations, and investing heavily in infrastructure have raised growth hopes for next year and beyond. Markets probably would not mind a 50-basis point hike. This was the Fed’s window of opportunity.

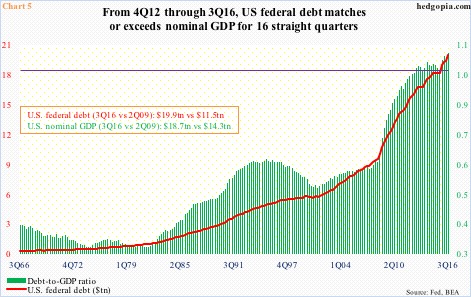

An opportunity because come next year the budget deficit and the government’s debt load are bitter facts that Republican-controlled Congress – budget hawks, in particular – will probably not remain oblivious of. The debt-to-GDP ratio in 3Q16 was 1.07 (Chart 5). This was the 16th consecutive quarter in which federal debt exceeded nominal GDP. Massive stimulus is anything but given.

In fact, in the post-meeting press conference yesterday, Ms. Yellen did mention that the economy was near full employment. In other words, the cycle is getting long in the tooth.

And the Fed’s monetary tool box is empty. When the next downturn hits – just a matter of when, not if – it has nothing in the way of conventional tools, even as the success of unconventional methods such as quantitative easing is debatable.

Thanks for reading!