On Wednesday, Powell confirmed that the fed funds rate has peaked and that the next move is lower but did not go far enough to please equity bulls drooling over prospects of a cut in March. It is an irony that the futures traders continue to expect six cuts this year. They were disappointed yesterday and will be disappointed again.

“Based on the meeting today, I would tell you that I don’t think it’s likely that the committee will reach a level of confidence by the time of the March meeting to identify March as the time to do that. But that’s to be seen.”

The above statement was made by Jerome Powell, Federal Reserve chair, during a press conference after conclusion of a two-day FOMC meeting on Wednesday. Going into the meeting, markets were on pins and needles if the Fed would start cutting in March. In the presser, Powell was adamant that this was unlikely but did suggest that rate cuts would likely begin at some point this year.

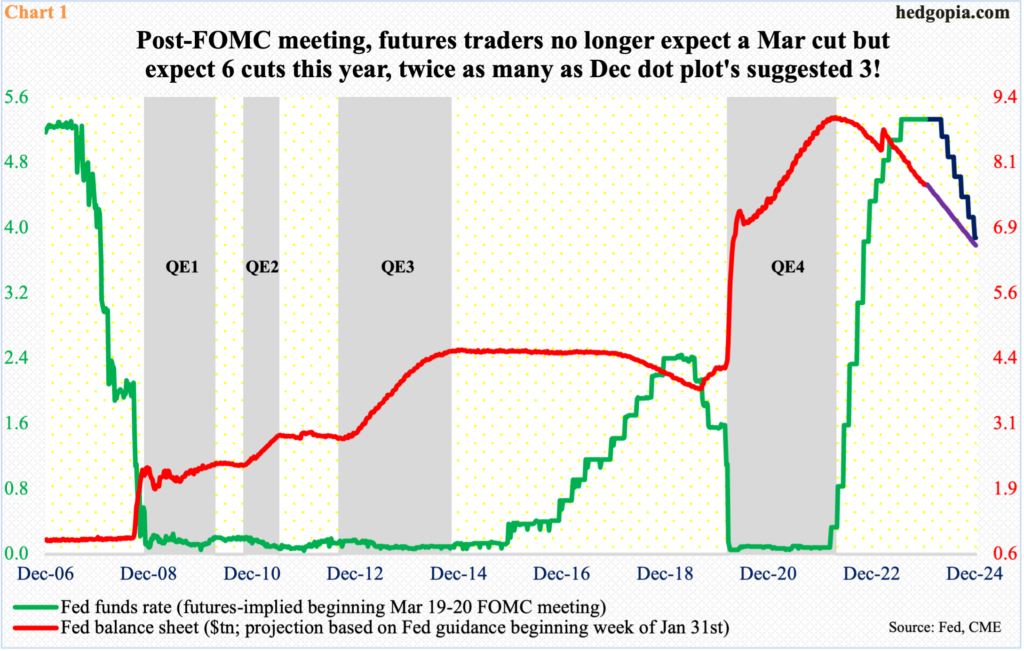

At the December meeting, the dot plot indicated there would be three 25-basis-point cuts this year, up from two at the September meeting. Three cuts would put the fed funds rate between 450 basis points and 475 basis points by the end of the year. The benchmark rates, after going sideways at a range of zero to 25 basis points for two years, were first raised in March 2022, subsequently reaching 525 basis points to 550 basis points by last July.

In the futures market, March is now off the table, with probabilities of a cut dropping to 36 percent. That said, traders are back at pricing in six cuts, expecting a cut in each of the remaining six meetings after March, ending the year between 375 basis points and 400 basis points (Chart 1). The Fed, which is also likely to tweak its current pace of balance sheet reduction, obviously does not see it that way. For the central bank to change its current posture, the three variables discussed below will have to undergo substantial changes.

Even though the fed funds rate has gone up by 525 basis points since March 2022, the economy is hanging in there. Yes, there are signs of deceleration from the heady pace earlier, but things are hardly falling apart.

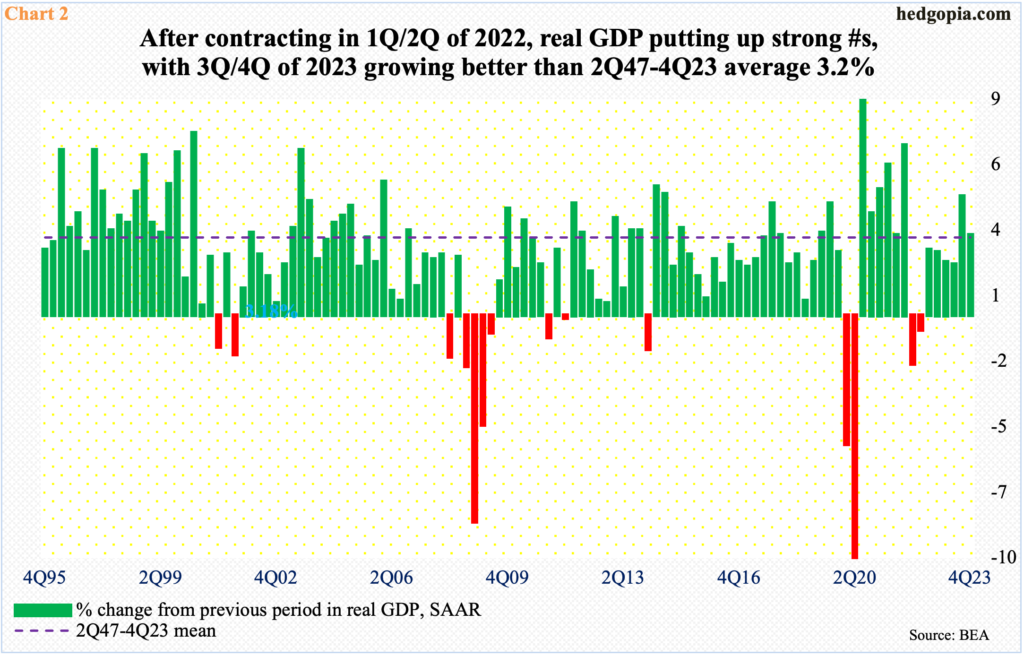

The first print showed that real GDP last quarter expanded at an annualized rate of 3.3 percent. This comes on the heels of a 4.9-percent expansion in the prior quarter. Both these rates are better than the average 3.2 percent recorded since 2Q47.

The current pace of expansion is slower than the quarters immediately after the Covid recession but is not too shabby historically. For the Fed to acquiesce to futures traders’ demands, the bars in Chart 2 need to get a lot smaller, or, worse, go negative.

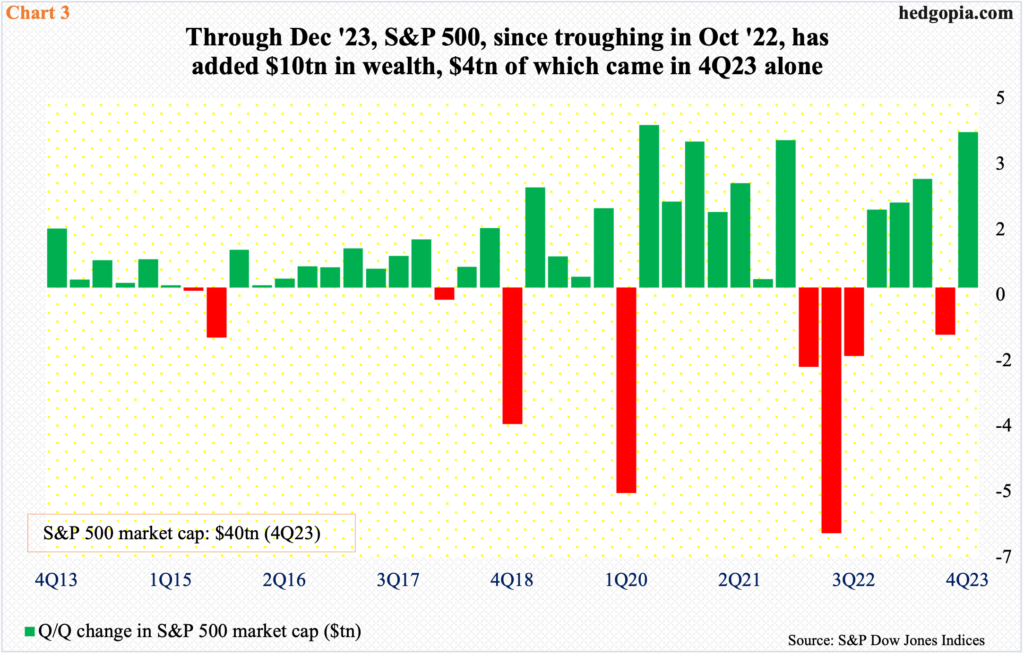

In the current circumstances, the Fed is not a big fan of the ongoing easing in the financial conditions. Equities first bottomed in October 2022 and then again last October. From October 2022 through last month, the S&P 500 has added $10 trillion in wealth, to a market cap of $40 trillion. Just from last October’s bottom, the large cap index went up by $4 trillion (Chart 3).

This is a tremendous amount of wealth creation, which has a big potential to influence consumers’ behavior through what economists call the wealth effect.

In January, the University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment index shot up 9.1 points month-over-month to 78.8, which is the highest print since July 2021. Last November, the metric stood at 61.3, with a record low 50 in June 2022.

The relentless rally in equities since late October last year has lifted consumers’ mood, and this is also reflected in retail sales, etc., not to mention the fact that Investors Intelligence’s bullish percent this week jumped 4.8 points week-over-week to 57.7 – a 133-week high, that is, since mid-July 2021.

While there is nothing wrong in investors making money in a capitalistic system, this at the present time has room to pose a risk to the Fed’s current campaign to bring inflation to its two-percent goal.

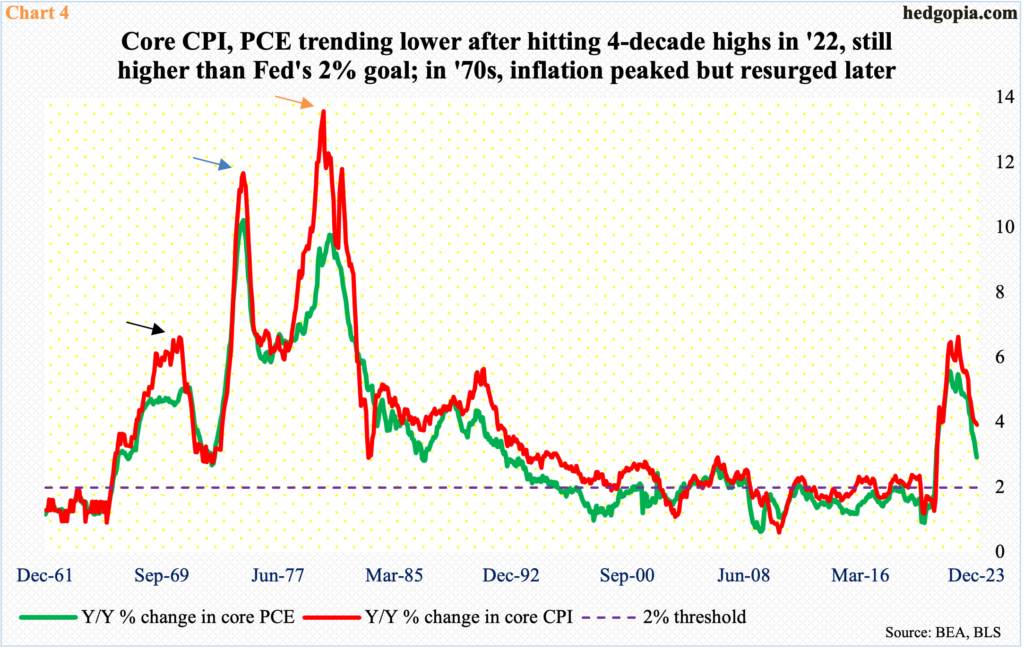

At least a few times back in the 1970s, inflation peaked, came under pressure and resurged (arrows in Chart 4). Once bitten, twice shy. The Fed obviously does not want to relive that experience.

After reaching four-decade highs in 2022, inflation is headed in the right direction. In December, core CPI and PCE respectively grew 3.9 percent and 2.9 percent from a year ago. In 2022, the two peaked at 6.6 percent and 5.6 percent in September and February, in that order. The Fed prefers core PCE, and, even on that basis, inflation remains above its target.

With this as a background, the Powell-led team would not mind a little weakness in the economy, continued disinflation, and a healthy selloff in stocks. Powell should be commended for not submitting passively to markets’ demands, as was often the case when the institution was led by Janet Yellen, Ben Bernanke and Alan Greenspan.

Thanks for reading!