Later today, markets will learn if, when it comes to the so-called Fed put, it is game as usual or winds of change are beginning to blow.

The Fed put refers to a practice of reducing interest rates to deal with downward pressure on stocks. Its existence has been officially denied, but markets believe it exists. They have a reason to. As the saying goes, if it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it probably is a duck.

The term was first coined during the Alan Greenspan era (1987-2006).

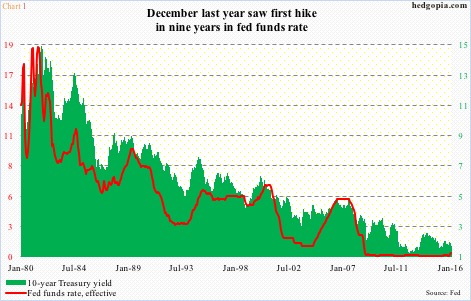

In response to the stock market crash of October 19, 1987, the Fed immediately lowered the fed funds rate. Early October that year, fed funds stood at 7.25 percent. Post-crash, it was lowered to 6.88 percent, and by February next year stood at 6.5 percent (Chart 1).

Then in 1998 the Fed acted again responding to the Long-Term Capital Management debacle. In August that year, fed funds was 5.5 percent, dropping to 4.75 percent in the next three months.

When Ben Bernanke (2006-2014) succeeded Mr. Greenspan, the Greenspan put got replaced by the Bernanke put. The quote below is from an interview Mr. Bernanke gave to CBS’ 60 Minutes in March 2009.

“And I care about Wall Street for one reason and one reason only – because what happens on Wall Street matters to Main Street.”

There you have it! It is perhaps as clear a statement as any to maybe justify the need for a put.

During the financial crisis, fed funds stood at 5.25 percent in August 2007. By December 2008, it was pushed to near zero (between zero and 25 basis points). Then came quantitative easing – not one, but three iterations over six years.

Truth be told. The problem Mr. Bernanke’s Fed faced at the time was grave. The financial system was on the brink of collapse, and the U.S. economy was falling apart. With conventional monetary tools having been spent, unconventional tools were used, such as QE.

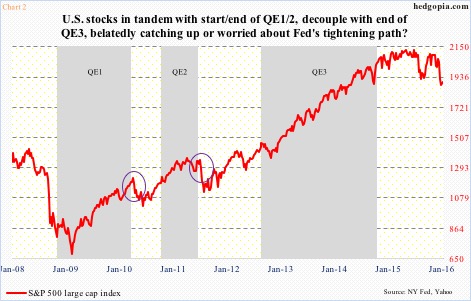

Apart from giving a jolt to the financial system and the economy, the Fed was attempting to boost equities, set wealth effect in motion, as well as get investors on the risk curve. The latter obliged, knowing a Bernanke put was alive and well (Chart 2).

In the middle of September 2014, U.S. stocks began to act like drug addicts being denied of daily dose. The Fed was on course to ending QE3 in October that year. By the middle of that month, the S&P 500 lost nearly 10 percent. Then on the 16th James Bullard, the St. Louis Fed president, told Bloomberg TV the Fed should consider delay in ending QE; he also suggested more QE. Phew! Stocks breathed a sigh of relief. Investor nerves were calmed.

Fast forward to the present, and stocks are once again acting up. Between the December 29th high and the January 20th low, the S&P 500 lost nearly 13 percent. That is in 14 sessions. As a matter of fact, at the intra-day low a week ago the October 2014 low was tested.

Persistent drop in crude oil and uncertainty surrounding yuan devaluation are among factors bothering stocks. They are also trying to figure out the path of the Fed’s tightening cycle.

In the middle of December last year, the fed funds rate was nudged higher by 25 basis points – the first hike in nine years (Chart 1). At the time, the FOMC dot plot projected four more quarter-point hikes this year, versus two expected by Mr. Market. After massive sell-offs in stocks globally, including the U.S., markets now expect only one hike this year, that too not until September.

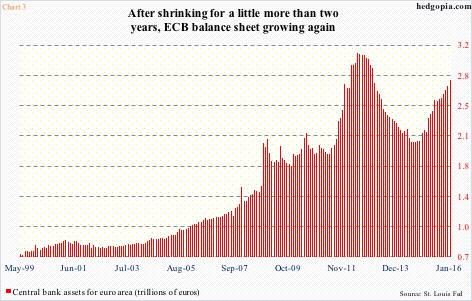

The ECB, which has been expanding its balance sheet since October 2014, sought to soothe investor nerves with talk of more stimulus (Chart 3). Early December last year, European markets were disappointed by Mario Draghi, ECB president, who was not dovish enough to live up to markets’ expectations.

Last week, Mr. Draghi hinted at more stimulus as early as March. Speaking to reporters post-governing council meeting on Thursday, he said downside risks had increased at the start of the year.

In light of this, the FOMC meeting this week is a non-event in that no policy decision will be made, and would probably be treated as such if stocks were acting normal. They are not. They are acting jittery.

Depending on what the statement reads, and suggests, at 2PM today has the potential to impact stocks’ path near-term. Markets are looking for hints – and tweaks in the language to suggest rate-hike plans have been dialed back – that a Yellen put has their backing. Would Ms. Yellen oblige or decide it was time to end the hand-holding? The answer has immense implications for assets across the board, not the least of which is stocks.

Thanks for reading!