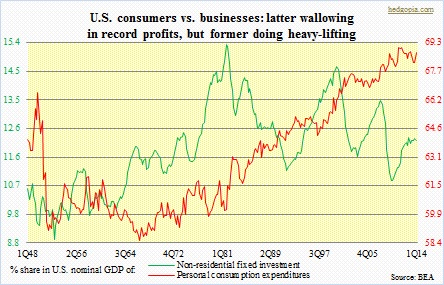

The 1Q14 GDP print was a shocker, to say the least! Real GDP inched up a mere 0.1 percent SAAR, versus consensus expectations of 1.2-percent expansion. Sure, it is the advance estimate, with two more still to come. Sure it likely will be revised higher, as March economic data have strengthened vs. the first two months of the year. But deceleration is evident. The economy expanded 3.4 percent in 2H13. Perhaps even more important, ‘personal consumption expenditures’ contributed 2.04 percent in ‘GDP percent change’, vs. -0.25 percent from ‘non-residential fixed investment’.

The 1Q14 GDP print was a shocker, to say the least! Real GDP inched up a mere 0.1 percent SAAR, versus consensus expectations of 1.2-percent expansion. Sure, it is the advance estimate, with two more still to come. Sure it likely will be revised higher, as March economic data have strengthened vs. the first two months of the year. But deceleration is evident. The economy expanded 3.4 percent in 2H13. Perhaps even more important, ‘personal consumption expenditures’ contributed 2.04 percent in ‘GDP percent change’, vs. -0.25 percent from ‘non-residential fixed investment’.

What is wrong with this picture?

Consensus forecasts for the remaining three quarters this year are for the economy to vehemently snap back, with growth of over three percent in each. How realistic are these expectations? The U.S. labor force is growing at about half a percent a year. To get to three percent growth in the economy, productivity needs to be growing at 2.5 percent. Probable? This looks increasingly unlikely given the current dynamics between business investment and consumer spending.

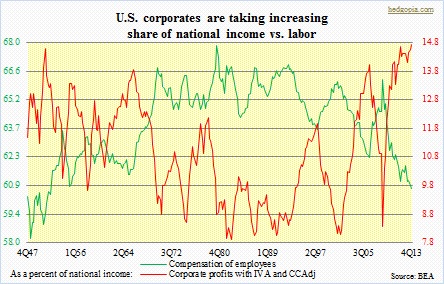

Previously, we have talked about how, despite record high margins and profits, corporations have been stingy with capital spending. The accompanying chart further shows how U.S. corporations are increasingly taking an increasing share of national income vs. labor. Yet they are cautious in spending – both capital and labor. Simplistically, a business exists to make money. If they see demand firming or expect an improving trend to sustain for years, common sense would tell us that they would make the right investments now in order to benefit later. Yet, that is not happening. There is a lack of aggressiveness on their part. One simple explanation is that they do not yet believe the improvement in the economy is sustainable and hence are awaiting another downturn before making investments. There are good arguments for that.

Previously, we have talked about how, despite record high margins and profits, corporations have been stingy with capital spending. The accompanying chart further shows how U.S. corporations are increasingly taking an increasing share of national income vs. labor. Yet they are cautious in spending – both capital and labor. Simplistically, a business exists to make money. If they see demand firming or expect an improving trend to sustain for years, common sense would tell us that they would make the right investments now in order to benefit later. Yet, that is not happening. There is a lack of aggressiveness on their part. One simple explanation is that they do not yet believe the improvement in the economy is sustainable and hence are awaiting another downturn before making investments. There are good arguments for that.

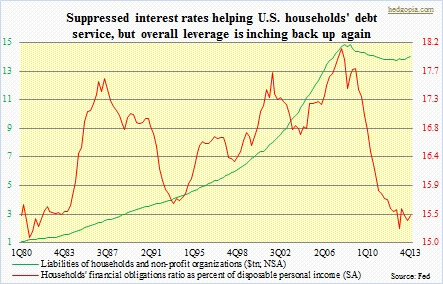

Interest rates have been artificially suppressed for too long, hence the artificial nature of end-demand. The root of the problem lies in debt, and not much progress has been made on that front. At the federal level, debt has doubled the last seven years. Post-Great Recession, households did begin a process of deleveraging, but leverage is growing again. Thanks to the Federal Reserve’s ultra-easy monetary policy, corporations have managed to mend their balance sheets; low interest rates have helped both balance sheet (debt refinancing) and income statement (low interest payments). Corporations’ cash level is up, but so is their level of debt – incidentally, what is often touted is the former, not the latter. So it can be argued that, aware of all this, corporate management does not view the current environment as deserving aggressive investments.

Interest rates have been artificially suppressed for too long, hence the artificial nature of end-demand. The root of the problem lies in debt, and not much progress has been made on that front. At the federal level, debt has doubled the last seven years. Post-Great Recession, households did begin a process of deleveraging, but leverage is growing again. Thanks to the Federal Reserve’s ultra-easy monetary policy, corporations have managed to mend their balance sheets; low interest rates have helped both balance sheet (debt refinancing) and income statement (low interest payments). Corporations’ cash level is up, but so is their level of debt – incidentally, what is often touted is the former, not the latter. So it can be argued that, aware of all this, corporate management does not view the current environment as deserving aggressive investments.

If business is hesitant, and consumers aggressive, then a natural question arises about the sustainability of this trend. As the middle chart shows, consumers have benefited greatly from Fed-engineered low interest rates. There has been a sharp drop in the household financial obligations ratio (which encompasses payments on outstanding mortgage and consumer debt, auto lease payments, rental payments on tenant-occupied property, homeowners’ insurance, and property tax payments, and is calculated as a ratio of debt payments to disposable personal income). Lower debt payments have probably encouraged them to once again begin to take on more debt. Liabilities of households and non-profit organizations peaked at $14.6tn in 3Q08 – for reference, 10 years prior to that, this number stood at $6.1tn – bottomed at $13.5tn in 3Q12 and is inching back up again, at $13.8tn by 4Q13. There is progress on the home mortgage front – from $10.7tn in 1Q08 to $9.4tn in 4Q13 – but at $3.1tn consumer credit is at all-time highs. The point is, the current trend is unsustainable given trends in employment and what is occurring in the labor force.

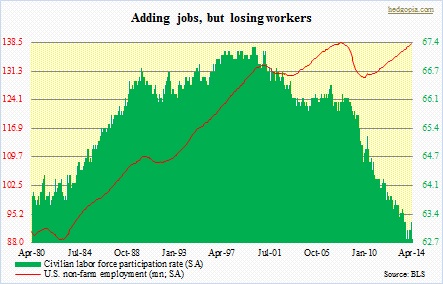

After $3.5tn of monetary stimulus from the Fed the last five years – we are not even counting the stimulus that was poured fiscally – non-farm employment is now back at the pre-recession level. Even more worrisome is the drop in the civilian labor force participation rate. Not to mention the fact that real hourly earnings have barely budged in the current cycle. The lesson in all this is probably this: when you have a structural problem, monetary policy alone does not/cannot act as a panacea. Yes, asset prices have reacted favorably to the Fed’s generous monetary handouts. Yes, there probably is some wealth effect. But for consumers to continue to do the heavy-lifting, wages need to rise and jobs need to be plentiful. And this would not occur unless corporations seriously believe in the health of the consumer. A Catch-22, but from corporations’ perspective, it is practicality, especially considering interest rates are at historic lows and the only major next move – whenever that is – is up from here.

After $3.5tn of monetary stimulus from the Fed the last five years – we are not even counting the stimulus that was poured fiscally – non-farm employment is now back at the pre-recession level. Even more worrisome is the drop in the civilian labor force participation rate. Not to mention the fact that real hourly earnings have barely budged in the current cycle. The lesson in all this is probably this: when you have a structural problem, monetary policy alone does not/cannot act as a panacea. Yes, asset prices have reacted favorably to the Fed’s generous monetary handouts. Yes, there probably is some wealth effect. But for consumers to continue to do the heavy-lifting, wages need to rise and jobs need to be plentiful. And this would not occur unless corporations seriously believe in the health of the consumer. A Catch-22, but from corporations’ perspective, it is practicality, especially considering interest rates are at historic lows and the only major next move – whenever that is – is up from here.

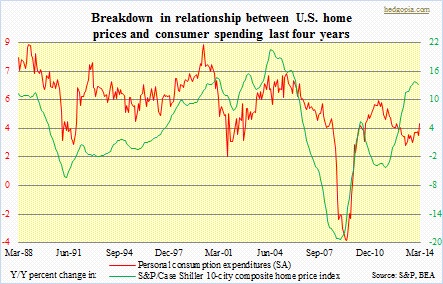

Low interest rates have also lit a small fire underneath home sales. Home prices have rebounded. Mortgage rates are higher from the lows of one year ago, yet historically they are still very low. Yet, recent data suggests wind may be coming out of housing sails. For the average consumer, home prices perhaps matter more than stock prices. In the accompanying chart, the correlation between personal consumption expenditures and the S&P/Case Shiller 10-city composite home price index is 0.86, though there has been some breakdown in this relationship in recent years. Since November last year, y/y increase in the index has been ticking down.

Low interest rates have also lit a small fire underneath home sales. Home prices have rebounded. Mortgage rates are higher from the lows of one year ago, yet historically they are still very low. Yet, recent data suggests wind may be coming out of housing sails. For the average consumer, home prices perhaps matter more than stock prices. In the accompanying chart, the correlation between personal consumption expenditures and the S&P/Case Shiller 10-city composite home price index is 0.86, though there has been some breakdown in this relationship in recent years. Since November last year, y/y increase in the index has been ticking down.

Equities in general continue to be top-heavy, and are struggling to gain traction. Breadth is narrowing, and former mo-mo favorites have been unable to seriously attract new money. There are some signs of distribution. I initiated short positions on some ETFs this AM.