The phrase quantitative easing elicits diverse reaction.

For some, QE was what saved the U.S. economy post 2007/2008 crisis and boosted both housing and stocks. For others, all it did was create this huge asset inflation, and further widen the gulf between the haves and haves-not. The truth probably lies somewhere in between. If not for the aggressive Fed action in the latter months of 2008 and early 2009, the U.S. economy was probably headed for a much deeper contraction than what we actually witnessed. But did the economy need continued Fed support/hand-holding in 2010 and 2012 – particularly the latter? Probably not. Hindsight is always 20-20, but all that monetary stimulus did was essentially bring the economy back to pre-crisis days. The recovery has been anemic, and corporations do not seem interested in aggressively investing in both capital and labor. The sustainability aspect of the recovery is in question.

For some, QE was what saved the U.S. economy post 2007/2008 crisis and boosted both housing and stocks. For others, all it did was create this huge asset inflation, and further widen the gulf between the haves and haves-not. The truth probably lies somewhere in between. If not for the aggressive Fed action in the latter months of 2008 and early 2009, the U.S. economy was probably headed for a much deeper contraction than what we actually witnessed. But did the economy need continued Fed support/hand-holding in 2010 and 2012 – particularly the latter? Probably not. Hindsight is always 20-20, but all that monetary stimulus did was essentially bring the economy back to pre-crisis days. The recovery has been anemic, and corporations do not seem interested in aggressively investing in both capital and labor. The sustainability aspect of the recovery is in question.

Of course, it can be argued that if not for the Fed action the economy would, for instance, still be down millions of jobs from pre-crisis level. But at the end of the day, one has to ask, benefit at what cost? By not letting the economy follow its own natural course, the Fed is essentially trying to micro-manage the business cycle – sort of in an attempt to deny contraction from ever taking place! A noble goal, but in a $17-trillion economy, how practical is that?

If things unfolded as per Fed’s intentions, then we would have had much healthier bank-loan creation, much stronger growth in jobs, higher inflation, much stronger corporate capex, and what not. Rather, artificial support for too long denies the process of creative destruction and tends to sustain zombie companies.

If things unfolded as per Fed’s intentions, then we would have had much healthier bank-loan creation, much stronger growth in jobs, higher inflation, much stronger corporate capex, and what not. Rather, artificial support for too long denies the process of creative destruction and tends to sustain zombie companies.

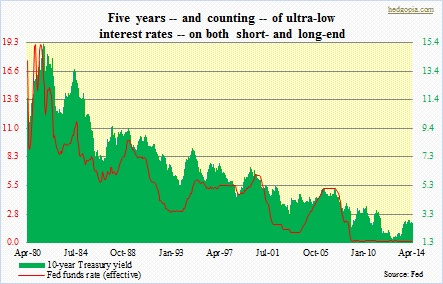

Accordingly, investors’ risk appetites have risen, which almost always eventually ends up in tears. Credit spreads are razor-thin. And perhaps the worst of all, the $3.5tn the Fed has created since crisis days has enabled Washington D.C. to continue to spend beyond what it takes in. And then there is a whole set of investor class who suffer simply because rates have stayed too low for too long.

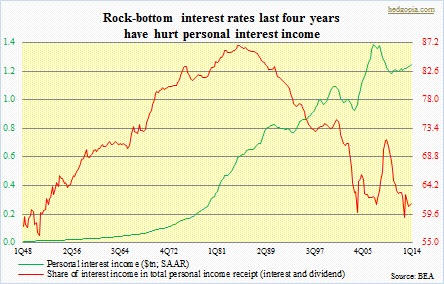

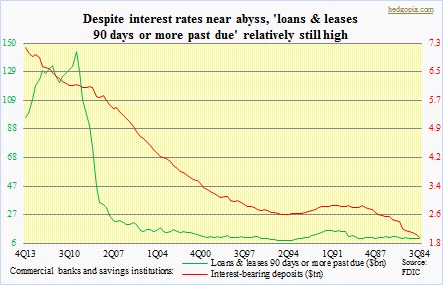

Low interest rates are meant to stimulate economic activity. The current cycle is no exception. But there is a price to pay. The chart above shows how personal interest income peaked at $1.38tn in 3Q07 (SAAR), and as of 1Q14 was still about $140bn short of that high. Most economic indicators are either at or past 2007/2008 level, but not interest income. The irony is, at $7.2tn as of 4Q13, interest-bearing deposits at U.S. commercial banks and savings institutions were at all-time highs. Here is another irony. Despite the current low rate environment, ‘loans & leases 90 days or more past due’ is off 1Q10 high, but substantially above 2007 levels. The ten-year treasury in that year yielded between four and five percent, versus well under three percent now.

Low interest rates are meant to stimulate economic activity. The current cycle is no exception. But there is a price to pay. The chart above shows how personal interest income peaked at $1.38tn in 3Q07 (SAAR), and as of 1Q14 was still about $140bn short of that high. Most economic indicators are either at or past 2007/2008 level, but not interest income. The irony is, at $7.2tn as of 4Q13, interest-bearing deposits at U.S. commercial banks and savings institutions were at all-time highs. Here is another irony. Despite the current low rate environment, ‘loans & leases 90 days or more past due’ is off 1Q10 high, but substantially above 2007 levels. The ten-year treasury in that year yielded between four and five percent, versus well under three percent now.

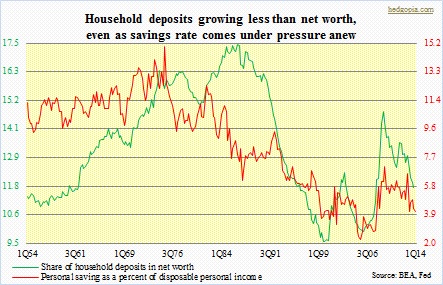

Low interest rates not only hurt household income but also deposits, as some of that income gets socked away in the form of deposits. The accompanying chart reveals how growth in deposits has lagged growth in net worth the past five years. This hurts saving, as households are re-leveraging. Hypothetically, if personal interest income in 2013 equaled 2007’s and all of that was saved, that would have lifted the savings rate to 5.6 percent from the actual 4.5 percent. Of course, this is a big hypothesis, as this economy is not strong enough to deal with a ten-year in the four- to five-percent range. From this perspective, QE is robbing savers to save spenders.

Low interest rates not only hurt household income but also deposits, as some of that income gets socked away in the form of deposits. The accompanying chart reveals how growth in deposits has lagged growth in net worth the past five years. This hurts saving, as households are re-leveraging. Hypothetically, if personal interest income in 2013 equaled 2007’s and all of that was saved, that would have lifted the savings rate to 5.6 percent from the actual 4.5 percent. Of course, this is a big hypothesis, as this economy is not strong enough to deal with a ten-year in the four- to five-percent range. From this perspective, QE is robbing savers to save spenders.