Within a year, US interest rates have gone up a lot, with the fed funds rate having risen from zero-bound to north of 4.5 percent currently. In the futures market, traders expect the benchmark rates to peak between 550 basis points and 575 basis points by July. This will have further pushed up rates on credit cards, among others. Consumers are heavily relying on these loans. In the quarters to come, delinquency rate on consumer loans can only go up.

Last March, the fed funds rate remained languished in a range of zero to 25 basis points, having sat there for two long years (Chart 1). The Federal Reserve has now pushed up these benchmark rates between 450 basis points and 475 basis points.

Other rates have followed suit.

The 10-year treasury yield tagged 1.68 percent last March and then rose all the way to 4.33 percent by October – currently yielding 3.93 percent. As long rates moved higher, they impacted several other rates, including the 30-year fixed mortgage rate which is currently at 7.1 percent.

The fed funds rate is not done going up. In the futures market, traders believe the fed funds rate will have ended 2024 between 400 basis points and 425 basis points, but before that it is expected to continue to rise until it reaches 550 basis points and 575 basis points by this July.

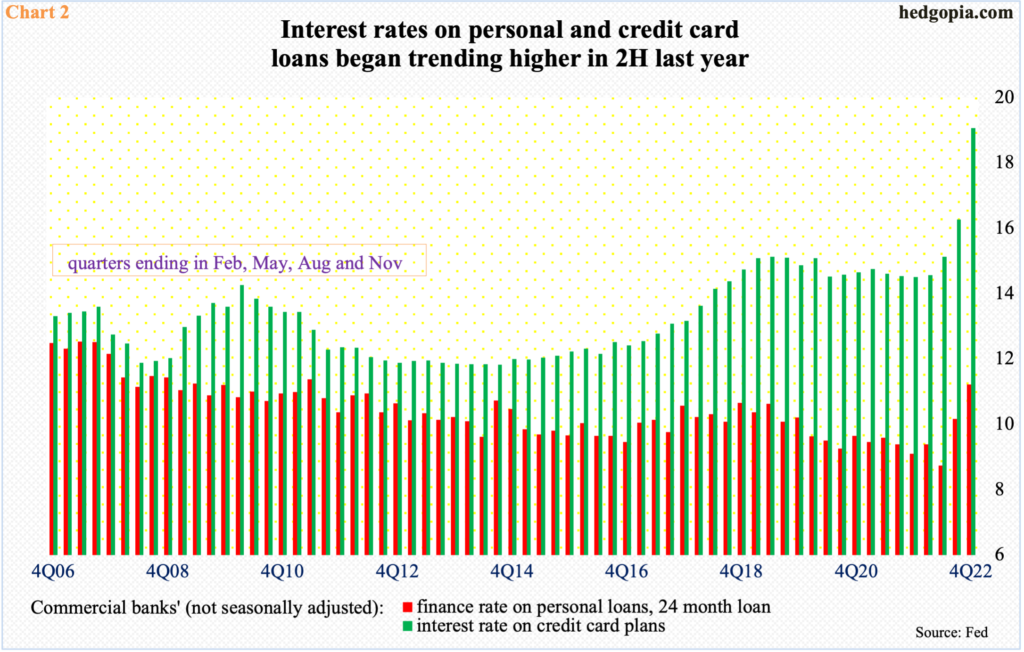

The fed funds rate serves as the basis for the prime rate, which is often used as a benchmark for a whole host of loans including credit cards. The prime rate, which currently stands at 7.75 percent, up from 3.25 percent last March, still has upward bias. As do interest rates on personal and credit card loans, for instance.

Commercial banks’ interest rate on credit card plans ended 2022 at 19.1 percent; similarly, the finance rate on personal loans at commercial banks was 11.2 percent. They both decisively rose in the second half last year (Chart 2) and in all probability are headed higher in quarters to come before they take a break.

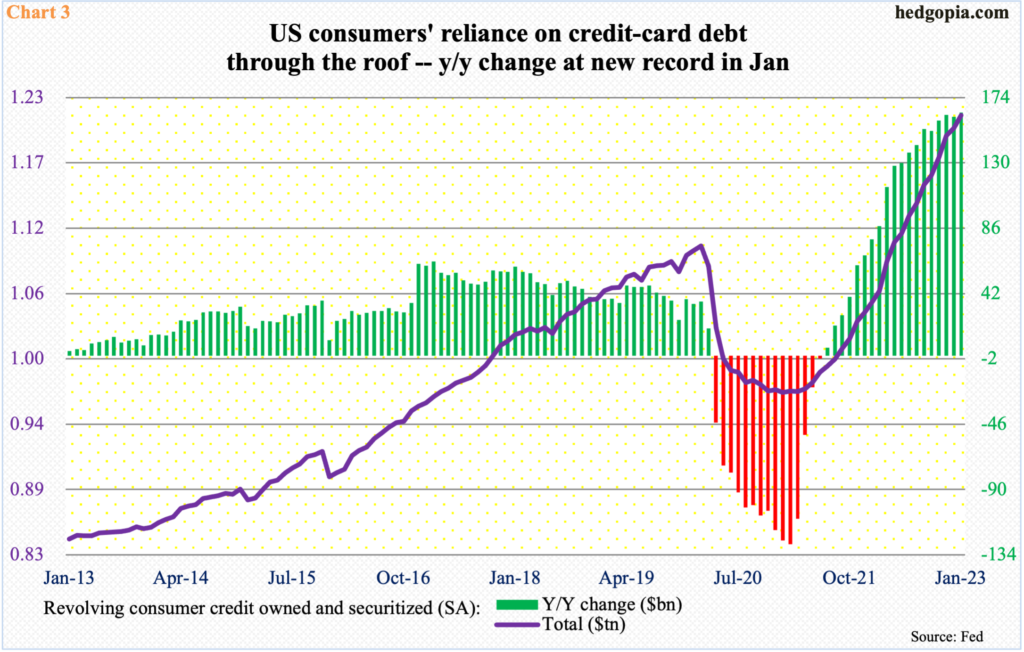

US consumers have been the bright spot in the economy, but at the same time their fascination with credit knows no bounds. Their balance sheet improved greatly owing to Covid stimulus, but these savings are being run off. This is taking place at a time when interest rates have risen substantially in the past year and reliance on leverage has gone up.

In January, revolving consumer credit, which is a committed loan facility allowing a borrower to borrow up to a limit – essentially credit cards – increased $11.2 billion month-over-month to $1.21 trillion – a new record. For six consecutive months through January, these loans were each up north of $150 billion year-over-year, with January adding $164 billion, which was a new record (Chart 3).

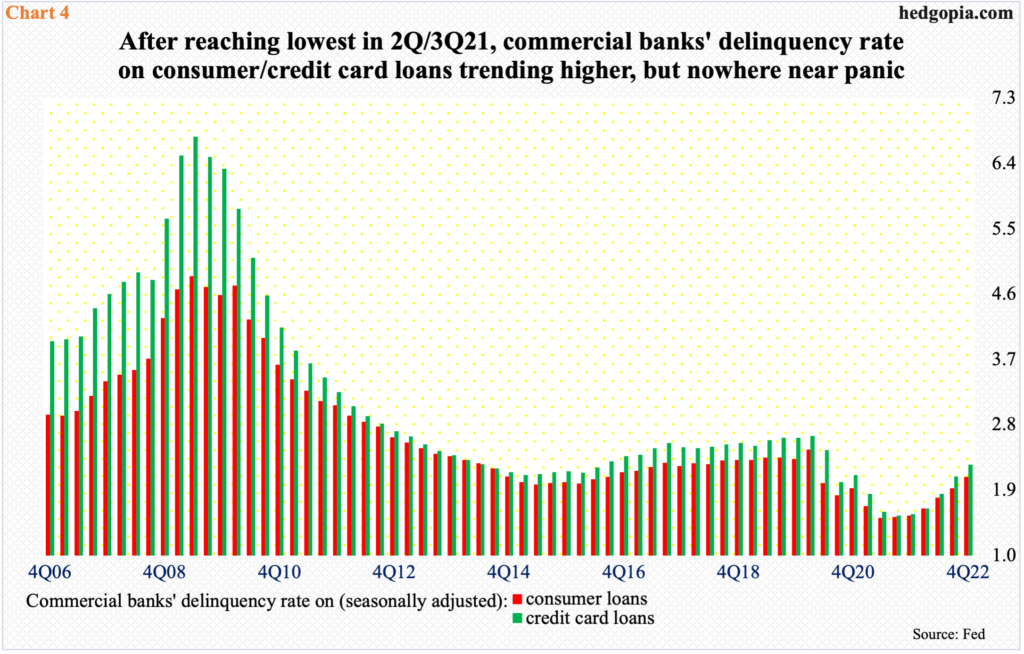

Thus far, delinquency is not a problem, but odds favor it is lurking out there. Delinquent loans are those past due 30 days or more and still accruing interest plus those in non-accrual status.

In 4Q22, the delinquency rate on consumer and credit card loans respectively stood at 2.1 percent and 2.3 percent. Historically, these remain very low (Chart 4). Nevertheless, they are trending higher after hitting the lowest in 2Q/3Q of 2021.

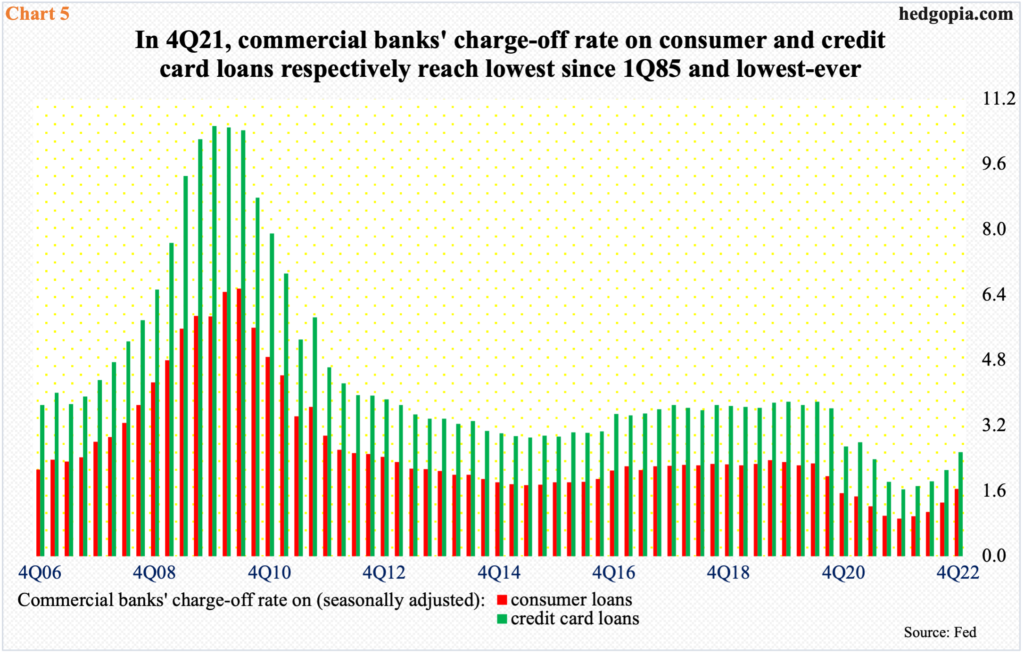

This will have implications for commercial banks’ charge-off rates. Charge-offs are the value of loans removed from the books and charged against loss reserves. The charge-off rate shows the percentage of balances in default relative to the outstanding amount.

In 4Q22, the charge-off rate on consumer and credit card loans were 1.7 percent and 2.6 percent respectively. Once again, historically, these rates remain very manageable, but it is the trend that counts. They both bottomed in 4Q21 – at 0.9 percent and 1.6 percent, in that order.

The trend is up. It is just a matter of how high they will go before going the other way. Given the Fed’s commitment to continued tightening, suffice to say that the charge-off rate is headed higher. Time will tell how high. The 2009-2010 bars are helpful to get a perspective, but things will have to evolve pretty bad for charge-offs to charge toward those highs.

Thanks for reading!