- U.S. corporate share buybacks in full swing; debt issuance on track for yet another record year

- Despite surge in issuance and rising share of high-yield debt, there is silver lining in cloud

- Corporations have been extending maturity as well as increasingly using fixed rates

U.S. corporations get the flak for not investing enough in capital projects and at the same time aggressively pursuing share buybacks.

Capital expenditures of non-financial corporations declined to as low as $937.2 billion in 3Q09 (at a seasonally adjusted annual rate), rising to $1.77 trillion by 4Q14. This is nothing to sneeze at, but considering that the economy is six years into expansion and corporate profits are near all-time highs, capX remains relatively subdued.

Corporate buybacks on the other hand have gone from a low of $149.5 billion in 2009 to $679.5 billion in 2014 (courtesy of Birinyi Associates). Year-to-April, large corporations have authorized $398 billion in buybacks, $141 billion in April alone. At this pace, 2015 will be a record year (2007 was $761.8 billion).

These are humongous numbers. Not surprisingly, corporations have also been aggressively issuing bonds.

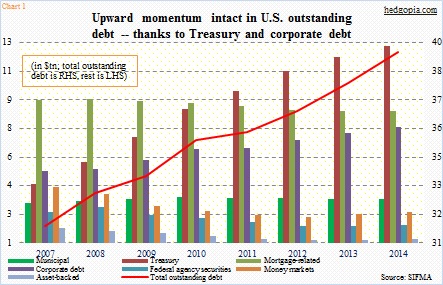

Chart 1 plots U.S. outstanding debt along seven different categories. Of those, municipal, Treasury, and corporate debt were higher in 2014 compared to 2007. Treasury debt has gone through the roof – from $4.5 trillion to $12.5 trillion. Comparatively, the rise in corporate debt has been muted, nevertheless rose from $5.2 trillion to $7.8 trillion.

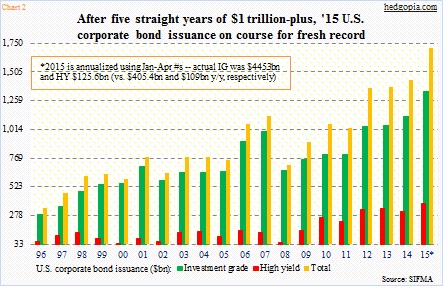

From 2010 to 2014, corporate debt issuance has been north of one trillion dollars, with each of the last three years a record. Year-to-April, corporations have issued $570.9 billion. At this pace, 2015 will be another record year – on track for north of $1.7 trillion.

High-yield’s share in total issuance is ominously noteworthy. Investment-grade was 78.3 percent in 2014, down from 93.9 percent in 2008. High-yield issuance was north of $300 billion in 2012-2014, with 2015 on track for a record year (Chart 2). In this yield-hungry environment, high-yield remains in demand. This has potential to cause problems in the future, timing notwithstanding.

With that said, here is a silver lining in this rather cloudy state of affairs.

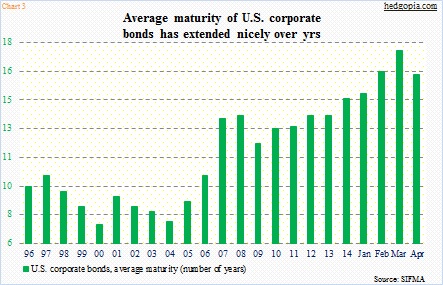

Corporations are extending their debt maturity.

The average maturity of corporate bonds has steadily gone up. The SIFMA data goes back to 1996. Barring a spike in 2007-08, maturity has steadily risen from 2004. It was 14.7 years last year, and rose further this year, with March at 17.5 years (Chart 3).

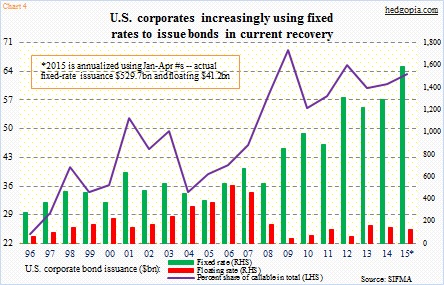

They are also increasingly using fixed rates to issue bonds. In Chart 4, the green bars represent the amount issued with fixed rates, versus the red ones with floating rates. The former rose from $539.1 billion in 2008 to $1.3 trillion last year, even as the latter went from $169.1 billion to $142.2 billion. In a low-rate environment, this is what is expected of corporate treasurers to do, and they have not disappointed. In terms of debt-servicing, this will go a long way.

While the mix between fixed and floating rates makes perfect sense, the mix between callable and non-callable probably less so. By the way, the total issuance in Chart 1 only includes non-convertible debt. Convertible debt makes up a tiny portion of the total. In 2014, it was $37.5 billion, so the total including non-convertible would be $1.47 trillion, instead of $1.43 trillion in the chart.

The violet line in Chart 4 is the share of callable debt in the total, and it has been rising. Makes you wonder why. Issuers have the option to redeem callable bonds prior to maturity. Often, owners are paid a premium to let go of their bonds. For the most part, a bond is redeemed if interest rates have declined since issuance. Rates are already low historically. How low are they going to go? Are these treasurers sending some kind of a signal? That in due course rates are headed lower still before they head higher?

Other than that, they have done a good job in extending the maturity and increasingly relying on fixed rates even though the debt pile itself is growing for the wrong reasons – financial engineering, that is.

Thanks for reading!