- Divergence between jobs momentum and other macro data points

- Annual growth in productivity past four years mere 0.68 percent

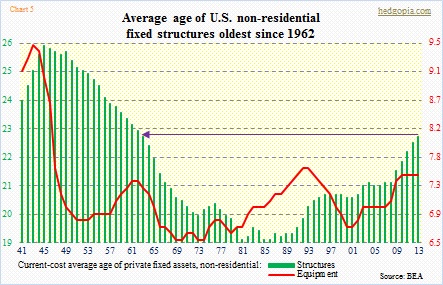

- Infrastructure, both structures and equipment, is rapidly aging

It has been more or less an enigma. The divergence between various U.S. macro data points is getting wider.

The monthly jobs number increasingly is beginning to paint a rosier picture, but several other data points are not conforming.

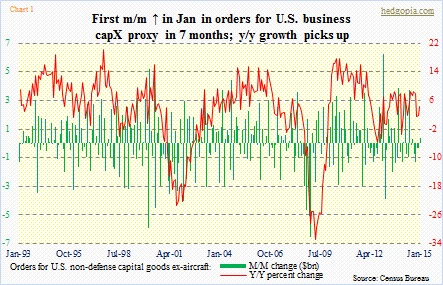

Orders for non-defense capital goods ex-aircraft, a proxy for business capital expenditures, have more or less been flattish since March last year. January saw a 4.3-percent year-over-year pop (to $70.7bn), but that was mainly due to the base effect (Chart 1). January last year was weak. Growth in February, too, should look good as the year-ago number was $67.8bn. But beginning March, y/y growth should begin to look weak as last March orders jumped to $71bn, which since has stayed in that range or higher.

But one does not get that feeling looking at non-farm payroll.

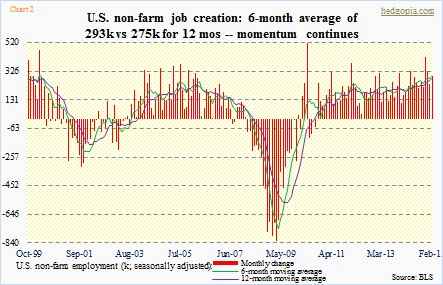

The past four years (going back to February 2011), growth in non-farm payroll has averaged 210k per month, higher than the 150k average in the recovery-to-February. This compares with a monthly average of 99k during the December 2001-November 2007 expansion and 203k during the April 1991-February 2001 boom. So versus the 1990s expansion the current average falls short. But here is the thing. Momentum has been building in recent months. The past 12 months, it has averaged 275k. The past six months, it is even higher – 293k. Since December 2013, the six-month average has exceeded the 12-month average (Chart 2).

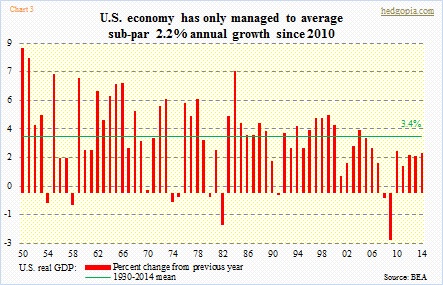

The GDP, on the other hand, lacks the same momentum. Annual growth is beyond sub-par. Since 1930, real GDP has averaged 3.4 percent (Chart 3). Since 2010, however, it has only managed an annual 2.2 percent. 2014 was 2.4 percent, only slightly up from 2.2 percent in 2013. The last time the economy grew faster than the long-term average was in 2004. And listen to this! As of March 6 (with three weeks remaining for the quarter), the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model is forecasting a rather shocking 1.2 percent real GDP growth for the current quarter.

So just what is going on?

At least part of the answer probably lies in what is going on in productivity, which has been tanking.

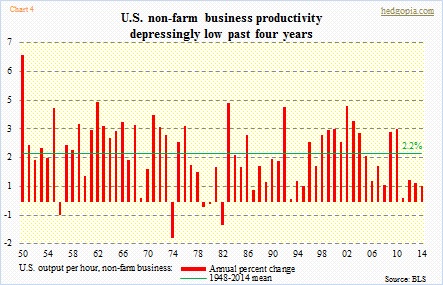

Going all the way back to 1948, annual growth in non-farm productivity has averaged 2.2 percent (Chart 4). Since 2005, there have only been two years – 2009 and 2010 – in which productivity has exceeded the long-term average. The remaining eight years were all below, some of them substantially. The past four years, output per hour has only risen at an average of 0.68 percent! Contrast this with the 1995-2004 period that had only two years of below-average productivity – 1995 and 1997.

The U.S. economy has lost its productivity mojo.

Yes, too many low-paying jobs have been created in the current recovery, increasingly looking like it is taking more people to produce the same amount of output. Stagnant to dropping productivity also partly explains stagnant wages.

But deep down, the reason for productivity slump had been building. The nation has not been investing. Plain and simple. Look at the way infrastructure is aging (Chart 5). The average age of private fixed structures (both residential and non-residential) has risen from 23.9 in 2007 to 26.3 in 2013, equipment from 6.9 to 7.4. On the non-residential side (which is what Chart 5 portrays), the average age of structures is the highest since 1962, even as equipment, which has gone sideways since 2010, is the highest since 1993. In the current recovery, the age of non-residential structures has gone up from 21 in 2007 to 22.5 in 2013, and equipment from seven to 7.5. Digging deeper, the age of hospital (20 years in 2013) is the highest since 1949, warehouses (21 years) highest since 1971, air transportation (22.4 years) highest since 1925, among others.

Perhaps the rhetorical headline question should instead be: Is the recent momentum in jobs giving us a false sense of security?