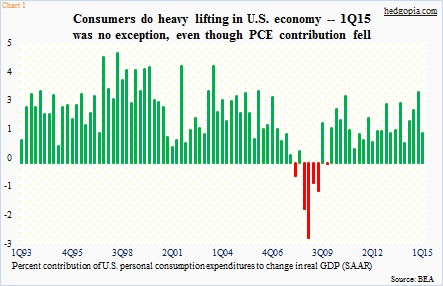

- U.S. consumer spending, accounting for >2/3rds of economy, key to growth

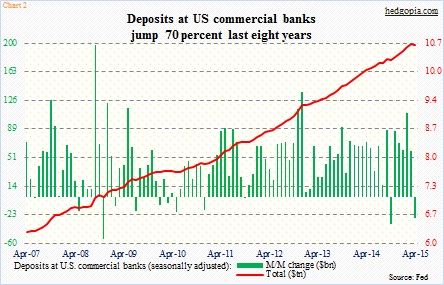

- Over last eight years, bank deposits have grown 80 percent

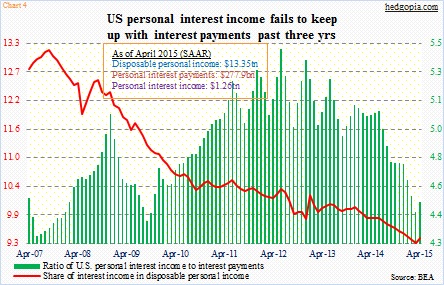

- But interest income suppressed due to ZIRP

Do consumers always benefit from low interest rates? At first glance, that seems like a logical conclusion, but a deeper look reveals there is more to it than meets the eye.

April’s lackluster consumer spending has the second quarter stumbling out of the gate. In the U.S. economy, consumers do the heavy lifting. Last year, personal consumption expenditures (PCE) accounted for 68 percent of real GDP. It is rare for the component to subtract from the GDP. In fact, during the 2001 dot-com recession, PCE was always a positive contributor; not so in the Great Recession, though (Chart 1). In 1Q15, PCE’s contribution was 1.23 percent, which was down substantially from 2.98 percent sequentially. Nonetheless just imagine how 1Q would look like if consumers did not step up to the plate. Real GDP contracted 0.7 percent in the quarter.

So it makes sense why flattish consumer spending in April is making those hoping for a snapback in 2Q output uncomfortable. Particularly so when incomes are rising. Not that incomes are going gangbusters, but they are rising. April personal income rose 4.1 percent year-over-year. Nominal average hourly earnings have been rising in a two-plus percent rate annually. Sluggish yes, but keeping up with/slightly better than inflation.

In the meantime, over the past eight years, deposits at U.S. commercial banks have gone up 70 percent, to $10.7 trillion (as of April). Post-Great Recession, the economy has grown sub-par. This is no news. Real GDP has averaged 2.2 percent, versus 3.3 percent since 1947. At the same time, the red line in Chart 2 has been on a from-lower-left-to-upper-right journey. Therein lies the rub. Probably.

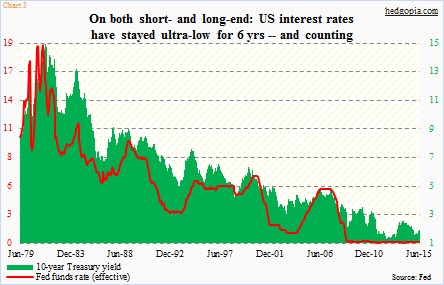

Interest rates are at historical lows – both short- and long-term. Short rates have been near zero for over six years now (Chart 3). It has been a great time to be a debtor. U.S. auto sales are on track for 17-million-plus this year. By 1Q15, auto loans were just under $1 trillion; student loans have surged to $1.36 trillion. Based on the first four months, corporate debt issuance is on track for $1.7 trillion this year – sixth consecutive trillion-plus year. Life is good.

Well. That will depend on who is looking at it. Interest rate giveth and interest rate taketh away. Chart 4 plots a ratio of personal interest income to interest payments. And it has been under consistent pressure; it did nudge up in April, though. It is the same picture when we look at the share of interest income in disposable personal income.

This is because (1) interest income has been adversely impacted by the zero interest-rate policy, and (2) interest payments have gone up due to increasing leverage. Despite all the talk we hear about deleveraging, consumer credit has risen from $2.6 trillion when the Great Recession ended to $3.4 trillion now.

So to answer the rhetorical question in the opening paragraph, no, consumers do not all benefit from low interest rates. Given the growth in deposits, they would have fared much better if rates were higher. As would consumer spending – probably.

Thanks for reading!