- Dollar has benefited from growth/interest rate differential among countries

- Recent spurt of weak U.S. data has pushed back rate-hike expectations to late 15

- Dollar index retreats after approaching crucial Fib retracement; other levels to watch

In 2014, the U.S. economy created 3.1 million non-farm jobs, up from 2.4 million in 2013 and 2.3 million in 2012. Momentum was building. The GDP shrank in 1Q14, but snapped back in the remaining three quarters, particularly 2Q and 3Q – up 4.6 percent and five percent respectively. By August, the ISM manufacturing index stood at 58.1, highest since April 2011, and new orders index at 63.9, an eight-month high.

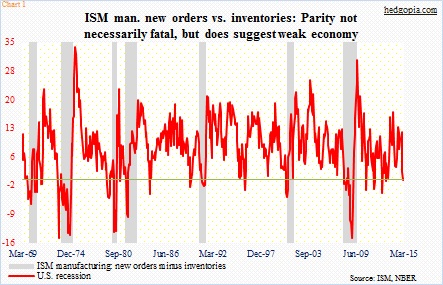

Then things began to come apart. By March, ISM new orders had dropped to 51.8 – a 22-month low; they were almost at parity with inventories, followed by parity in February (Chart 1). The Atlanta Fed is now forecasting 0.1-percent real GDP growth in 1Q.

What happened?

In an economy of this size, it is never any one particular factor. But one likely culprit is the surge in the greenback.

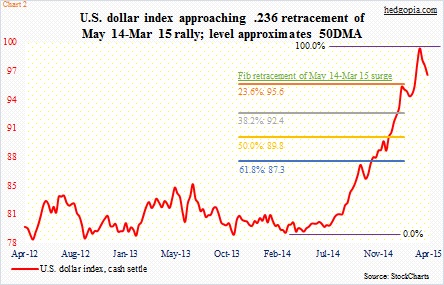

From trough to peak between May last year and March this year, the U.S. dollar index surged nearly 28 percent (Chart 2). That is in 10 months!

ISM’s manufacturing new export orders index dropped to 47.5 in March from 57 a year ago. Exports of goods and services dropped from $198.7 billion in October last year to $186.2 billion in February.

The dollar rose because both eurozone and Japanese economies were faring worse than the U.S. The Fed was winding down its QE, even as the BoJ was raising its to a whole new level and the ECB was about to begin its. Interest-rate differential was in favor of the dollar, and this was only expected to widen as the Fed was widely expected to begin to hike rates in the middle of this year.

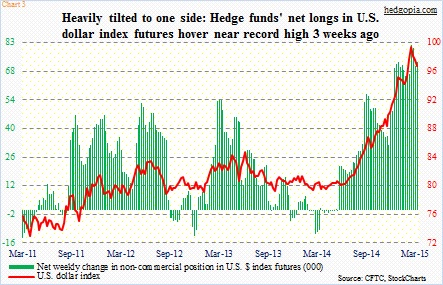

Nowhere is this rather “no-brainer” trade evident than in the futures market (Chart 3). Three weeks ago, large speculators had accumulated the largest net longs position in the U.S. dollar index – 81.3k contracts (73.1k in the most reporting period). These traders have done an excellent job of riding the dollar uptrend since the middle of last year. But this is also a group that can/often tends to miss inflection points.

Are we at/approaching one?

Market expectations for when the Fed might move have shifted, albeit slightly. The barrage of weak U.S. economic data in recent weeks/months has pushed up rate-hike expectations to later this year.

In contrast, a lower euro has helped the eurozone economy, which in 1Q may very well have outperformed its U.S. counterpart.

Against this backdrop, it is entirely possible/probable the Fed has missed a window of opportunity to hike rates. Though this is not a consensus call, just yet.

As crowded as the long dollar trade has been the past nine months, if and when sentiment changes, there are bound to be repercussions across asset classes – from large-cap U.S. stocks to exports to inflation to global commodities to emerging markets/economies.

Since its mid-March high, the U.S. dollar index has come under pressure a tad. But is this the beginning of a trend change or just a pause that refreshes itself?

For possible answers, technical analysis can help, especially because T/A is widely used in forex, and can give us guideposts to focus on.

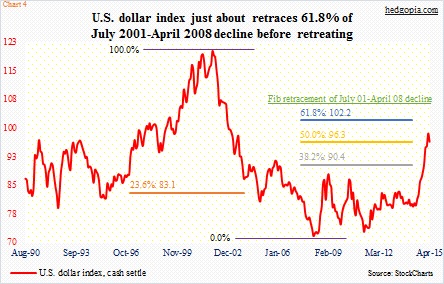

Chart 4 highlights various Fibonacci retracement levels of the July 2001-April 2008 decline. The dollar rally paused/stopped right underneath the .618 retracement. In the chart, closing price has been used. March closed at 98.66; using intra-day, price rose as high as 100.71 on the 16th. The intra-day high is not that far away from the .618 Fib retracement.

Using the same technique, we can come up with various price levels that are likely to provide support going forward. The index is fast approaching the .236 retracement of the rally since May last year (Chart 2). Dollar bulls can be expected to defend this level. They have to. This is also where the 50-day moving average lies.

IF bulls are unable to save this, then we know winds of sentiment change are beginning to blow. When that happens, the next thing to watch will be the reaction of large specs (Chart 3). There is plenty of room for those tall green bars to get smaller. In this scenario, the answer to the rhetorical question posed in the title would be, yes, the dollar can indeed become a victim of its own success.