The Fed Wednesday held interest rates steady. No surprise there. But the bank was even more dovish than markets expected. That was a surprise. Even more surprising is how stocks reacted.

The Fed Wednesday left the fed funds rate unchanged at 225 to 250 basis points. Markets expected this. Prior to the meeting, no-hike odds were 99 percent in the futures market. But the bank managed to throw markets a curve ball by tilting even more dovish than was expected.

It now expects no hike this year – quite a surprise development given nine full months remain in the year. Last December, when the Fed raised the last time, the FOMC dot plot expected two rate increases this year. That hike was a ninth 25-basis-point increase since the Fed began raising rates in December 2015 after leaving them zero-bound for seven long years.

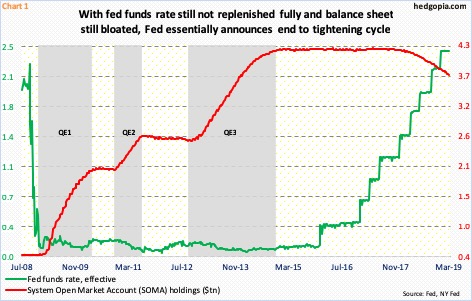

Concurrently, the Fed plans to bring the ongoing balance-sheet wind-down to an end in September. It began to run down its balance sheet in October 2017. Currently, up to $60 billion a month can roll off its balance sheet. As of Wednesday last week, System Open Market Account (SOMA) holdings stood at $3.76 trillion, down from a peak of $4.24 trillion in April 2017. Prior to three iterations of quantitative easing (QE), these holdings were merely $500 billion (Chart 1).

Why the Fed panic? Which is what it is, come to think of it.

The bank now expects 2.1 percent growth this year, down from the 2.3 percent it forecast in December. But things are not falling apart. Borrowing a quote from Wednesday’s FOMC statement, “The committee continues to view sustained expansion of economic activity, strong labor market conditions, and inflation near the committee’s symmetric two percent objective as the most likely outcomes.”

The problem with this is that there is a difference in what the Fed is saying and what it is doing. By essentially telegraphing that the tightening cycle has peaked, it is admitting the ongoing deceleration in the US economy is much worse than it expected just a few months ago.

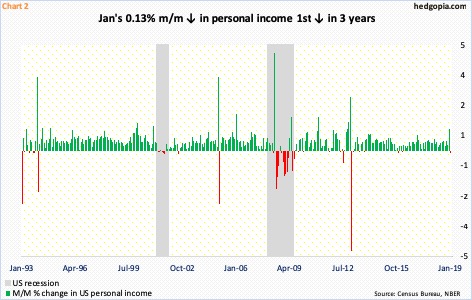

Signs of deceleration are everywhere. The jobs market has been strong. Even here, February only produced 20,000 non-farm jobs. Personal income fell 0.1 percent month-over-month in January to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of $18 trillion. This was the first m/m decline in three years (Chart 2). In 4Q18, the initial estimate showed real GDP grew 2.6 percent. Growth was 4.2 percent in 2Q and 3.4 percent in 3Q. As of March 13, the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model forecasts growth of 0.4 percent in the current quarter.

Wednesday’s FOMC decision reverberated through the markets, sending interest rates and the US dollar lower, among others. The 10-year Treasury yield fell eight basis points to 2.54 percent – now below decade-old support at 2.62 percent. The US dollar index (95.20) fell 0.6 percent to close at important support but below the 200-day moving average. Both this reaction was expected. What was unexpected was how stocks reacted.

At least in theory, an end to the tightening cycle should bode well for risk-on assets. One would think this would help stocks. Going into the FOMC decision, stocks were weak Wednesday. The S&P 500 large cap index at one time was down as much as 0.7 percent. Post-decision, it soon rallied to be up 0.4 percent, but closed down 0.3 percent.

Stocks’ unimpressive reaction probably owes to the fact that (1) they already rallied huge from late-December lows, with the S&P 500 up 20 percent, and (2) the Fed may have essentially rung an at-the-top bell. The US economy is just three months short of completing a decade of recovery/expansion. It is at the top of the cycle, not the bottom. If the economy continues to weaken, the Fed will ease – using both conventional and unconventional means (read QE). But this is not going to be a new experiment. Been there, done that.

As explained above, post-financial crisis, rates were pushed – and left – near zero for years, even as the Fed’s balance sheet ballooned. After a decade of sub-par growth, during which leverage continued to rise, the economy is begging for more monetary stimulus. What did all that stimulus achieve, and what will the new round – whenever that is? That is the question stocks will be asking this time around. The reaction function does not have to be the same as in 2008-2009.

Thanks for reading!