Having raised the fed funds rate by 525 basis points over 14 months, the Fed is under pressure to stop, but is not willing to commit to that. The culprits are sticky core inflation and financial conditions that are easing.

After Wednesday’s 25-basis-point hike in the fed funds rate to a range of 525 basis points to 550 basis points, an increasing number of market participants are now saying this is the last hike of the cycle. The Federal Reserve began its tightening campaign in March last year. Rates were zero-bound back then. They were left there for two whole years in the wake of the economic disruption caused by Covid-19.

The benchmark rates have gone up 525 basis points over 14 months. To everyone’s surprise, the economy has held up very well, as has the job market. In the futures market, traders are betting that is not going to be the case for too long. They are betting that the Fed is done raising and that the central bank would start cutting next March, reaching 400 basis points to 425 basis points by December next year (Chart 1).

Fed Chair Jerome Powell says, not so fast. In yesterday’s post-meeting press conference, he pointed out that Fed staff are no longer forecasting a recession. The FOMC statement itself upgraded economic growth from “modest” at the June meeting to “moderate”. September hence is a live meeting, with Powell saying they would be going meeting by meeting. Markets wanted to hear the word ‘terminal’ and they did not get it.

The problem is two-fold as far as the Fed is concerned. It has a dual mandate of maximum employment and price stability. The job market is on fire, with June’s unemployment rate at 3.6 percent. Growth has clearly surprised to the upside, as has unemployment. The Fed wants the job market to cool a bit so inflation gets a reprieve.

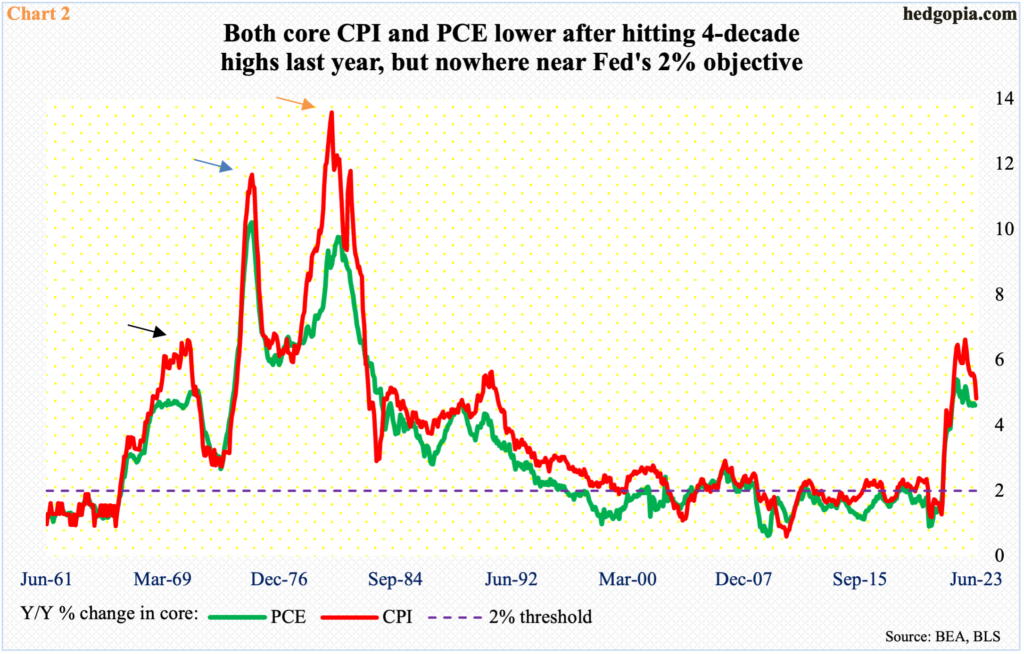

Inflation – measured primarily by the consumer price index (CPI) and the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index – has trended lower since reaching four-decade highs last year but remains way above the Fed’s two percent objective on a core basis. In the 12 months to June, core CPI grew 4.8 percent, and core PCE – the Fed’s favorite, by the way – increased 4.6 percent in the 12 months to May (June numbers are due out tomorrow). They respectively peaked last year at 6.6 percent in September and 5.4 percent in February.

Yes, the Fed will stop raising long before core PCE reaches two percent but Powell also does not expect inflation hitting two percent until 2025. Plus, there is always a risk of inflation resurgence, as was seen several times in the ’70s (Chart 2).

The bottom line is that core inflation is proving to be sticky.

The other factor consists of financial conditions which are easing. This is in stark contrast to what the Fed is trying to achieve.

The S&P 500 bottomed on October 13 last year. It had a market cap of $30.1 trillion at the end of September. Three quarters later – that is, at the end of June – this had swollen to $37.2 trillion. Moreover, July, with three sessions left, is up another 2.6 percent. That is a lot of wealth created in less than a year. This obviously impacts consumer confidence and consumption.

July’s preliminary reading showed the University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment index shot up 8.2 points month-over-month to 72.6. In June last year, confidence hit a record low 50.

This does not help a central bank that wants a slowdown in economic activity. In Wednesday’s press conference, Powell admitted that monetary policy is now restrictive, but could not say that they would like to now wait and see because (1) there are eight more weeks between now and the September meeting, and a whole host of inflation and employment reports in between, and (2) this would cause more easing in equity markets.

Thanks for reading!