Small-caps get no love. They have not for a while. Unlike its large-cap peers that keep making new highs, the Russell 2000 remains substantially below its November 2021 high. The index ceased to respond to solid jobs picture as early as 2022. Now, it is probably pricing in continued downward revision in earnings for this year and next.

Last Friday, we found out that the US economy added 272,000 non-farm jobs in May – way better than expected. This brings the monthly average this year to 248,000, versus 251,000 in all of last year.

The solid payrolls report is not matched by openings, which remain healthy but are nowhere near the levels of two years ago. Non-farm openings peaked in March of 2022 at 12.2 million. This April, they dropped 296,000 month-over-month to 8.1 million.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics only began reporting job openings in December 2000, hence lacks a long history. That said, the nearly 24 years of the series does cover three recessions – dot-com (2001), financial/housing (2007-2009) and Covid-19 (2020) – perhaps sufficient enough to show a tight relationship between openings and payrolls.

In the past, openings have tended to lead. This time around, payrolls, which set a new high of 158,543 in May, is yet to do so (Chart 1).

Small-caps act like it is just a matter of time before that happens. Small-caps by nature have much higher exposure to the domestic economy than their large-cap cousins, which also have overseas exposure. Consequently, small-caps are treated as a reliable way to take a pulse of the economy. Equity investors tend to gravitate toward these stocks when they are convinced the economy is headed for good times.

In the current cycle, however, things have not quite panned out that way. The Russell 2000 peaked in November 2021 at 2459. Back then, the Nasdaq 100 peaked in that same month, followed by the S&P 500 large cap index which did so in the following January. The latter two indices have already rallied past those highs to continuously post newer highs. The Russell 2000, in the meantime, closed last week at 2027.

In fact, the Russell 2000 refuses to respond to the ongoing strength in payrolls, losing 2100 as early as January 2022, which incidentally preceded the March 2022 peak in openings. The small cap index has struggled at that level since, with the most recent being several unsuccessful attempts the past three months (Chart 2).

Technically, 2100 also holds importance from two other angles. After the November 2021 peak, the Russell 2000 bottomed at 1641 in June 2022, which was successfully tested in October of both 2022 and 2023. A 61.8-percent Fibonacci retracement of that tumble amounts to 2144; 2100 also represents a measured-move price target post-breakout at 1900 last December. Before that, the index went back and forth between 1700 and 1900 going back to January 2022.

Last week, the Russell 2000 gave back 2.1 percent, diverging with the S&P 500 (up 1.3 percent) and the Nasdaq 100 (up 2.5 percent). The only consolation for small-cap bulls is that Friday’s intraday low of 2023 was made just above horizontal support at 2000. Concurrently, the index has also been trading within a channel since May 15th and it is currently at the lower end. This gives the bulls an opportunity to say enough is enough and rally toward 2100, but the fact remains that they will be on the defensive until that resistance is decisively taken out. Until that happens, the message small-caps are sending is that payrolls sooner or later will catch up to openings, which will not be good news for earnings, among others.

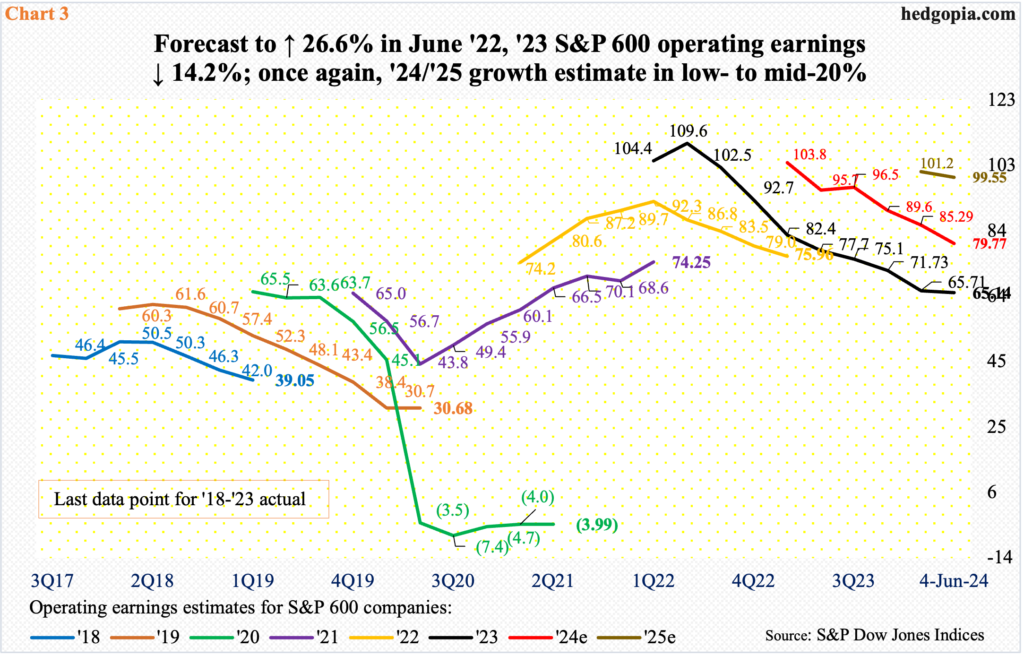

The sell-side habitually has high expectations for both this year and next.

As of last Tuesday, operating earnings estimates for S&P 600 companies stood at $79.77 for this year and $99.55 for next. Should these lofty expectations come to pass, this would mean growth of 24.8 percent next year and 22.5 percent this year. In 2023, earnings came in at $65.14, down 14.2 percent. There is the rub.

At its height in June 2022, the sell-side expected these small-cap companies to bring home $111.23 in 2023; when it was all said and done, actual earnings fell short by $46. The irony is that earnings estimates tend to show the same pattern most of the time. These analysts start out optimistic and bring out the scissors as the year progresses (Chart 3).

Even for this year, the consensus was $105.68 in March last year; for next year, estimates crested at $102.88 early last month before heading lower. If non-farm payrolls follow openings in due course – a probable case – the ongoing downward revision in earnings estimates will nothing but persist.

Thanks for reading!