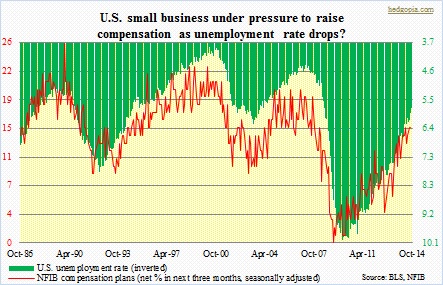

- Steep drop in unemployment rate typically would suggest upward wage pressure

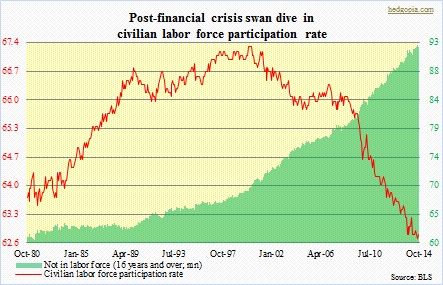

- Shrinkage in labor force takes bargaining power away from employees

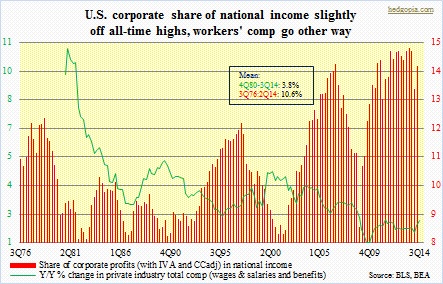

- Corporations taking increasing share of national income vs labor

It has been a while National Federation of Independent Business survey respondents have been signaling they will be coming under increasing pressure to raise employee compensation. As shown below, their comp plans closely track the U.S. unemployment rate (which in this case is inverted). The unemployment rate has dropped from a peak of 10 percent to 5.8 percent, even as the NFIB comp plans has steadily risen to 15.

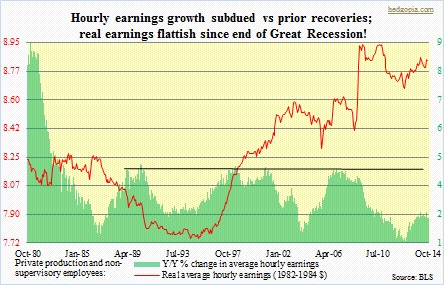

Indeed, from July 2009 to October 2014, average hourly earnings of private employees rose from $22.19 to $24.57 – for a cumulative growth of a little under 11 percent. Which looks fine until one takes inflation into account. Real hourly earnings were flat at $10.33 between the periods. (Chart below shows private production and non-supervisory employees, but the trend is the same.) With the kind of drop in unemployment rate the economy has witnessed, one would think wage pressure would be more rampant.

Most of us look at the rapidly dropping unemployment rate and contend that upward wage pressure is just round the corner. It has yet to happen. The chart below highlights the potential slack in the economy. The civilian labor force participation rate has absolutely cratered since the financial crisis – lowest since February 1978. Since July 2009, the ‘not in labor force’ category has gone up by 11mn, even as the population has grown by nearly 12mn.

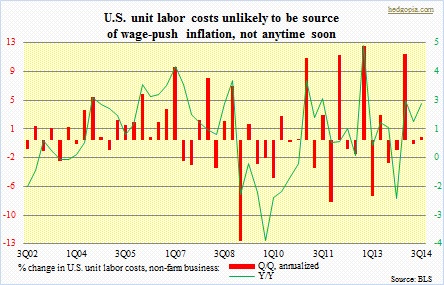

The economy grows at the rate at which the labor force is growing plus how much each worker can produce. The civilian labor force has grown by less than 2mn since July 2009. There is slack. Unit labor costs are less likely to cause wage-push inflation. They roughly equal the difference between growth in hourly comp and output per hour, rising if wages rise and falling if productivity rises. As shown below, there are spikes here and there, but the trend is flattish.

As the economy struggles to gain momentum, businesses have the luxury of wringing more efficiency from their employees. The former is not getting aggressive with capX plans, which once again translates to hesitant economic recovery and a labor force that is not yet ready to demand higher wages. From the corporate standpoint, it is a virtuous cycle, until it breaks. The chart below shows how corporations in the current recovery have been enjoying an increasing share of the national income pie, even as workers’ total comp (both wages & salaries and benefits) have been just about keeping up with inflation. Ultimately this will have adverse implications for the economy itself. Workers and consumers are one and the same.