Mediocre demand for Wednesday’s auction of $24 billion in 10-year Treasury notes probably reflects worries over rising deficit spending.

In that auction, yields obviously were not attractive enough to entice aggressive buying. Ten-year yields ended the session up eight basis points to 2.84 percent, just under Monday’s high of 2.86 percent.

In January, the 10-year broke out of a three-decade-old descending channel (Chart 1). February-to-date, yields have gone up another 12 basis points. If they hit three percent, it will be interesting to find out if that would be taken as an opportunity to go long bonds or induce further selling. The last time these yields were north of three percent was in January 2014.

The prevailing sense of fear in the bond market is palpable.

Yes, after the aforementioned breakout, the technically-oriented ones likely cut their holdings, further adding to upward pressure on yields. But it cannot just be technical.

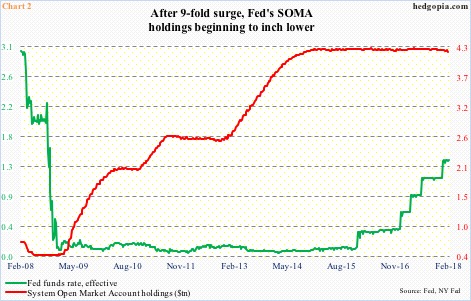

Post-financial crisis, the Fed began to both leave short rates suppressed near zero and aggressively add to its balance sheet. In September 2008, SOMA (system open market account) holdings were $473 billion. Then came three iterations of quantitative easing. By April 2017, SOMA holdings had ballooned to $4.24 trillion. As of January 31, they stood at $4.18 trillion. That is a decline of $59 billion – a chump change in the larger scheme of things.

Nonetheless, the Fed began curtailing its bloated balance sheet last October – by $10 billion/month through December, followed by acceleration in the pace every three months. By October this year, the balance sheet would have been reduced by up to $50 billion/month (comprising both Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities). We are talking $600 billion a year. At this pace, it can begin to bite.

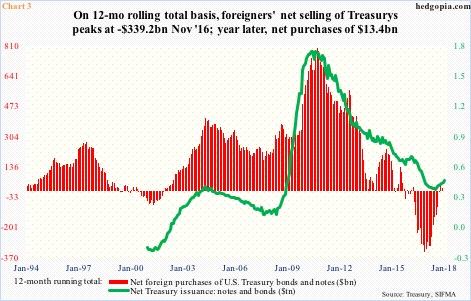

Thus far, foreigners continue to loyally purchase Treasury securities. Last November, they held $6.34 trillion in Treasury bills, notes and bonds, down slightly from October’s record $6.35 trillion.

There is this, though.

As early as March 2016, foreigners held $6.29 trillion worth, which means their holdings have essentially been flat for more than a year and a half. This is important given the green line and the red bars in Chart 3 have thus far tended to move hand in hand. Foreigners’ purchases go up as the Treasury issues more debt. The question is, will this continue? This is not just some hypothetical question. Treasury issuance is already trending higher.

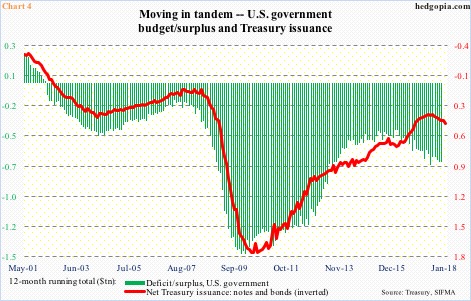

Nine years into economic recovery post-Great Recession, the U.S. still runs a deficit.

On a 12-month running total basis, the federal budget deficit totaled $684.9 billion last November. This is much better than the peak deficit of $1.48 trillion in February 2010, but has been rising since $403.6 billion in January 2016. Recent tax cuts do not help the matters.

Also on a 12-month running total basis, issuance of Treasury notes and bonds totaled $422 billion in January, and has crept higher since $335 billion last July.

This has to be nagging bond vigilantes.

As things stand, deficit spending poses the biggest risk. If there is a supply/demand mismatch for new issuance, yields will have to rise to attract bids. Simple math! Wednesday provided a window into this.

Thanks for reading!