There is probably no other price as important as the price of money – that is, interest rates. They are what grease the wheels of an economy. Simplistically, when rates are high, people are incentivized to save more. When they are low, they are motivated to do the opposite as the cost to borrow (or, rent) is less. That is how it is supposed to work. And it does exactly that most of the time anyway. In the real world, things are not always that black and white. Japan is a case in point. Interest rates in that country have been close to zero since the mid-90s, and they are yet to work wonders. Lower interest rates make it cheaper to borrow money, but they cannot in and of itself spur private demand. Japan overbuilt in the 80s, hence lacked sufficient business investment in the following years. It did not help that the yen appreciated 45 percent (against the dollar) between early-95 and mid-98. Beginning mid-07, the currency weakened 64 percent in the next four years, followed then by another cycle of strength, which probably ended up giving birth to Abenomics. Foreign exchange probably is as important a price as interest rate.

There is probably no other price as important as the price of money – that is, interest rates. They are what grease the wheels of an economy. Simplistically, when rates are high, people are incentivized to save more. When they are low, they are motivated to do the opposite as the cost to borrow (or, rent) is less. That is how it is supposed to work. And it does exactly that most of the time anyway. In the real world, things are not always that black and white. Japan is a case in point. Interest rates in that country have been close to zero since the mid-90s, and they are yet to work wonders. Lower interest rates make it cheaper to borrow money, but they cannot in and of itself spur private demand. Japan overbuilt in the 80s, hence lacked sufficient business investment in the following years. It did not help that the yen appreciated 45 percent (against the dollar) between early-95 and mid-98. Beginning mid-07, the currency weakened 64 percent in the next four years, followed then by another cycle of strength, which probably ended up giving birth to Abenomics. Foreign exchange probably is as important a price as interest rate.

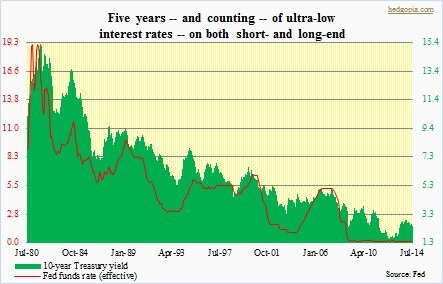

All this brings us to what the Fed is trying to achieve with its zero interest-rate policy the past five years.

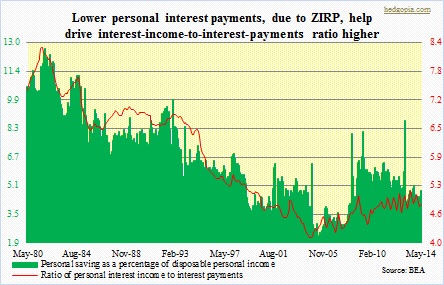

As the chart above shows, U.S. rates have been at/near historic lows for five years now. Yet since the end of Great Recession, the economy is merely muddling along – real GDP has averaged sub-two-percent growth annually, non-farm payroll just a month ago recovered all the jobs lost during that contraction, and, capacity utilization is lower than pre-Recession levels, among others. It is a different discussion altogether if what the U.S. economy is going through is comparable to the Japan experience. Nevertheless, one of the things that has been a topic of discussion in Japan and now in the U.S. is that of how low rates are negatively impacting income. Indeed, a retiree relying on interest income – bonds, bank deposits, etc. – is getting hurt. But this is just one side of the equation. Thanks to ZIRP, a homeowner, too, will have a smaller mortgage payment than what would otherwise have been. So in totality, if on one hand someone is earning less in interest income, someone else is paying less in interest payment as well. In the accompanying chart, a ratio has been calculated between personal interest income and payments, and it has been rising. Back in July 2007, Fed funds peaked at 5.26 percent, and the 10-year a month earlier at 5.1 percent; this compares with 0.09 percent and 2.48 percent last week. In September 2007, both interest payments and income (seasonally adjusted annual rates) peaked at $320bn and $1.39tn, respectively; this dropped to $257bn and $1.25tn this past May, for a decline of 20 percent and 10 percent in that order. Clearly, lower payments are helping drive the ratio higher. This is despite the fact that household credit has stayed essentially flat – $13.7tn in 3Q07 versus $13.1tn in 1Q14.

As the chart above shows, U.S. rates have been at/near historic lows for five years now. Yet since the end of Great Recession, the economy is merely muddling along – real GDP has averaged sub-two-percent growth annually, non-farm payroll just a month ago recovered all the jobs lost during that contraction, and, capacity utilization is lower than pre-Recession levels, among others. It is a different discussion altogether if what the U.S. economy is going through is comparable to the Japan experience. Nevertheless, one of the things that has been a topic of discussion in Japan and now in the U.S. is that of how low rates are negatively impacting income. Indeed, a retiree relying on interest income – bonds, bank deposits, etc. – is getting hurt. But this is just one side of the equation. Thanks to ZIRP, a homeowner, too, will have a smaller mortgage payment than what would otherwise have been. So in totality, if on one hand someone is earning less in interest income, someone else is paying less in interest payment as well. In the accompanying chart, a ratio has been calculated between personal interest income and payments, and it has been rising. Back in July 2007, Fed funds peaked at 5.26 percent, and the 10-year a month earlier at 5.1 percent; this compares with 0.09 percent and 2.48 percent last week. In September 2007, both interest payments and income (seasonally adjusted annual rates) peaked at $320bn and $1.39tn, respectively; this dropped to $257bn and $1.25tn this past May, for a decline of 20 percent and 10 percent in that order. Clearly, lower payments are helping drive the ratio higher. This is despite the fact that household credit has stayed essentially flat – $13.7tn in 3Q07 versus $13.1tn in 1Q14.

To be clear, the current Fed policy is not a panacea, as is evident in its inability to set in motion the so-called escape velocity. In fact, its policy has remained ultra-easy for so long it can be argued that it is merely setting the stage for another crisis down the line. But insofar as ZIRP-related interest dynamics are concerned, it probably helps more than harms. This has probably given the Fed reason to stay accommodative for as long as it has, notwithstanding the price to pay in the future. But, as Japan has taught us, that will be one hell of a price to pay.