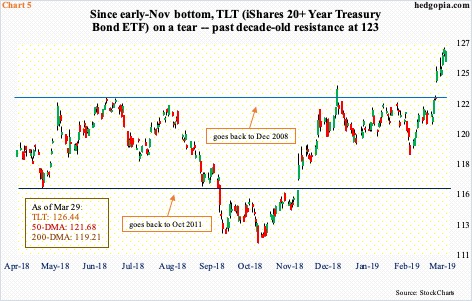

The 10-year T-yield not only lost a rising trend line from July 2016 but also decade-old support at 2.62 percent. TLT has been on a tear, but is overbought; digestion of the recent gains is the path of least resistance.

When early October last year the 10-year Treasury rate hit 3.25 percent, bond bears increasingly felt vindicated. This was the highest level since bottoming at 1.34 percent in July 2016. Along the way, in April last year the 10-year broke out of a three-decade-old descending channel.

By late September, non-commercials had built record net shorts in 10-year note futures – 756,316 contracts (Chart 1). It was becoming a crowded trade.

From that October high, rates then came under pressure for three weeks, before once again rising to 3.24 percent by Early November. Then the bottom fell. By then, non-commercials had already been actively cutting back. By early January, these notes were yielding 2.55 percent. For the first two and a half months this year, the 10-year rate (2.41 percent) remained range-bound between 2.62 percent, which goes back a decade, and 2.8 percent. Mid-March, bond bears could no longer defend 2.62 percent, followed by a quick drop to last Wednesday’s intraday low of 2.36 percent.

The loss of 2.62 percent preceded mid-December loss of a rising trend line from the July 2016 low (arrow in Chart 2). The two-year has suffered technical damage and could eventually head toward two percent. With that said, bond bears have an opportunity to stabilize matters here. The daily is way oversold. Last Thursday flashed a spinning top. Support around that session’s low goes back eight-plus years. Friday saw another spinning top. Shorter-term moving averages are still falling, so damage-repair can take time. In the best of circumstances, breakdown retest of 2.62 percent is the ideal scenario for bond bears.

The Fed lent a helping hand in loss of that crucial support. The FOMC met on March 19-20, holding interest rates steady at 225-250 basis points. This was expected, but not the dovish turn it took, which was much sharper than markets expected. The bank now expects no hike this year. Last December, when it last raised, the FOMC dot plot expected two rate increases this year. That was the ninth 25-basis-point increase since the Fed began raising rates three years ago. Concurrently, the Fed plans to end the ongoing balance-sheet wind-down in September. It began to run it down in October 2017. Currently, up to $60 billion a month can roll off. As of Wednesday, System Open Market Account (SOMA) holdings stood at $3.75 trillion, down from a peak of $4.24 trillion in April 2017. Prior to three iterations of QE, these holdings were $500 billion.

On March 20, the 10-year yield responded to this dovish message by dropping eight basis points to 2.54 percent. Policymakers’ sudden U-turn was surprising, considering that economic data had been decelerating for a while. Real GDP grew 4.2 percent in 2Q18, which then softened to 3.4 percent in 3Q and 2.2 percent in 4Q. As of last Friday, the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model was forecasting 1.7 percent growth in real GDP in 1Q19.

In February, manufacturing activity fell 2.4 points month-over-month to 54.2, which was the lowest since November 2016. Last August’s 60.8 was the highest since 61.4 in May 2004. Similarly, sales of both existing and new homes peaked as early as November 2017 at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 5.72 million units and 712,000 units, respectively (Chart 3). In fact, sales have picked up of late, with existing at 5.51 million units and new at 667,000 in February, having bottomed at 4.93 million in January and new at 552,000 last October.

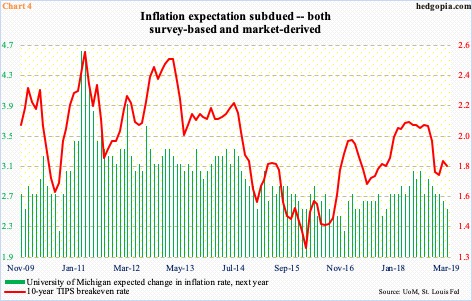

Inflation is subdued, and has been that way for a while. Both core PCE and core CPI have been trending lower since last July’s high (chart here). Core PCE, which is the Fed’s favorite measure of consumer inflation, rose at an annual rate of 1.79 percent in January. The Fed has a two percent target. Besides other softening data, this too gives the Fed leeway to go on the sidelines, not to mention subdued inflation expectations.

Chart 4 plots the University of Michigan’s inflation expectation for next year along with the difference between the 10-year yield and the 10-year TIPS (Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities) rate. The latter is the inflation breakeven rate, which essentially tells us what investors expect inflation to average over the next 10 years. It is falling. Bonds like that.

Since early November last year, bonds have rallied massively. TLT (iShares 20+ year Treasury bond ETF) went from $111.90 to last Thursday’s high of $126.69. It closed out the week at $126.44. In doing so, the ETF not only cleared seven-year resistance just north of $116 but also $122.50s (Chart 5). The latter goes back a decade. Technicians could be eyeing a measured-move target $128-$129.

After breaking out of $122.50s eight sessions ago, TLT went nearly parabolic. The daily in particular is way extended. A pause is possible.

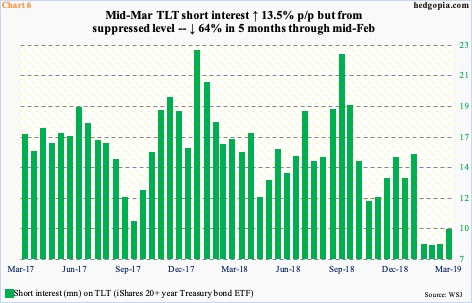

TLT shorts have already been squeezed. Mid-September last year, short interest jumped to 22.7 million shares, which in the next five months collapsed to 8.2 million (Chart 6). Mid-March, it rose 13.5 percent period-over-period to 9.4 million. Potential fuel for squeeze has pretty much dried up.

Besides technical overbought conditions, this is one more reason TLT could be in the process of peaking near term. In a scenario in which the 10-year rate heads toward two percent, TLT has more room to rally. But that may have to wait. This likely creates an opportunity for a hypothetical iron condor trade.

TLT May 17th iron condor:

- Long 130 call at $0.60

- Short 129 call at $0.80

- Short 123 put at $0.55

- Long 122 put at $0.35

It is a limited-risk, non-directional strategy – combining a bear call spread with a bull put spread. The trade earns $0.40 in credit, with $0.60 at risk. Breakeven points are $129.40 and $122.60.

Thanks for reading!