Even though Chair Powell said it is far too early to declare victory, he and his team did exactly that yesterday when they caught markets by surprise by making a hard dovish turn. The dot plot now expects up to three 25-basis-point cuts, up from two during the September meeting. Markets want more, with expectations high that the Fed will acquiesce.

The Jerome Powell-led Federal Reserve made a significant pivot Wednesday, which markets treated as a mini shock and awe of sorts. As expected, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) stood pat, leaving the fed funds rate unchanged at a range of 525 basis points to 550 basis points. In March last year when the tightening cycle began, the benchmark rates were between zero and 25 basis points.

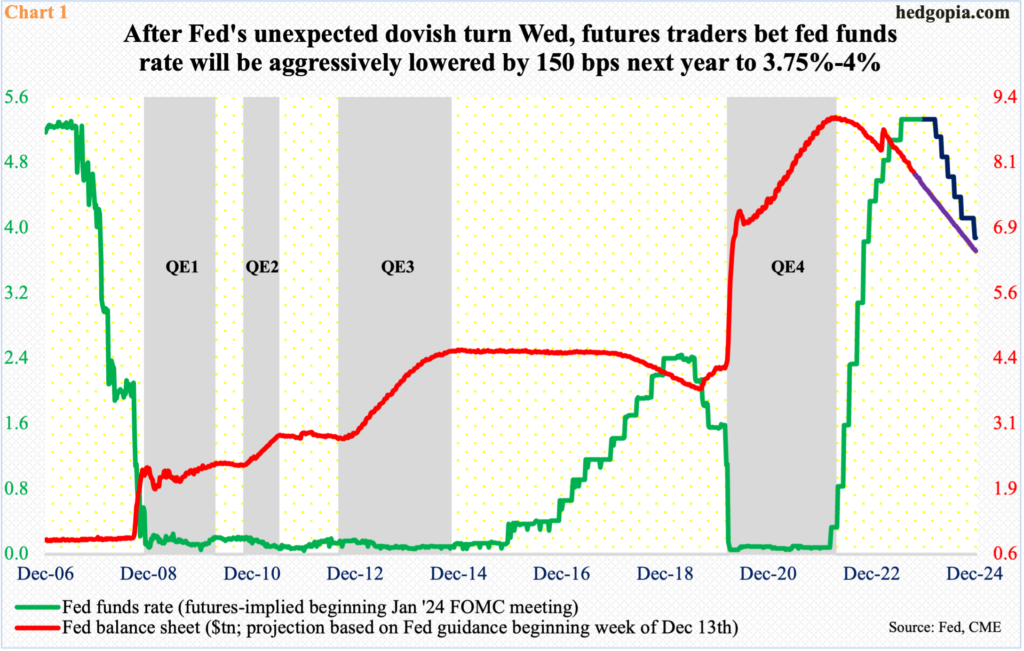

(The balance sheet continues to shrink – by about $95 billion a month. This will continue. At the current pace, it is on course to reaching $6.4 trillion by the end of next year, down from just under $9 trillion in April last year.)

What was not expected was the dovish message made by the FOMC statement and Powell later in the press conference. The dot plot is now leaning toward three 25-basis-point reductions next year, versus projections of two in the September meeting. Core inflation is expected to fall to 2.4 percent next year from this year’s 3.2 percent, while the unemployment rate is forecast to rise to 4.1 percent from this year’s 3.8 percent. GDP, in the meantime, is expected to decelerate from this year’s 2.6 percent to 1.4 percent next year, but no recession. A soft-landing nirvana, in other words!

Futures markets ran away with this outlook. Heading into the meeting, the traders expected four cuts next year, which was already much more than what the Fed indicated it was ready to give. Post-FOMC, they now expect the first cut to occur in March, followed by May, June, July, September and December, ending the year between 375 basis points and 400 basis points (Chart 1). Six 25-basis-point cuts to the tune of 150 basis points are priced in. They are obviously responding to a Fed that just made a sharp U-turn in its rates outlook for next year.

Powell until two weeks ago was sticking with his hawkish bias, highlighting the fact that inflation remains elevated and that the central bank would like to leave the rates high for longer. What changed? Between then and now, November’s consumer price index and producer price index came out this week – on Tuesday and Wednesday, in that order. Both were softer than markets expected.

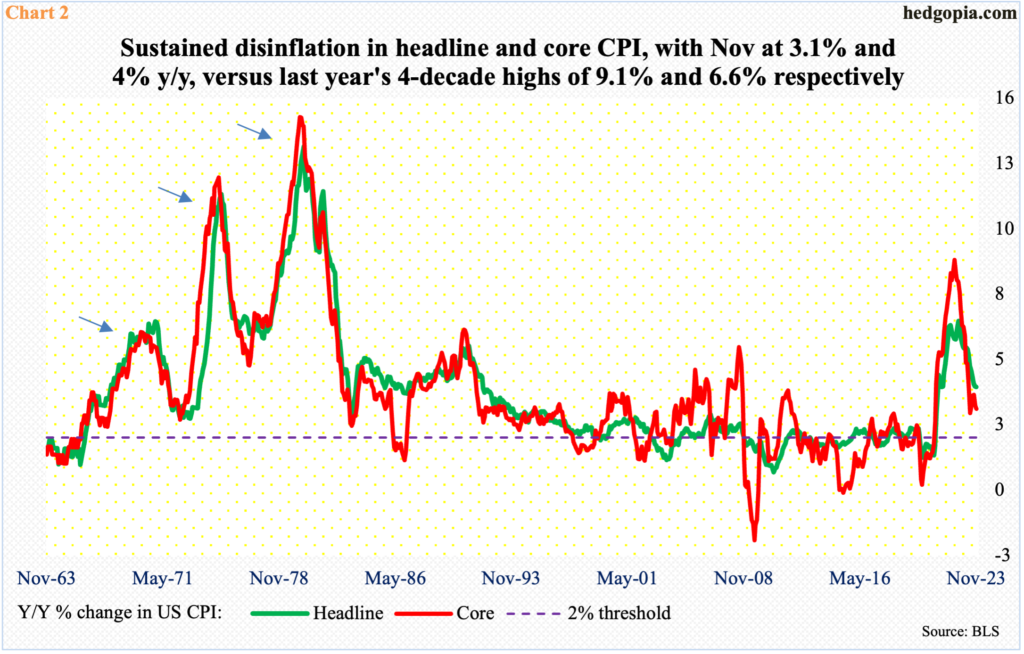

Consumer inflation no doubt is headed in the right direction.

In 2022, headline and core CPI were growing at an annual rate of 9.1 percent and 6.6 percent in June and September respectively. In the 12 months to last month, this had slowed to 3.1 percent and four percent respectively (Chart 2). The core is higher than the Fed’s targeted two percent, but core PCE (personal consumption expenditures), which is the Fed’s favorite, grew at an annual rate of 3.5 percent in October (November’s PCE is due out on the 22nd.)

As mentioned previously, the Fed expects the ongoing disinflationary trend to continue next year and beyond.

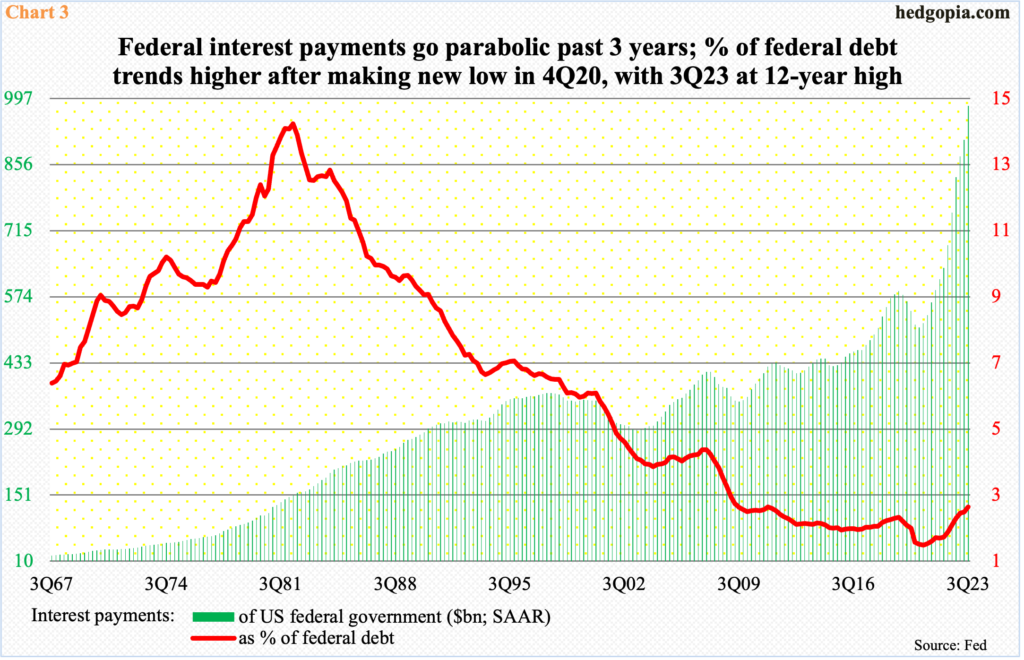

The other thing that probably contributed to forcing the Fed’s hands is the ballooning interest payments of the federal government. In the September quarter, these payments had surged to a record $981.2 billion (annualized). This was $508.5 billion 12 quarters ago. The soaring federal debt is the main culprit – $33.2 trillion in 3Q23 versus $26.9 trillion in 3Q20.

Rising rates do not help. Three years ago, rates were suppressed. Now, they are at multi-year highs. As a percentage of federal debt, interest payments made up 1.87 percent in 4Q20 – a record low. In 3Q23, this had risen to 2.96 percent, which is a 12-year high (Chart 3). For a debtor, the lower the rates, the better.

But all this does is just kick the can down the road. There is no fiscal discipline. The economy is on pace to grow well north of two percent this year, and the budget deficit in the 12 months to November stood at $1.74 trillion.

It is also possible the Fed now anticipates a sharp slowdown in economic activity in the quarters to come, in which case a little wealth effect would not hurt. Until recently, Powell did not seem to like the idea of a rally in equities because that would loosen the financial conditions, which in turn could potentially put inflation under upward pressure. This thesis has now been turned upside down, as he and his team knew the dovish turn would lit a fire under risk assets.

On Wednesday, the Russell 2000 small cap index shot up 3.5 percent and the Nasdaq 100 1.3 percent, with the S&P 500 large cap index up 1.4 percent. From the October 27th low, the S&P 500 is now up just under 15 percent. That is a lot of wealth creation in less than two months. In the meantime, the 10-year treasury yield gave back 17 basis points on Wednesday; from the October 23rd high of five percent, rates are down nearly a full percentage point.

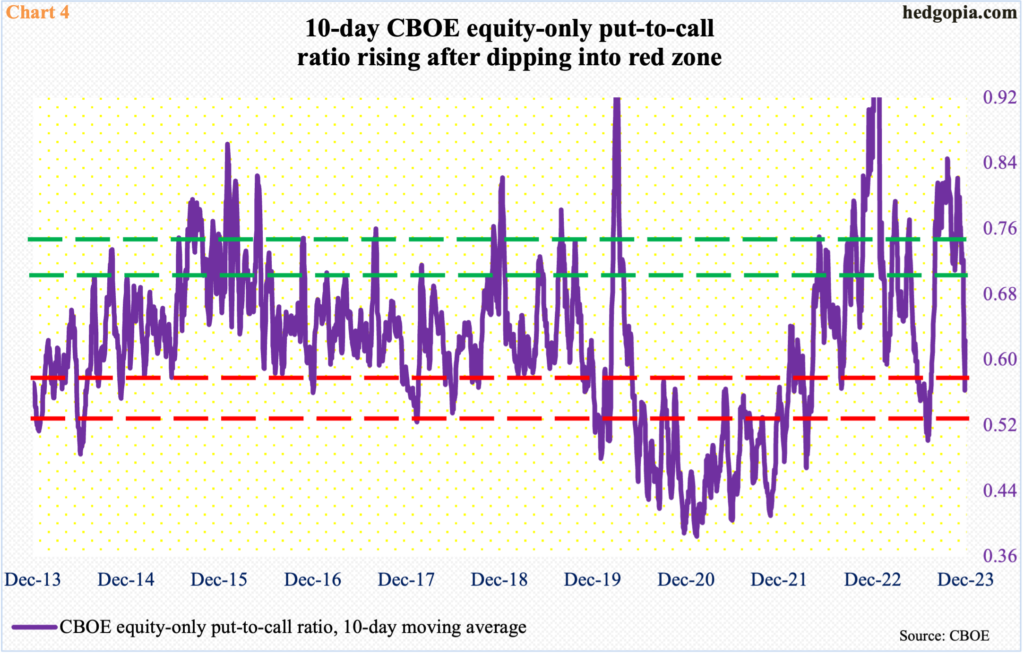

Animal spirits have been unleashed. The longer this sustains, the higher the chances of a buildup in excesses. Already, going into the meeting, the CBOE equity-only put-to-call ratio was in the 0.50s for eight sessions in a row, with the 10-day average at 0.563 – into the red zone (Chart 4). Oddly, despite the massive rally in equities, Wednesday produced a reading of 1.16, which helped push the 10-day ratio up. If past is prelude, unwinding will occur sooner or later. The longer the ratio remains in the red zone and equities stay firm, the resultant wealth effect has the potential to reignite inflation. This is the risk the Fed has decided to take on for now. The arrows in Chart 2 shows how consumer inflation experienced bouts of resurgence in the ’70s.

Thanks for reading!