The 10-year yield retreated last month from a potentially crucial spot. The supply-demand dynamics are in favor of bond bears, but this is also a well-known fact, hence may already be in the price. They at the same time are sitting on boatloads of shorts, facing squeeze risks.

The 10-year treasury yield failed an important test last month. In three of the four sessions through August 22, rates crossed 4.3 percent – both intraday and close – with an intraday tag of 4.36 percent on the 22nd.

Last October on the 13th, the 10-year hit 4.33 percent before coming under pressure, bottoming at 3.25 percent on April 6. The rally off of that low lost momentum as soon as the October high was reached.

Before meeting with downward pressure last October and August this year, the 10-year has had a phenomenal rally. As recently as this April, these notes yielded 3.25 percent – and 2.53 percent in August 2022 or 1.13 percent in July 2021.

Resistance at the October high also coincided with channel resistance. From the lows of last April-May, the 10-year has traded within a rising channel, the top end of which matched the October high (Chart 1). Channel support lies at four percent, or just north of it, with the 50-day moving average at 4.01 percent. Last Friday, yields dropped to 4.06 percent intraday before rallying to close at 4.17 percent. Once this support gives way, bond bulls (on price) could be eyeing 3.3 percent.

The weekly (on yields) is itching to go lower, even though the daily can rally here near term.

Fundamentally, from the perspective of supply-demand dynamics, bond bears cannot be blamed for arguing for higher yields. Because of higher interest rates, there has been a surge in federal interest payments, which went from a seasonally adjusted annual rate of $516 billion in 3Q20 to $929 billion in 1Q23. Concurrently, the Federal Reserve is reducing its balance sheet by running off its holdings of treasuries to the tune of up to $60 billion a month; the central bank currently holds $4.3 trillion in T-notes and bonds, versus a record $4.9 trillion held in April last year.

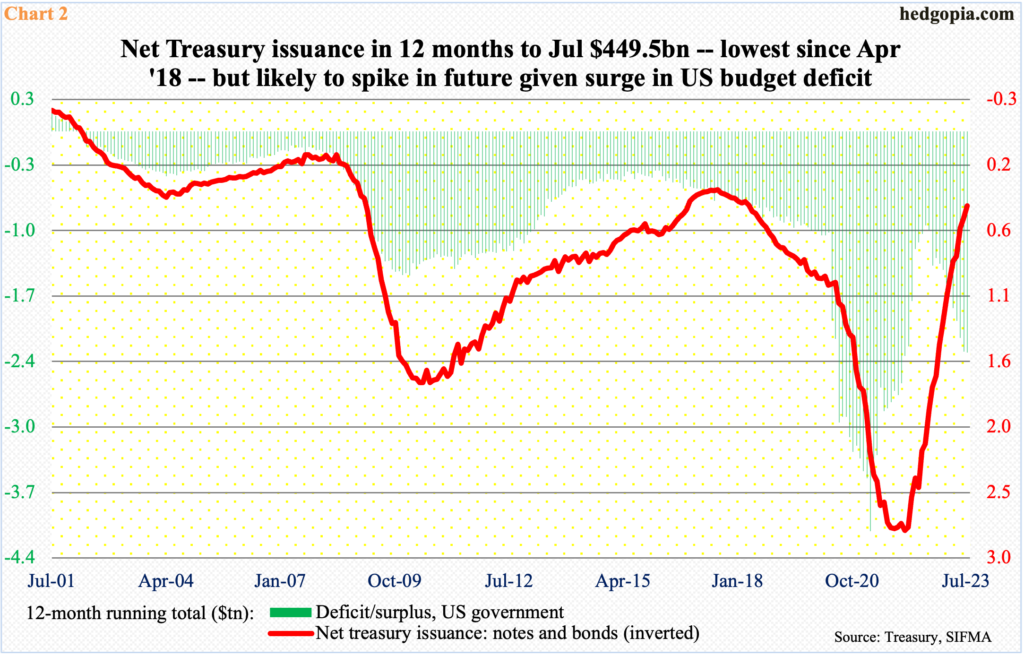

The US budget deficit has meaningfully gone up over the past year, with the 12-month total rising from $962 billion in July last year to $2.3 trillion this July, and the trend is expected to continue, as the red ink is being accumulated at a time when the economy is putting up decent growth numbers.

Treasury issuance, however, has been tepid. In the 12 months to July, net issuance of treasury notes and bonds was $450 billion, down from a record $2.8 trillion in January last year. This gap between the green bars and the red line in Chart 2 is destined to get filled by more issuance.

While announcing a larger-than-expected quarterly refunding auctions for longer-term securities, the US Treasury early last month stated that “while these changes will make substantial progress towards aligning auction sizes with intermediate- to long-term borrowing needs, further gradual increases will likely be necessary in future quarters.” Translation: expect a rise in issuance over coming months.

Interest rates have gone up big. In March last year, the fed funds rate was between zero and 25 basis points. This July, the benchmark rate was raised by 25 basis points to a range of 525 basis points to 550 basis points. The Fed is nearing the end of its tightening campaign; this has been one of the sharpest increases ever.

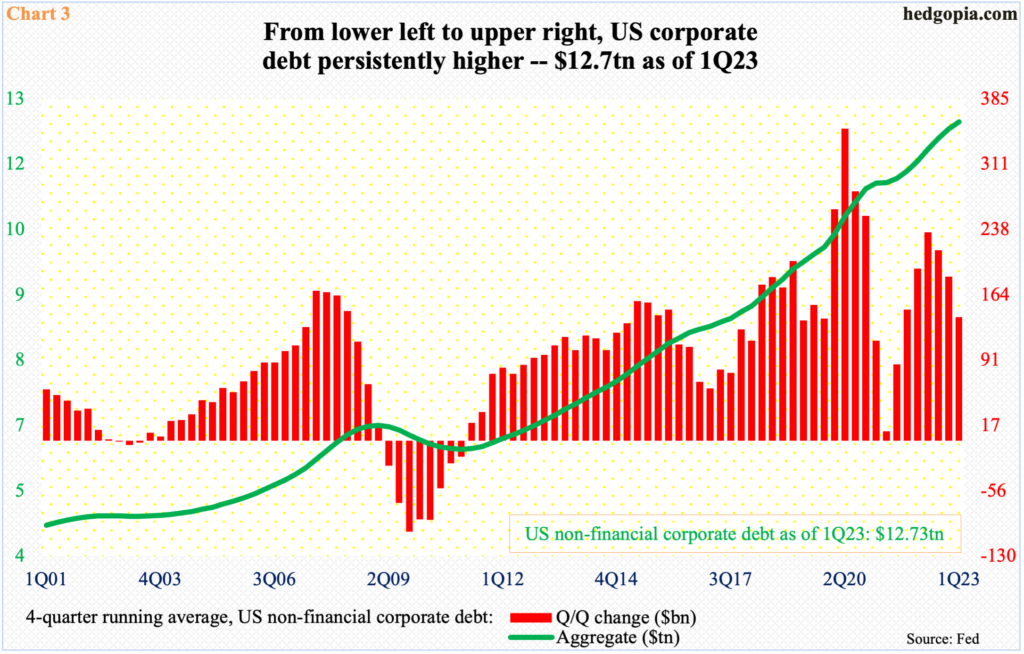

One of the areas higher rates will begin to adversely impact is corporate refinancing, which is expected to hit corporations hard next year, as they seek to refinance. US non-financial corporations are neck deep in debt.

As of 1Q23, these businesses owed $12.7 trillion – a record. (The Z.1 report for the June quarter is due out this Friday.) Chart 3 uses a four-quarter running average, and the trend has been nothing but up – from lower left to upper right. This was not much of a deal when interest rates were at/near record lows. Now that they have risen, refinancing will be done at much higher rates.

This in and of itself has the potential to slow down the economy, as corporations tighten their belts. This is just one of the many adverse impacts of the higher rates.

Late last year and early this year, many economists and equity strategists expected a recession to unfold this year. The economy, in contrast, held up very well, with real GDP growing at an annualized two percent and 2.1 percent respectively in the first two quarters this year. It is taking time for the higher rates to filter through to the nook and cranny of the economy. When contraction finally takes shape, this will now have come as a surprise, as the majority is not forecasting a recession.

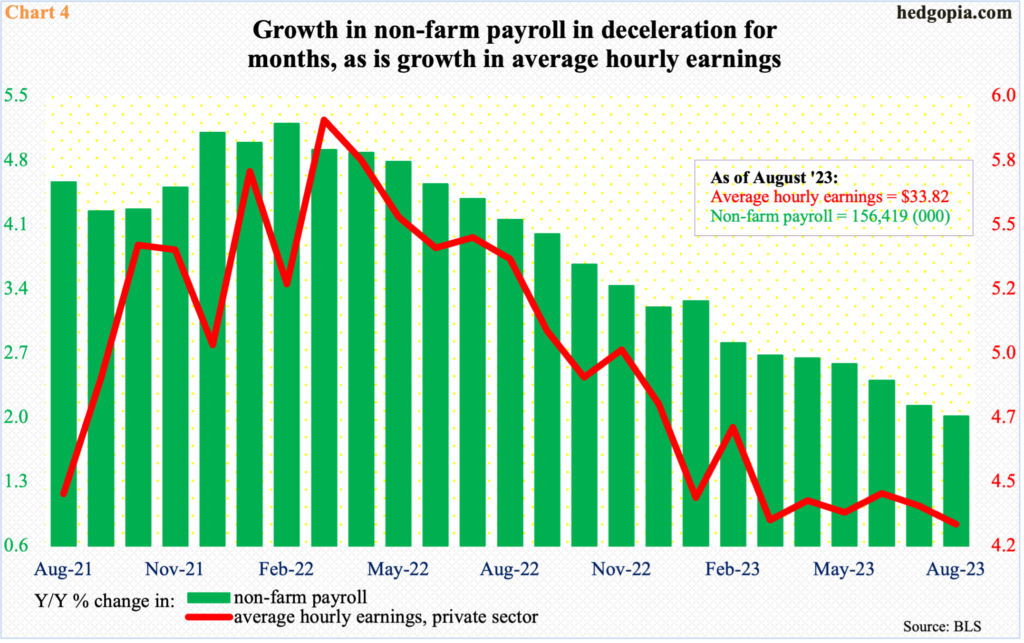

In fact, signs of deceleration in jobs are appearing – ranging from non-farm openings to unemployment claims to non-farm payrolls.

From a year ago, growth in non-farm jobs has decelerated for months, as has private-sector average hourly earnings (Chart 4).

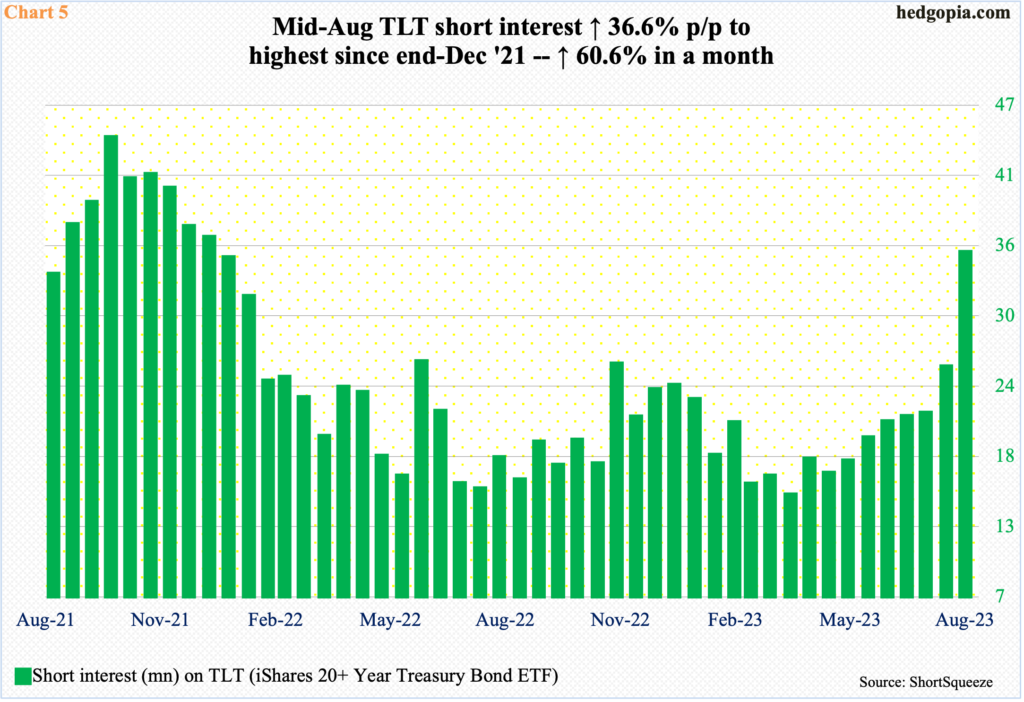

In this scenario, those betting on higher rates may very well be forced to rethink their thesis. The trade is crowded, to say the least.

As of the middle of August, short interest on TLT (iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF) rose 36.6 percent period-over-period to 34.7 million. Between mid-July and mid-August, it shot up 60.6 percent to the highest since end-December 2021 (Chart 5).

There is always a chance the trade gets even more crowded. Mid-October 2021, short interest stood at 44 million before heading lower; as these shorts covered, the 10-year yield dropped from 1.69 percent on October 22 to 1.34 percent on December 3 that same year.

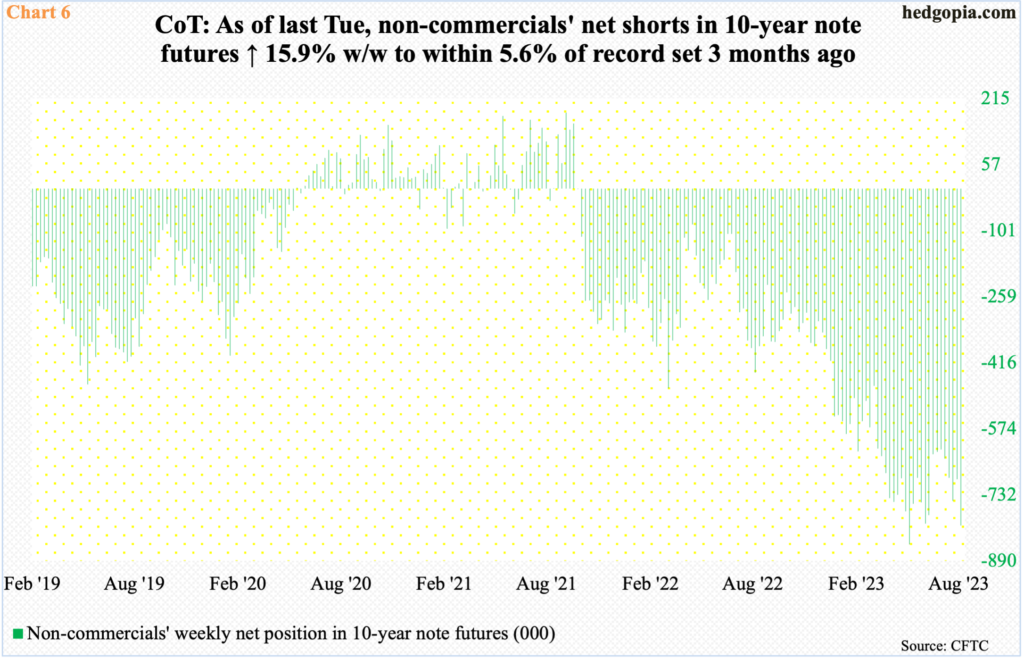

In the futures market, non-commercials similarly are stuffed in net shorts in 10-year note futures to the gills. In the latest week, which is as of last Tuesday, they held 805,553 contracts, which is merely 5.6 percent from the record high 850,421 registered in the week to May 30 this year (Chart 6).

Most recently, these traders have shown aggression since the week to July 25 when they held 623,771 net shorts; the 10-year yielded 3.91 percent in that session, subsequently rallying to the afore-mentioned 4.36 percent by August 22. So, in the aggregate, they have done well. But, since that high, rates have come down.

Non-commercials’ mettle will be tested once four percent is breached on the 10-year. Odds favor they will begin to cover/cash in profit once this unfolds.

Thanks for reading!