After rallies that lasted a little over two weeks, selling began on major US equity indices last week right at important resistance. This likely continues near term.

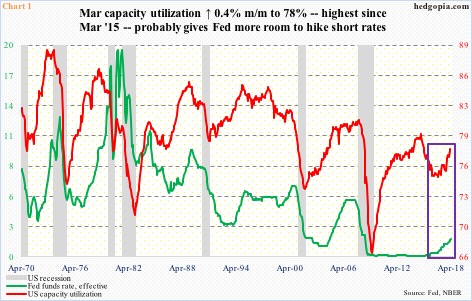

US capacity utilization in March rose 0.4 percent month-over-month and 3.3 percent year-over-year to 78 percent. In the current cycle, utilization peaked before reaching 80 at 79.6 percent in November 2014, and has risen since bottoming at 75 percent in November 2016 (Chart 1).

After leaving the fed funds rate near zero – between zero and 25 basis points – for seven long years, the Fed began hiking in December 2015. The second hike was one year after that. The rise in utilization, among others, gave the Fed ammo to raise four more times. Since December 2015, fed funds has gone up by 150 basis points, to a range of 150 to 175 basis points.

The FOMC’s dot plot from March foresees two more 25-basis-point hikes in the remaining six scheduled meetings this year. Thus far, capacity utilization is in agreement with this scenario – and reflected in two-year Treasury yields.

Two-year yields are seen as a proxy for monetary policy expectations. Last Friday, these notes were yielding 2.46 percent – the highest since August 2008.

In keeping with the rise in the fed funds rate, as well as future expectations, the rise in short rates has been quite steep. Not so in the long end. Ten-year yields (2.95 percent) have struggled to take out resistance at three percent. The last time they were above that threshold was in January 2004.

Consequently, the spread between the two has persistently shrunk. In December 2016, when the Fed hiked the second time, it stood at 134 basis points. In fact, as early as February 9, the spread was 78 basis points, which last Tuesday contracted to 41 basis points, with the week closing at 50 basis points.

If the Fed ends up moving two more times this year, the Fed funds rate would have risen to between 200 and 225 basis points. Assuming two-year yields keep up, the yield curve probably narrows further.

Historically, an inverted yield curve has preceded many of the US recessions (Chart 2). That said, except for the inability of the long end to keep up with the short end, markets are yet to genuinely fear contraction. This includes stocks.

US equities took a beating in February and March, but major support has not given way.

As a matter of fact, the Nasdaq 100, after the late January-early February selloff, even managed to rally to a new high in March, even as other major US equity indices were still below their respective late-January highs. The breakout did not last though, resulting in a bearish island reversal (box in Chart 3).

Last week, the index was rejected at short-term horizontal resistance, subsequently losing short-term trend line support. This can be viewed as a chink in tech’s armor. Nonetheless, during both February and early this month, the bulls defended the 200-day moving average. The 50-day was lost last Friday.

Last week also produced a gravestone doji. Near term, the path of least resistance is probably down. Ditto with small-caps.

In a shooting star session last Wednesday, the Russell 2000 small cap index got rejected at a falling trend line from the all-time high of 1615.52 on January 24. This was an ideal place for selling to begin, and that is exactly what happened. The index has had a nice rally since bottoming at 1482.90 on the 2nd this month.

But unlike the Nasdaq 100, the Russell 2000 has not yet lost trend line support from early this month. There is also horizontal support at 1550’s (Chart 4). Not to mention the 50-day, which is still 1.3 percent away. Besides the Nasdaq 100, both the S&P 500 large cap index and the Dow Industrials lost the 50-day last Friday.

Small-caps are leading their large-cap brethren – up 2.3 percent April-to-date versus up 1.1 percent for the S&P 500.

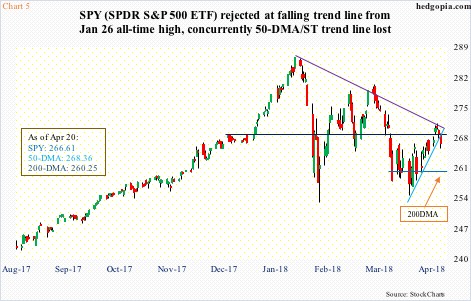

In the sessions ahead, the S&P 500/SPY (SPDR S&P 500 ETF) could very well continue to unwind their daily overbought conditions. In both February and March, selling stopped at/near the 200-day.

In other words, at least this week, SPY ($266.61) could very well be range-bound. A weekly short strangle can be used to take advantage of this.

Hypothetically, April 27 268 calls bring in $1.56 and 261 puts $0.65. The $2.21 premium is kept if the underlying ends the week between the strike prices. Breakeven is $270.21 and $258.79.

Risk is unlimited because both options are naked. With that said, as things stand, going long or short – if the need be – near the breakeven offers decent odds.

Thanks for reading!