The 10-year continues to perk up, eyeing 1.4 percent. The strength is seen even though the Fed continues to aggressively buy these securities, although foreigners have been cutting exposure. In a leveraged economy, higher rates will translate to higher interest payments, which in and of itself should act as automatic stabilizers.

The 10-year treasury yield has a spring in its step. Shortly after taking out one percent, which took place six weeks ago, it staged another mini breakout on Tuesday – this time out of 1.2 percent. With one session to go, rates are up nine basis points this week and were up as much as 13 basis points.

Earlier, after bottoming last March at 0.4 percent, the 10-year charted out higher lows, particularly so since August (Chart 1). The breakout six weeks ago completed an ascending triangle pattern. Slightly before that, yields reclaimed a falling trend line from November 2018.

Structurally, there is a lot for bond bears (on price) to like. Immediately ahead, there is decent resistance at 1.4 percent. On Wednesday, the 10-year (1.29 percent) tagged 1.33 percent intraday before retreating.

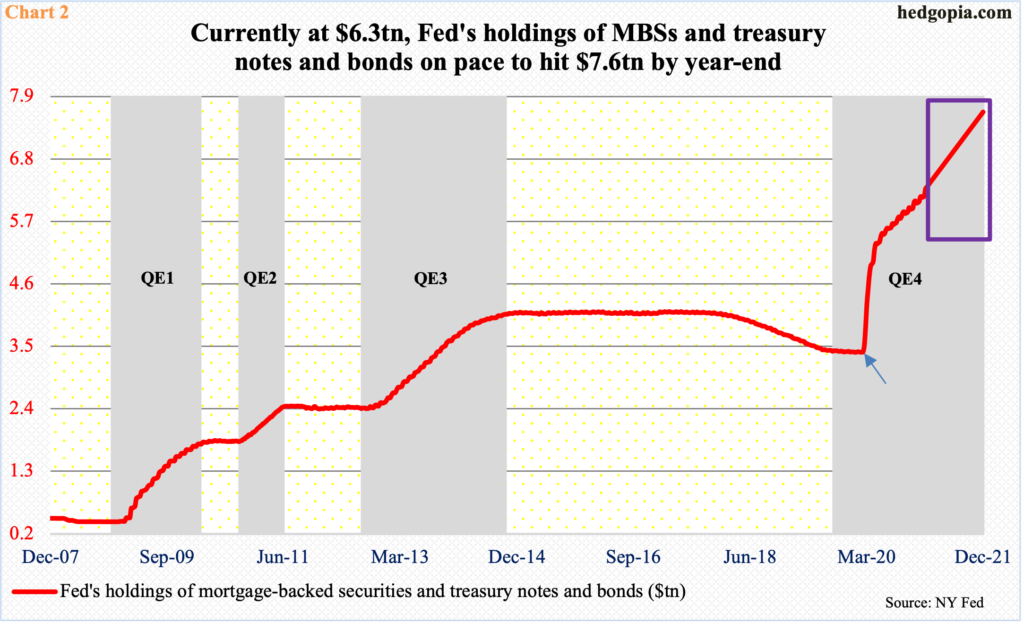

The 10-year has behaved this way in the face of all the purchases made by the Fed, which has said it would buy up to $120 billion/month in mortgage-backed securities and treasury notes and bonds.

As of Wednesday, the Fed held $2.16 trillion in MBSs and $4.11 trillion in treasury notes and bonds, up respectively from $1.37 trillion and $2.03 trillion in early March last year (arrow in Chart 2). On March 23 last year, the central bank announced unlimited QE.

At the current pace, the Fed is on pace to owning $7.62 trillion in MBSs and treasury notes and bonds by year-end (box), up from the current $6.27 trillion.

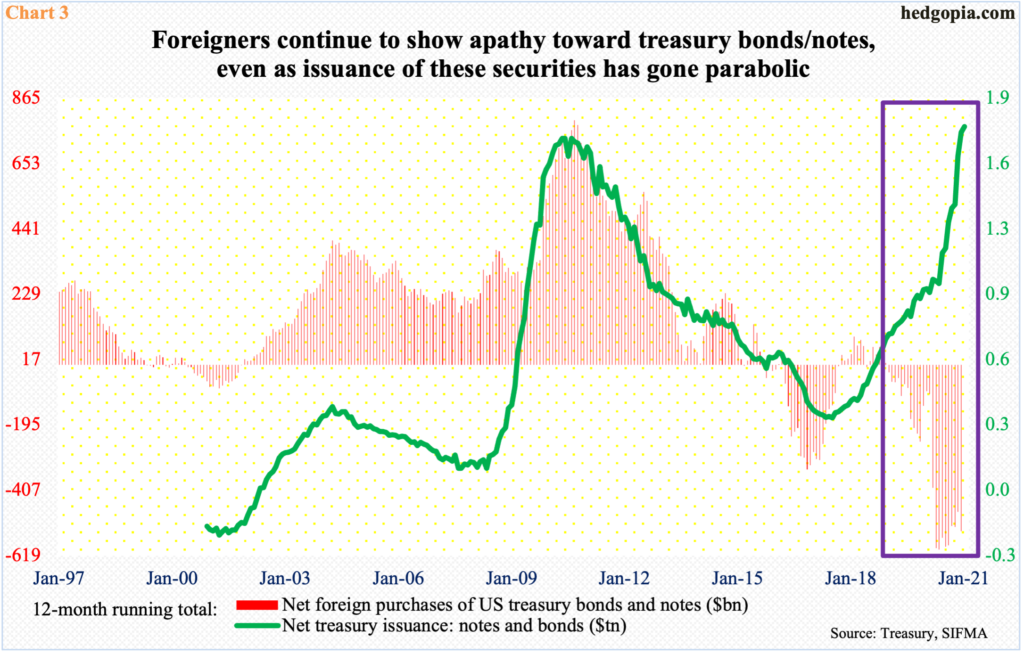

If not for all this buying, suffice to say that the 10-year yield would be much higher. Foreigners have already been reducing exposure to treasury notes and bonds.

Last December, they sold $20.7 billion worth. In all of last year, they cut holdings by $540 billion, versus sales of $133.5 billion in 2019.

Historically, foreigners’ purchases – or a lack thereof – moves hand in hand with issuance of treasury notes and bonds. The two have gone their separate ways the past two years (box in Chart 3).

Issuance has gone parabolic, particularly since last March, even as foreigners have been actively cutting exposure.

This raises the importance of Fed purchases even more.

Amidst all this, it is important to point out that the two-year yield needs a close watch as well.

Given the rise in the long end of the yield curve in recent weeks, everybody is wondering about the level on the 10-year that will begin to weigh on other assets such as equities and when the Fed begins to freak out. Is it 1.5 percent, two percent, or higher?

Because of the rally in the 10-year, the spread between yields on 10- and two-year notes has persistently gone up. Pre-pandemic, the spread was in mid- to high-teens. On Thursday, this was 1.17 percent. But the two-year refuses to budge (box in Chart 4).

Since last May, the two-year yield (0.11 percent) has been in low double digits to low teens. More often than not, these rates tend to move ahead of the Fed. Once that happens, the latter will acquiesce, and this should worry the markets a lot more.

But as things stand, the odds of that happening anytime soon are very slim. For that matter, the odds of the 10-year sustainably rallying higher are slim as well, as this will cause tons of hardship in an economy where leverage is very high – be it federal, corporate or household.

Thanks for reading!