“…the details of the tax legislation suggested that its effects on consumer and business spending – while still uncertain – might be a bit greater in the near term than they had previously thought. Although several saw increased upside risks to the near-term outlook for economic activity, members generally continued to judge the risks to that outlook as remaining roughly balanced.”

The above quote is from the minutes for the January 30-31 FOMC meeting released Wednesday. The members are downplaying the risks of an overheating economy.

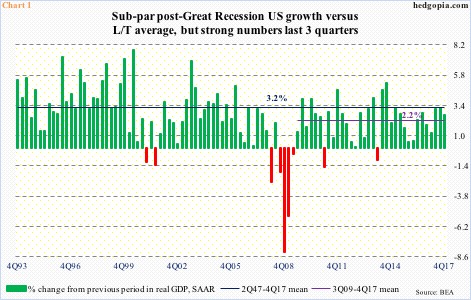

The rather sanguine statement follows very healthy growth in the U.S. economy in the last three quarters.

Real GDP expanded 2.6 percent in 4Q17 (first estimate), coming on the heels of growth of 3.2 percent in 3Q and 3.1 percent in 2Q (Chart 1). As of last Friday, the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model was forecasting another 3.2-percent growth in 1Q18.

The Fed remains accommodative. Now, there is fiscal stimulus. The above quote suggests as much. The recently enacted tax cuts are all but certain to entail higher budget deficit.

Yet, the Fed does not foresee growth acceleration.

At least two factors may be at play here.

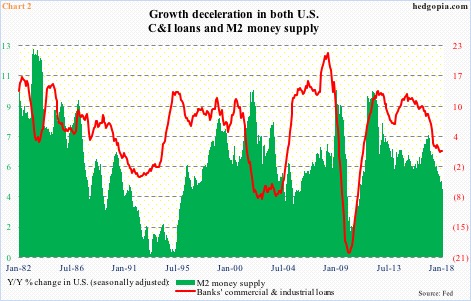

First is what is transpiring in the money supply.

Growth in M2 money supply has been decelerating since peaking at 7.5 percent year-over-year in October 2016. In January this year, it only grew at a 4.2-percent pace, to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of $13.8 trillion.

Concurrently, y/y growth in banks’ commercial & industrial loans slowed from 12.9 percent in January 2015 to 0.9 percent last November. January was up 1.2 percent, to $2.13 trillion (SAAR) – just about flat since last September.

This will obviously reverberate through the economy.

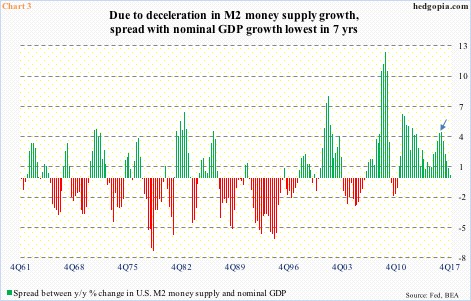

Speaking of which Chart 3 presents the spread between y/y percent change in M2 money supply and nominal GDP.

Most recently, the spread was 4.5 percent in 3Q16 (arrow in the chart), which then shrunk to mere 0.3 percent in 4Q17. This was all due to growth deceleration in M2, which went from 7.3 percent to 4.7 percent. During the period, growth in nominal GDP, in fact, accelerated – from 2.8 percent to 4.4 percent.

The trend in M2 is not going the right direction. Not to mention M2 money velocity, which in 4Q17 stood at 1.43, just a hair’s breadth above the all-time low 1.426 in 2Q17.

Second is what is going on in the interest rate front.

Historically, rates are low – across the yield curve. But of late, they have rallied massively. The rate for the 10-year Treasury note rose from 2.05 percent early September last year to 2.94 percent Wednesday, and two-year yields from 1.27 percent to 2.26 percent.

Particularly noteworthy is how 10-year yields are behaving. They are trying to cleanly break out of a three-decade-old descending channel. Yields have also broken out of a reverse-head-and-shoulders pattern, which, if genuine, could ultimately mean a move to 3.9 percent (Chart 4).

In a debt-laden economy – government, corporate and consumer – this kind of backup in yields sooner or later is bound to act as automatic brakes on economic activity. Mortgage applications are already dropping. This latest rise in mortgage rates is coming at the start of the spring buying season.

This is not a recipe for growth acceleration/overheating. The Fed knows this.

Thanks for reading!